|

|

Who Sank the Maine?Skeptoid Podcast #748  by Brian Dunning It was just before 10pm on February 15, 1898, when a blazing orange reflection turned the waters of Havana Harbor to fire. The double thuds of massive explosions thundered throughout the city, and voices all along the shoreline screamed as a yellow fireball, dotted with countless shards of debris, billowed skyward. Below it, the battleship USS Maine, fatally sundered, slid into the black water. Even as the first bodies slapped into the bay, people began debating what had happened. And, for more than a century since, few can agree on what sank the Maine, plunging two great superpowers into the Spanish-American war. We'll begin with a quick summary for those of you either not from Spain or the United States, or who simply need a refresher on the Spanish-American War. In the late 1890s, Cubans were engaged in their third rebellion against Spain, which had long claimed Cuba as a territory. Only 150 km away, the United States watched closely: its Monroe Doctrine dictated that they resist any European nations seeking to expand into the Americas. The USS Maine's job was to intimidate Spain, and so it rode at anchor in Havana harbor. US public opinion was strong against Spain. The American press reported that Spain was inflicting all manner of atrocities against Cubans — the reports were exaggerated, but it was what the American public was hungry for. For its part, Spain was no great fan of the US flexing its mighty war muscles all around what was — by the standards of the day — legally their territory. The Maine mysteriously exploded and sank in February 1898, killing 260 American sailors. The United States considered that an attack by Spain, and so they declared war. Cuba was not the only territory that the United States wanted to expel Spain from; these also included the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico. The Spanish American War was fought for 10 weeks in all four places, both at land and at sea, including Teddy Roosevelt's famous charge up San Juan Hill in Cuba with his Rough Riders. Spain got the worst of the war and was first to negotiate for peace, which was achieved through the US making a large cash purchase of infrastructure and Spain vacating all those territories. With all of that having been at stake, it's easy to see that there were pretty good justifications for virtually everyone to want to blow up the Maine. And accordingly, virtually everyone has been accused of being the responsible party. In no particular order, here are the nominees:

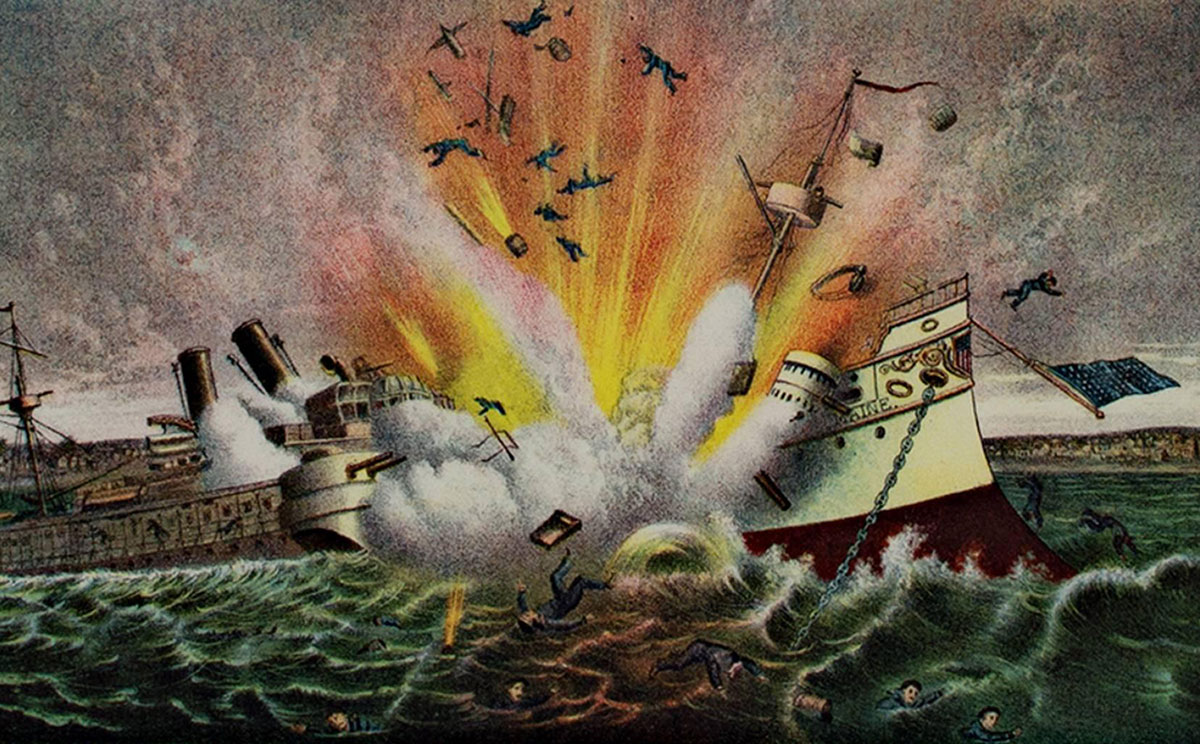

As far as what the investigations revealed, most of them — by the Cubans and the Spanish (remember the sinking happened before there were declared hostilities) and by the Americans — all found that nominee #5, a coal fire igniting the ship's magazine, was the true culprit. These included the 1898 Spanish inquiry and the 1974 Rickover investigation when the US Navy wanted another look using modern forensics. The exceptions were the 1898 Sampson Board and the 1911 Vreeland Board, conducted when the wreck of the ship was raised. Both of these found that an external explosion is what had caused the powder magazine to detonate, destroying the ship. No assignment of blame was made as there was no evidence. But with the exception of those two, no other investigation has ever supported that finding. So let us now look more closely about what's actually known about each of these nominees. The Americans Did It ThemselvesQuite obviously, a false flag attack against their own ship to fire up support for going to war with Spain is the overwhelmingly preferred hypothesis among conspiracy theorists. And in Cuba, it remains the official narrative. Initially, Cuba and Spain both accepted the finding that it was an accident; but once Fidel Castro came to power and the Cold War of propaganda dominated relations between the US and Cuba, Castro wholeheartedly embraced the idea of a US false flag attack, and that's what you'll find in Cuban history books today. That the Americans would have done this in order to seize control of Cuba, as Castro said, can easily be dismissed in light of the simple fact that they did not do so. They did go to war with Spain and easily defeated them, and could have even more easily defeated Cuba, but they didn't. The Monroe Doctrine was simply to keep Europeans out of the Americas, there was no charge to seize colonies of its own — as we can see from history that they did not do so. That the Americans would have done this for humanitarian reasons to help the poor Cubans is equally illogical. American public opinion was already virulently against Spain. Nobody needed convincing. The most famous painting of the explosion of the Maine, made in 1898 by Kurz & Allison for the popular press and widely reproduced and copied, graphically depicts American servicemen being hurled aloft in the blast, floating dead in the water, and shows the American flag toppling overboard. Its reflection of the popular sentiment is clear. The American public was frothing at the mouth for war with Spain. The American government had invoked the Monroe Doctrine before, and could have easily done so again without sacrificing one of their top warships at a time and place in which it would have been needed the most. The Spanish Did ItThe obvious implied accusation made by the Sampson Board, which found a mine was responsible, is that it was a Spanish mine. But Spain was far from eager to go to war against the United States. Spain was already struggling in its war against the Cuban insurrection and was seeking a peaceful resolution; the last thing in the world they'd have wanted would have been to provoke the United States into attacking them. There was, however, a group of far-right, ultra-nationalist radicals within the ranks of the Spanish military called the Weylerites, named after a brutal Spanish general nicknamed The Butcher. Weylerites once passed a threatening note to the Maine's officers when they were ashore, and there had been occasional reports of specific Weylerite threats against the Maine and other targets. But none of these ever came true, and as a marginalized fringe group within the Spanish military, the Weylerites had very little influence on actual operations. The Cubans Did ItCuban rebels were really the only group that had anything to gain from sinking the Maine. Their insurrection was going quite well, and if they could get the Americans to enter the war on their side against Spain, victory would have been easy (and this is in fact exactly what happened). If they could have sank the Maine, they knew the Americans would blame the Spanish (and that, too, is exactly what ultimately happened). Some Cubans, though, worried that the Americans would be just another imperialist occupier; so the desire to see them enter the conflict was by no means universal. So it's not surprising that no evidence has ever surfaced of a Cuban plot to sink the Maine. It is, however, the only conspiracy theory that has a logical rationale. American Newspapers Did It to Create NewsAny written history of the Spanish-American war goes to great lengths to detail the "yellow journalism" that characterized that period in the American press. The term — which has innocent origins in a yellow-shirted cartoon character — was emblematic of the battle between Joseph Pulitzer's New York World and William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal. They were the National Enquirers of their day, sensationalizing whatever news they could and making up whatever they couldn't. Both papers latched onto the existing American passions against Spain and fanned the flames to sell more papers, with stories such as those exaggerating Spanish mistreatment of Cubans. Conspiracy theorists are quick to charge that a newspaperman would finance a commando raid against a warship, but that doesn't answer the question of how that would have benefitted their particular newspaper at the expense of the others. The sinking and subsequent war were reported in all the papers, not just the one that allegedly organized the sabotage. The Coal FireAnd so, with little rationality behind any of the conspiracy theories, and no evidence, we're left with what has been concluded by most investigations: a coal fire that ignited the Maine's powder magazine. This is something that happened to coal-powered ships, and the Maine had a coal bunker separated from its forward magazine by only one thin steel bulkhead. Survivors did not report any coal fires and none set off the Maine's thermally activated fire alarms, but such fires often smoldered deep within the coal and could have gone undetected. As we know from episode #615 on Titanic myths, the Titanic had at least one such fire burning for the duration of its one voyage, and there were more than 20 such fires reported on US warships during the decade of the Maine's destruction. Divers did go down after the 1898 sinking to examine the wreckage hoping to find a cause, but of course there's very little they were able to see, and no engineers or experts were present. From what little they had to work with, they concluded that a mine had been placed on the hull near frame 18. It was the Vreeland Board investigation in 1911 that had direct access to all the physical evidence. As the wreck was a hazard in Havana harbor, a cofferdam was built around it and the site was pumped dry in order to facilitate moving it, allowing engineers direct unfettered access to the entire wreck. The Vreeland Board's conclusion was that it had indeed been an external explosion that set off the magazine, but further aft than the Sampson Board's frame 18. This conclusion was supported by hull plates that had been bent inward, consistent with an external explosion according to the Vreeland engineers; but not necessarily to Rickover's 1974 engineers. A series of two explosions was also consistent with what witnesses had reported in 1898, consistent with both a mine and then the magazine, or an explosion in one magazine and then another. The wreck was cut up and towed out to the deep, making any further investigation virtually useless. Noting that in 1898 and 1911 it was common for the US Navy to find causes for incidents that did not reflect poorly upon the Navy, a 2009 report from the Law Library of Congress found that no one explanation could be firmly supported. The early conclusions of a mine may have been biased, but nothing from the modern era could rule them out. The final word is that we don't know what triggered the Maine's magazines and sank it. Insufficient evidence survived for the limited forensic technology of the day to make a definite determination, and even less survives today. Both an accident and an act of sabotage are consistent with all that we know of the sinking of the USS Maine. And so, rather than make some presumptuous assertion that we cannot adequately support, instead we will take a moment to remember the 260 sailors, all valuable human beings who would rather have been someplace else on that dreadful night. Correction: An earlier version of this incorrectly stated that the Maine was dazzle painted; inconsequential, but wrong nevertheless. It also wrongly asserted that a US false flag attack was the official narrative in Spain, which is clearly contradicted by references from over a century of Spanish textbooks. —BD

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |