|

|

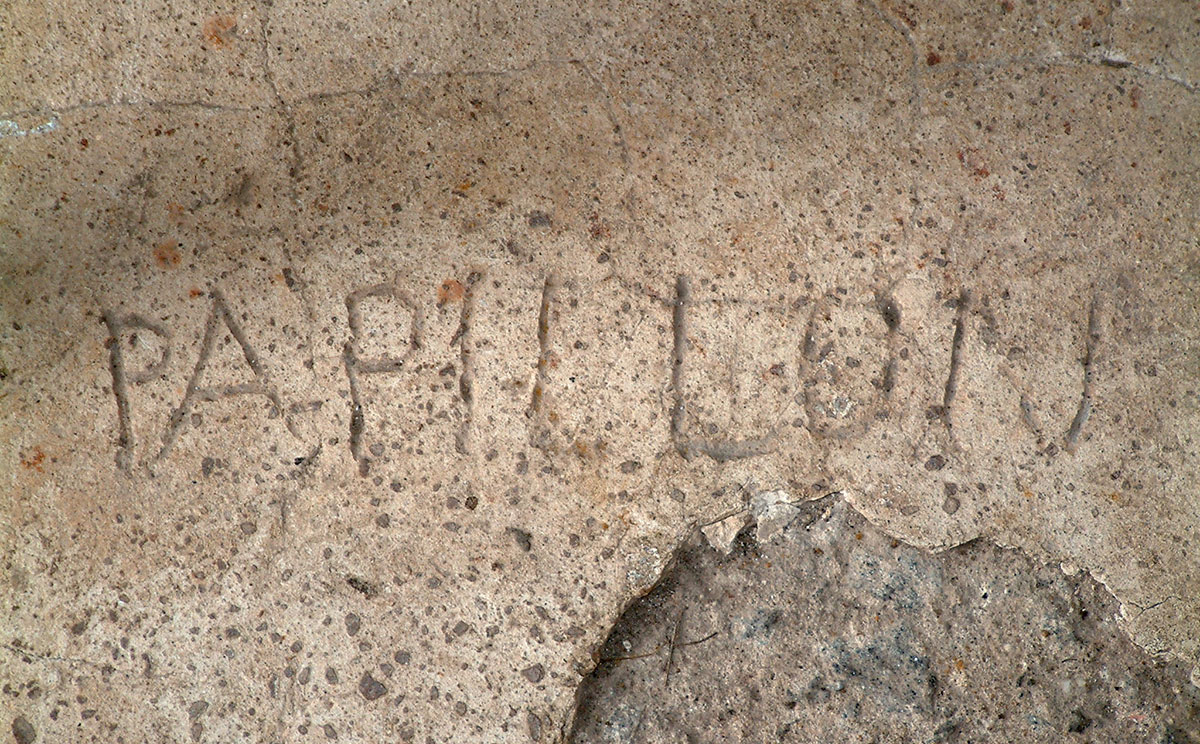

On the Trail of PapillonHow much truth was there to the prison escape story of Henri Charriere? Skeptoid Podcast #848  by Brian Dunning The 1973 movie Papillon told the story of a French petty criminal, framed for murder and condemned to a life sentence of hard labor in the infamous penal colony of French Guiana. The movie was released hot on the heels of its source material, the autobiographical book of the same name, by Henri Charrière, whose tattoo of a butterfly on his chest gave his story its title. Charrière had lived the incredible tale of hardship, death, disappointment, and escape in that prison colony, and eventually made his way back to civilization and to France. His book sales rapidly brought him fame and fortune such as he had never known, but not everyone was so enamored. A few journalists were skeptical, and their own books soon followed: books which claimed fatal flaws in Charrière's narrative, and charged him with fabrication. Today we're going to look at these claims, and at Charrière's own; and see if we can dig through this story of high adventure and find that line that separates fact from fiction. When the movie came out in the United States in 1973, there was already quite a bit of controversy surrounding it — though this had mostly been known to the French-speaking audience and American audiences were scarcely aware of it. The story's flamboyant author and hero, Henri Charrière himself (who had served on the film crew as a technical advisor) probably attracted more media attention than the movie's stars, Steve McQueen and Dustin Hoffman. Charrière was in every production still, was interviewed in every Hollywood magazine, and was about town as a celebrity. Though he spoke with scorn of the claims that his story was fabricated, it appeared that he relished the extra attention. However he felt, he certainly seemed to enjoy the spotlight, no matter the intent behind its gaze. The movie was a commercial success, though not an especially explosive one; but beyond the numbers, it failed to impress. Critics consistently found it boring. It was lumbering, it lacked passion, it wasted the talents of its two superstars. But half a century after its lackluster release, Papillon has achieved cult classic status among many. It's definitely on my list of favorites, but whether it belongs on yours is up to you. Charrière's undisputed history began in Venezuela in the 1940s, where he landed after escaping French Guiana. He was taken into custody and held under brutal conditions at a prison called El Dorado for a year, but fate was on his side. In 1945, a Democratic coup d'état swept Venezuela, resulting in the replacement of all personnel at the prison. Having no papers or proof of any sentence, Charrière was freed and allowed to become a resident of Venezuela, and ultimately a citizen. He lived in Caracas for more than twenty years as a restaurateur, marrying and raising a daughter. Then in 1968, earthquake damage to his restaurant inspired him to look for a new source of income, and he decided to write Papillon. Over three months, he filled 13 children's ruled notebooks with handwriting. He sent it to a publisher in Paris. It hit the bookshelves in 1969 and its sales were an overnight success. In France, its first edition sold 1.5 million copies. It was translated into English for the United Kingdom market in 1970 by the novelist Patrick O'Brian, and into every other major language as well. Papillon became the all-time bestselling book in Europe. Due to the book's extreme popularity and Charrière's claims of innocence therein, France pardoned Charrière's murder conviction in 1970, clearing the way for him to legally return to Paris, a newly minted millionaire. He began a lucrative acting career, writing and starring in a movie called Popsy Pop about a jewel thief, and his publisher squeezed a Papillon sequel out of him called Banco. Almost immediately, two books came out in French claiming to have thoroughly debunked the Papillon story, both written by investigative journalists who were skeptical of the tale. The first, Les Quatre Vérités de Papillon ("The Four Truths of Papillon"), was by Paris Match reporter Georges Ménager, and studied Charrière's life in Paris before his conviction, and found that he had badly misrepresented himself. While Charrière claimed to have been a small-time thief and safecracker, court records showed that he was in fact a police informant who made his living pimping out his wife. For the second book, Papillon Épinglé ("Butterfly Pinned"), journalist Gérard de Villiers actually traveled to French Guiana and examined prison records and interviewed other prisoners and former guards, and found that virtually nothing Charrière had claimed was true. Far from being a serial escape artist, hell-bent on getting out at all costs, Charrière had a relatively clean record showing only a single unauthorized absence in 11 years. Perhaps the most dramatic location in the book was Devil's Island, one of a tight group of three tiny islands just off the coast, said to be where the worst of the worst prisoners were sent: the most violent, or the most likely to attempt escape. In the book's climax, Charrière escaped Devil's Island by tossing a bag of coconuts off the island's tall cliffs, then using them as a raft to float back to the mainland from where he eventually made his way to Venezuela. Only, prison records showed that no Henri Charrière had ever been sent to Devil's Island. Why would he? Devil's Island was for political prisoners only, supposedly to prevent them from spreading subversive propaganda. Of 70,000 prisoners sent to the colony, only about 50 were ever sent to Devil's Island. No murderers like Charrière were among them. Anyway the islands have no tall cliffs; they are small and low lying, and their rocky shores slope gently down to the water. Charrière would have known these facts. He did spend two years on one of the other islands, St. Joseph, close enough to Devil's Island that one could easily swim back and forth. He was there to serve a two-year solitary confinement sentence for his one documented escape attempt. Unlike the brutal conditions depicted in his book, prisoners were allowed out every day for exercise, including being allowed to swim. Moreover, De Villiers found that apart from Charrière making the one attempt that landed him on St. Joseph, he was otherwise something of a model prisoner. He was content in his job cleaning out latrines at the main prison facility in town, Saint Laurent, and never caused any trouble. According to other books written by former prisoners, such as 1988's dramatically titled Devil's Island: Colony of the Damned and 1961's Flag on Devil's Island, most jobs at Saint Laurent were pretty relaxed — one author's job was as a portrait painter for the guards and their families. Many non-troublesome prisoners came and went freely, working at menial jobs in town; after all, the purpose of the prison was to transition prisoners into colonists. De Villiers also learned that some of the stories in the book did happen, but that Charrière had not been involved in them. These included the murder of a former convict who had turned manhunter; a mass prison break called the Cannibals' Break because the escaping men killed and ate one of their own; and a case where Charrière supposedly saved a guard's daughter from a shark attack at the beach on St. Joseph. That did happen, but the prisoner actually responsible was attacked himself, losing one or both legs, and died soon after. Then, in the 1990s, the original publisher of Papillon, Robert Laffont, dropped something of a bombshell in an interview. When Charrière first submitted his handwritten manuscript for publication, he presented it as a fictional novel. It was Laffont who had persuaded Charrière to call it an autobiography, a story they both stuck to until Charrière died in 1973. More trouble for Charrière's story came out in 2005, when a 104-year-old decorated World War I hero named Charles Brunier went public with the claims he'd been making for years that much of Charrière's story was based on him. Brunier, who had a butterfly tattoo on his left arm, said it was he who had been nicknamed Papillon, not Charrière; and that much of the book had been lifted from stories he had told Charrière in the 1930s. Was either man's story true? It's virtually impossible to verify. But we do know that pretty much anytime something like this hits pop culture, there are always people who "come forward" out of the woodwork, claiming to have had some important role in the story. Brunier presented no evidence other than his word. So, who knows. So how did Charrière get to Venezuela? Of course no honest account survives, so we don't know any details; but De Villiers, based on his travels to French Guiana and the interviews he conducted there, pieced together a probable scenario. At the time that France fell to the Nazis, French Guiana declared allegiance to Vichy, and Surinam — directly across the river from Saint Laurent — was controlled by the Allies, and ceased cooperating with the prison and stopped returning escaped prisoners. Charrière probably did what a lot of the guys did: simply walked away from his job in town and hired a boat to row him across the river. Once in Surinam, he had a relatively free road to Venezuela — no dramatic high adventures needed. And luckily, the Venezuelan coup that resulted in his official freedom and citizenship was just around the corner. So have we shattered anyone's illusions, and taken away a favorite story? Well, I certainly hope not, because that would be a negative process. Instead we've just replaced one story with another, and both are equally filled with conflicts, just of a different kind. Moreover, one is true while the other is not; so really, I think this has been a net positive. You can still enjoy the movie — it's not like "based on a true story" has ever been remotely true in movies. And now you have another story, that actually is true, to enjoy on top of it. So enjoy your fiction, and enjoy your facts... just don't get them confused.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |