|

|

On the Trail of the YowieAustralia's version of Bigfoot may -- or may not -- have its origin in Aboriginal mythology. Skeptoid Podcast #762  by Brian Dunning It is said to be Australia's version of Bigfoot or the Yeti. It is said to be well known to the Aboriginal people. Stories in the English language literature from Australia go back hundreds of years, as early settlers reported encounters with strange creatures. Today we're going to have a look at the Yowie and see if we can find a real animal hidden among all these diverse tales. It's a journey that's going to take us back into the past and even along a brief detour through modern UFO mythology. And by the end of it, we'll either know the truth or we won't; a result which is in itself a fair metaphor for this elusive beastie. Here is just a single sampling. In 1876, the Australian Town and Country Journal reported the following harrowing tale:

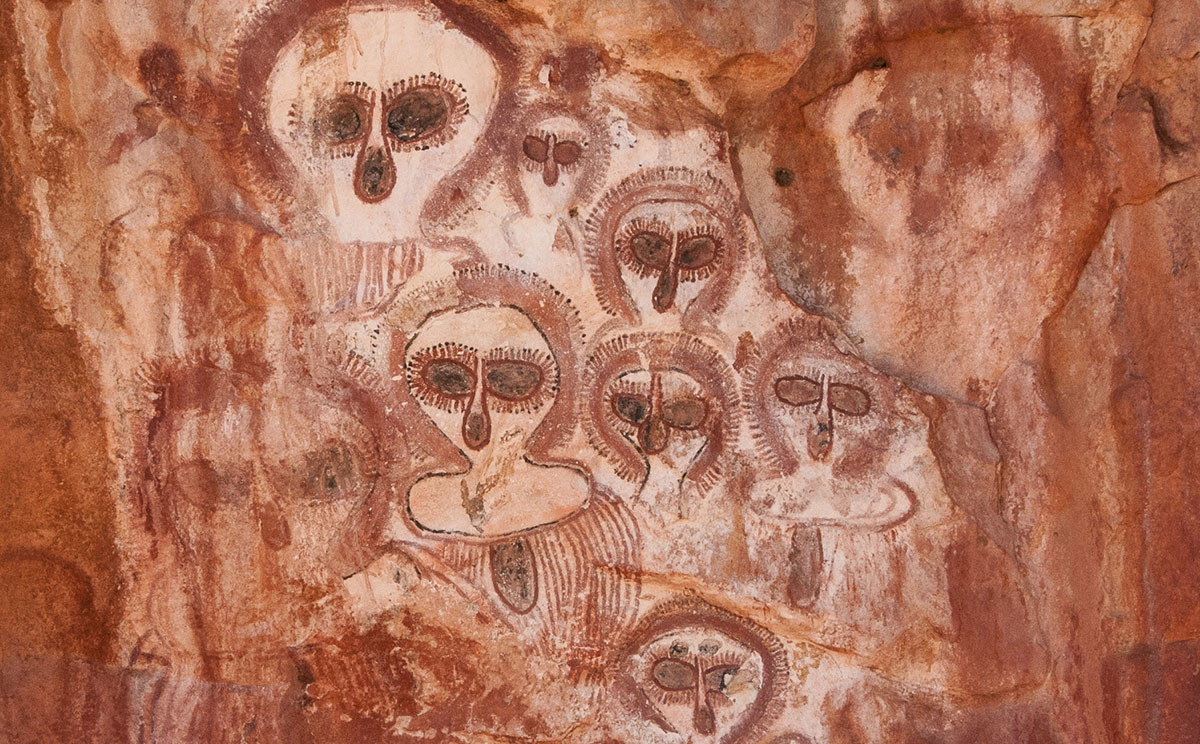

Today, the Yowie exists in the realms of cryptozoology. Its believers treat it as a real, yet undiscovered, animal; very similar to how Bigfoot advocates take their charge completely seriously as a legitimate creature. Also just like many of the Bigfoot believers, Yowie believers turn immediately to Gigantopithecus, the extinct Pleistocene ape from southeastern Asia, as the probable identification. Reports of Yowie sightings are sent to the cryptozoology website editors just as often as are Bigfoot sightings; and blurry, shaky, unidentifiable videos of supposed encounters are posted to YouTube at about the same frequency. Both cryptids are represented by exactly zero evidence; neither exists in any fossil record where it necessarily would if it did exist; neither is taken seriously by more than one or two legitimately credentialed primatologists in the relevant field; both are represented by a range of physical descriptions that are so divergent that they cannot possibly represent any one actual animal; and both are claimed to live in a range of ecological systems diverse enough that no actual animal would be adapted well enough to survive in all of them. But their most intriguing similarity is that both sets of believers go to great lengths to tie their beliefs to local ancient legend. Because while it's easy and gratifying to poke fun at those crazy country yokels who believe in the stupid cryptid, nobody wants to give the traditional legends of indigenous people that same treatment. We tend to regard native legends with reverence and respect; and when we can tether our cryptid beliefs to these revered traditions, we do so in the hope that the perception of legitimacy and substance will stick to them. So while Bigfoot hunters in North America point to strange faces on totem poles and dig through Native American storybooks to find mystical sounding words like wendigo which they can frame as a sort of bastardized heritage for Bigfoot, the same appropriation has been taking place halfway around the world in Australia. To understand how this happened, let's begin by turning back the clock about 50 years. In 1972, one of the early books about the American Bigfoot and the Nepalese Yeti was published and received reviews in the press in Sydney, Australia. Among those reading these with great interest was the paranormalist and prominent Australian UFO author Rex Gilroy. Turning to Aboriginal mythology, Gilroy identified a creature called a Tjangara, and declared that Bigfoot was found in Australia as well as the United States and Nepal, to much press coverage. Gilroy and his wife Heather dubbed themselves the "Australasian Cryptozoological Research Centre", and then set about hunting for parallels between their Australian Bigfoot and creatures from Aboriginal mythology. The results of this effort were summarized in Gary Opit's self-published 2009 book on the Yowie:

There are over 300 Australian Aboriginal languages from at least 28 language families. How many mystical creatures would be found in the cultural legends of all those different languages? I doubt anyone has ever even tried to estimate that; but it has to be an enormous number. The idea that all of those different names we just listed would all be referring to the same creature, found throughout the continent, strains both philological and anthropological credibility. That paragraph is not evidence that a single physical creature was well known by many names throughout the many cultures that make up the Aboriginal world; it is evidence that cryptozoologists have collected as many old legends as they can in an effort to bolster their belief by claiming, without evidence or credibility, that those legends all match their particular creature. If a comprehensive study in comparative mythology was done among all those languages — which, given how many of those languages are nearly dead, is likely impossible — chances are slim that a creature would emerge that is consistently described continent wide. Those minority of the folkloric creatures for which a uniform physical description even exists differ profoundly from the Bigfoot-style creature described today. So, in short, no — the fact that there are many Aboriginal legends does not support the existence of a Yowie. In fact, that they clearly do not describe today's version of the Yowie can be viewed as evidence against its existence. But that's a point that hardly needs to be made. That a Bigfoot-style creature currently does not rampage across Australia should be our default starting assumption and is hardly an interesting revelation. What is interesting, and also useful to know, are the reasons that the belief exists. And this brings us to Graham Joyner, who in the 1970s was an archivist in Canberra and amateur historian. Joyner had been doing his own deep dive into the historical literature, particularly the old newspaper reports of encounters. Following the popularity of the articles by Rex Gilroy, Joyner decided to compile what he'd learned into a book that, he felt, set the record a little more straight. This book, 1977's The Hairy Man of South Eastern Australia, has since become one of the primary sources for the true history of the Yowie legend. The book includes 29 early print references to a beast called a Yahoo, dated from 1842 to 1935. Joyner knew that Jonathan Swift's 1726 satirical novel Gulliver's Travels introduced the word yahoo as a term for a coarse or brutish person. In the book, Gulliver traveled to four different fanciful islands, and in the fourth he encountered the Yahoos, a race of filthy brutes who resembled (but were not) human beings. The book turning out to be quite popular, it was therefore not surprising that when showmen began touring about England and Australia showing off a captured orangutan or some other great ape beginning in the early 1800s, they called it a Yahoo. Thus, among 19th century Australians, yahoo became the de facto common English word for an apelike wild man. There was no pretense that it had any Aboriginal roots, at least not at first. However, in the 1970s, the enthusiasts in an Australian Bigfoot — notably the UFOlogist Gilroy — combed through the Aboriginal literature and found words close enough that Gilroy could declare the Aboriginal Yowie was the same animal as Joyner's Yahoo. Yowie happened to be the word that resonated with Australia's popular media; and so all the sightings since the 1970s have been Yowie sightings, while all those early ones that Joyner found referred to the Yahoo. It should be pointed out that this version of the Yowie's history does appear to be the prevailing one, but it's not universal. The Bigfoot believer community tends to reject the idea that the introduction of the English word yahoo played any role and that yowie did indeed descend from Aboriginal folklore, and this view has bled over into a fringe of the scholarly community. I include this in acknowledgement of the fact that the complete history of the Yowie legend is not known for a certainty, though among the most rigorous researchers, the backwards grafting of Gulliver's Yahoos onto the sideshow orangutans and thence to the similarly named creatures from Aboriginal mythology does seem to be what best fits the whole history. And if we can take that as the probable story, we once again conclude a Skeptoid examination not with a boorish debunking and certainly not with a credulous confirmation, but rather with something richer than either. We have an understanding and an appreciation for the cultural currents that create legends, giving them a context and a meaning that is far more interesting, useful, and relevant, than a mere campfire story of a monster in the Outback.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |