|

|

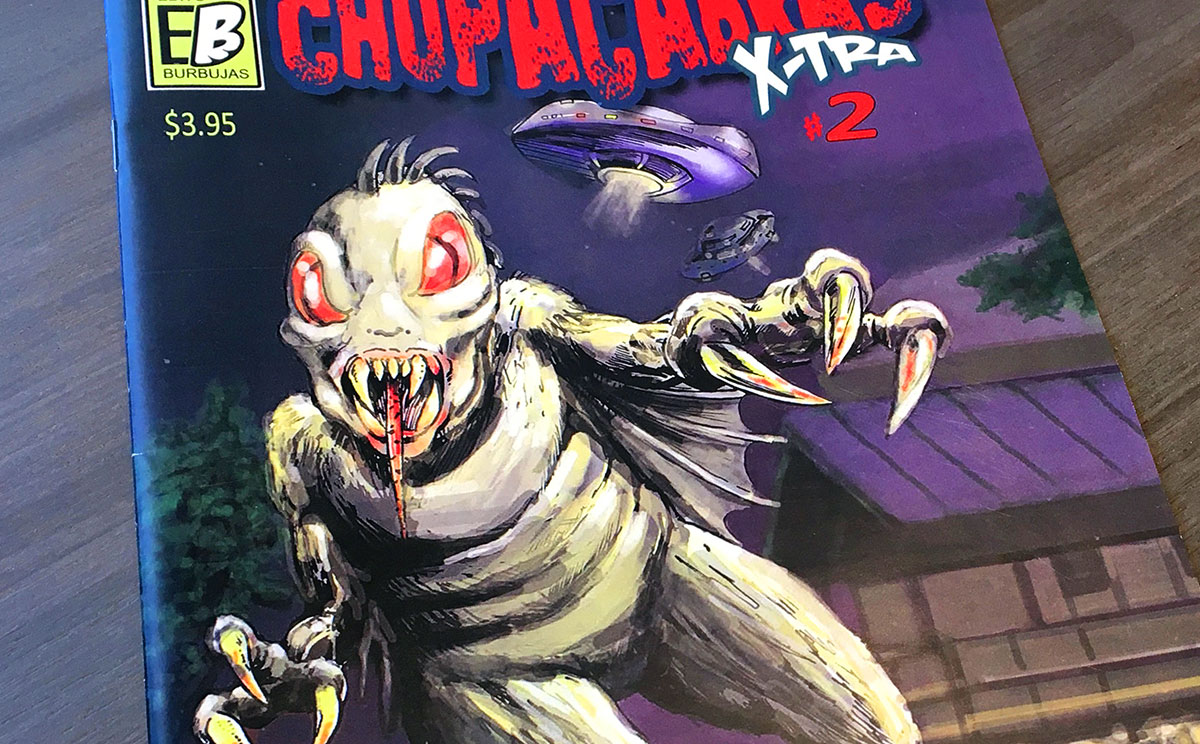

On the Trail of the ChupacabraSkeptoid Podcast #815  by Brian Dunning Today we're going to track down an infamous monster, the chupacabra. It is said to take any of several forms, but always that it sucks the blood of its prey, often livestock, leaving a drained carcass with surgically neat puncture holes. It's been reported all around the world, and in various centuries; and so taken in the aggregate, one might reasonably assume that there is sufficient evidence to declare it a real creature. But whether that creature is physical, or a phantom, or an alien, or purely folkloric is a more complicated declaration to make. Today we're going to gather all that evidence, shine the light of science and reason on it, and see what we can say for certain (if anything) about this legendary beast. The chupacabra earned its named only as recently as 1995 following widely publicized news reports of cattle mutilations in two small Puerto Rican towns, Orocovis and Morovis. The reports were fairly conventional, following the same pattern of most cattle mutilations in the news. This happens every so often all around the world, and I've written on it before. What happens is nearly always the same: a rancher finds dead livestock: cows, goats, whatever, with specific parts of their body neatly excised with no apparent blood spilled and no obvious sign of predation, and then it's always reported that it was done by Satanic cults or aliens. There's no need to go into this in depth, but science has had the complete explanation for cattle mutilation for a long time. The animal dies for whatever reason, and then very quickly (a matter of hours) certain birds and/or insects will attack its exposed soft tissues: eyes, mouth, genitals. As the animal is dead there is zero blood pressure and thus no blood, making it seem like the animal has been drained of blood. The dead skin pulls tight from the excised area, giving the impression of a surgically cut line. There is a complete Skeptoid episode on cattle mutilation, #456, if you want all the details. It can look very strange, so ranchers and reporters can be forgiven for jumping to oddball conclusions. All of these things happened following the incidents in Puerto Rico in 1995. Police sought the Satanic cults, UFOlogists looked for the aliens, and comedians leveraged the colorful events for new material. One of these, radio personality Silverio Pérez, is generally believed to be the first to put the Spanish words for suck and goat together and called it the chupacabra. (Sometimes it's written with the plural for goats, chupacabras; but as it's a made-up word either is equally correct, and the singular chupacabra seems to be most common.) Some credit others with coming up with the name first, and some researchers have found one or two earlier appearances of the compound word in the world's literature; but 1995 in Puerto Rico is the first time the word was used as the name of a vampirical livestock-killing monster. So for some five months, the chupacabra was really only known in Puerto Rico, and then only really in the domain of UFOlogists, vampire believers, and other fringe theorists. The few initial cattle mutilations had been the extent of the phenomenon, and it likely would have died out like all the world's other countless cattle mutilation cases. But then came the event that made the chupacabra immortal. Madelyne Tolentino lived with her mother in Canóvanas, a municipality on the east end of Puerto Rico's biggest city, San Juan, and some 54 kilometers east of where the cattle mutilations had taken place. Her mother woke her from a nap one afternoon and took her to the front window where a strange creature was hopping about in the yard. It was some three feet tall (usually misreported as four to five feet tall) with wrinkly gray skin like wet leather with short fur. Its arms and legs were thin and each had three very long digits; its face was flat with slanted wraparound eyes. It hopped like a kangaroo. Most notably, it had a line of long, thin spikes running down its back. Tolentino was persuaded it was the chupacabra, and the story was reported. A sketch was made and widely circulated. The story was all over the news. The mayor of Canóvanas vowed to protect the public from the menace. Tolentino's basic description has informed much of chupacabra lore ever since. And while many chupacabra reports have followed that model, many more have not. Most chupacabras sighted in later years (especially in the United States) were more like canines, and have been adequately explained as dogs, coyotes, or foxes with mange, explaining their strange, hairless, emaciated appearance. Others point to vampire stories from throughout the Americas as evidence that the chupacabra predates the Puerto Rico cattle mutilations, such as the Moca vampire from 1975 in Puerto Rico (a giant winged and feathered creature), or the Nicaragua beast of 2000, shot by a rancher who caught it attacking his goats, and it turned out to be an ordinary dog. There are countless such stories from the Americas since 1995, all attributed to the chupacabra. Every one that has been identified has turned out to be a dog, a coyote, a raccoon, or — in a particularly head-scratching case — the odd-looking carcass of a skate, a type of ray from the ocean. Why have all these obviously unrelated incidents been called chupacabra attacks? The answer is what cryptozoologists Loren Coleman and Patrick Huyghe called the Lumping Problem. This is when people throw a single name at what may be many unrelated creatures or phenomena. To use their example, they express frustration when people attach the name Bigfoot to reports of creatures from all around the world that may have different colors, behaviors, sizes — creatures that they believe may be zoologically distinct and deserving of individualized investigation. But you don't have to be a cryptozoologist to recognize the difficulties that the Lumping Problem introduces. Here on Skeptoid, the Lumping Problem has been responsible for people taking many different irreconcilable phenomena and calling them all ball lightning, or many unrelated phenomena in the sky during earthquakes and calling them all earthquake lights. When Madelyne Tolentino saw her spiky alien creature in Canóvanas, why was it blamed for the cattle mutilations on other parts of the island? Canóvanas is nowhere near the two towns where the cattle mutilations were reported. One thing had absolutely nothing to do with the other. Tolentino reported that her creature was basically just hopping around in her mother's yard in an urban residential neighborhood; it wasn't attacking any animals, drinking anyone's blood, or behaving in any threatening way at all. What evidence linked the creature to the livestock deaths? If you hear that a jewelry store was robbed in another city, and then five months later you happen to see an unusual-looking person on the street in your own town, you don't instantly charge that person with the robbery. As there is no evidence linking one thing to the other, we have nothing to investigate; but we can still present a confident theory. Our human brains do this all the time. A brain's whole job is to link things together, to recognize things, to match one thing to another. When we hear a strange thing was done by an unknown agent, and then we see a very strange agent, boom; our brain makes the connection. Even though there were countless thousands of human beings closer to the mutilated cattle, all of whom are far more physically capable of harming livestock than Tolentino's small thin creature would be, the creature was strange, and the mutilations were strange, and that's all it takes for our brains' automatic pattern matching to render a verdict. However, in this particular case, we have two reasons to go further than merely exonerating the creature from any bloodsucking activities. First, as already discussed, it is virtually certain that there was no attacking entity involved in the cattle deaths. We have no crime with which to charge Tolentino's creature. And second, we have sufficient reason to dismiss Tolentino's account completely. This became public in 2011 with the publication of Tracking the Chupacabra by Benjamin Radford of the Squaring the Strange podcast. Tracking the Chupacabra was the first scholarly book purely dedicated to an exhaustive investigation of the entire chupacabra phenomenon: the vampire phenomenon as a whole, the many sightings and reports of chupacabras from around the world, and importantly, a deep dive into its most important story points. The most astounding of Radford's many discoveries was that Madelyne Tolentino had (perhaps unintentionally) already thoroughly debunked her own story, in a 1996 interview for UFO Digest. A couple of weeks before Tolentino's alleged sighting of the creature in her mother's yard, the movie Species was released in San Juan. It's about a creature — which matches the description of Tolentino's chupacabra right down to the spikes — created in a Puerto Rican laboratory by government scientists using alien DNA, which escapes and goes around killing people. Tolentino told them what she'd seen in the movie, and that an unnamed journalist told her those alien-hybrid creatures who escaped from the government lab lived in nearby El Yunque National Forest. The interview makes it apparent that Tolentino knew the movie was just a movie, but that she also believed its setting was completely real — that a government laboratory in Puerto Rico creates alien-hybrid creatures which can sometimes escape. Following his own interview with Tolentino, Radford wrote:

Again, this all came directly from Tolentino herself. She saw Species, believed it was a fact that alien hybrid creatures like the one in the film were running about loose in her area; it should be little wonder that her personal description of such a creature matched the one in the movie, feature for feature. But even beyond that, we have good reason to doubt that she ever had any such sighting at all. She told Radford that she encountered it on a second occasion in December 1995, which seems highly dubious; and her husband, Miguel Agosto, interrupted the UFO Digest interview to assert that he'd once watched a chupacabra fight with a dog; and that during the struggle, the chupacabra managed to shave clean a patch on the dog before biting it there. That both Tolentino and her husband sat there with a straight face and related these fantastic episodes to the UFO reporter should cast grave doubt upon their credibility. Today, decades after the fact, few in Puerto Rico think about, care about, or even remember the chupacabra kerfuffle from 1995 — especially since a long series of hurricanes have given them existent things to worry about. When taken as a whole, the entire chupacabra phenomenon consists of little more than three things: some conventional cattle mutilations which are neither rare nor unexplained; a bit of fan fiction from a couple who enjoyed the movie Species; and then a raft of inappropriately lumped-in reports from all over, of mangey dogs and coyotes or just about any strange sighting or unidentified animal. But as far as there being any evidence for an alien-like being going around and sucking the blood of livestock, you have very good reason to be skeptical.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |