|

|

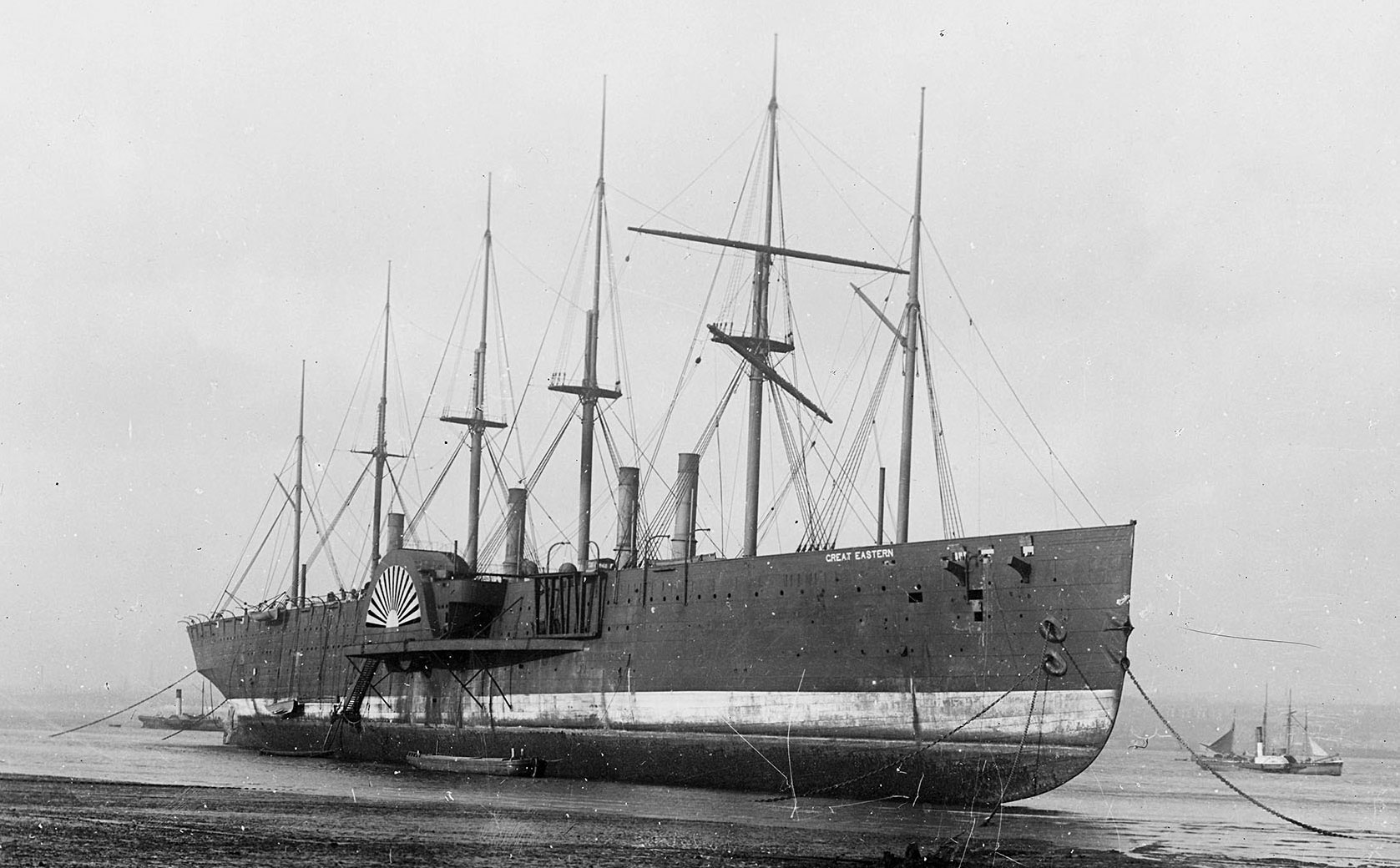

The Skeletons of the Great EasternSkeptoid Podcast #730  by Brian Dunning There is an old story, which you've certainly heard in one form or another, about an unfortunate riveter who found himself sealed inside the hull of a ship under construction, only to be finally released decades later when the ship gets broken up for scrap. His skeletonized remains spilled out before the surprised workers. In some versions it's one skeleton, sometimes two. Often this story is misattributed to a more famous ship like the Titanic, but the origin of the tale actually comes from a ship that's perhaps less famous, but is one of the most important ships in the history of ship building: the Great Eastern. Launched in 1858, she was, at 211 meters, by far the largest ship in the world; by volume, eight times larger than any other. Of the many stories associated with the Great Eastern, it is that of the two unfortunate riveters and their lonesome skeletons found more than 30 years after their entombment, where we will point the skeptical eye today. This story is particularly close to my heart; I first read about it as a boy in the National Geographic volume Men, Ships, and the Sea, which I read and re-read dozens of times:

Today it's a favorite yarn that I share with my own kids. And it's certainly easy to find; it's included in not only every book or website about the Great Eastern, but also in virtually any collection of nautical ghost stories. The Great Eastern was the brainchild of the renowned British engineer, the magnificently named Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Designed to carry 4,000 passengers in incomparable luxury, the Great Eastern was so large that no one nautical technology of the day could propel it; so it was fitted with the largest single propeller yet built driven by six enormous boilers; the two largest paddlewheels yet built turned by the largest oscillating cylinder steam engines ever built; and six(!) masts that carried enough sail to completely cover an entire football field. It was not exceeded in length for 41 years, by the liner RMS Oceanic, which still couldn't match the Great Eastern's gross tonnage. Sadly the marvelous ship became known for an unlucky career. She lost money throughout her lifetime, had several tragic and expensive accidents, and never came close to selling out all her staterooms. She once struck and sank another ship with the loss of 22 lives, and in 1862 she grounded on a rock off Montauk, NY, ripping a 30m gash in her outer hull that laid her up for three months — a repair which spawned jokes about workers trapped between her double hulls. After an inglorious career laying trans-Atlantic cables, Great Eastern was next reduced to a floating advertising billboard, and was finally broken up for scrap, which took three years beginning in 1889. The popular legend is that all her troubles were due to the curse of the two unfortunate riveters trapped within her iron depths. The first thing I searched for was newspaper articles from that time and place. This yielded nothing at all, but given the scarcity of searchable archives, could not be considered even close to conclusive. I did find a number of references to an article in Scientific American Supplements; as its name suggests, a supplementary publication to the famous magazine. It was published in November 1891, after the completion of the demolition. It discussed the ship's unique design, gave its history including its misfortunes, and listed out the recovered value of its resulting scrap. On the subject of deaths associated with the great ship, it said:

If Scientific American were to have mentioned the discovery of riveters' skeletons, you'd think this is where they'd have put it. But they didn't. The article did detail many of the deaths resulting from her other misfortunes, but not all of them. So this detailed and reliable reference turned out to be of no value to our investigation. Although no mention of the skeletons has turned up in news sources of the day, books (and modern web articles) are full of them. In particular, many give this same quote. It's from the 1953 book The Great Iron Ship, by James Dugan, all about the life of the Great Eastern. In his chapter on its demolition, Dugan wrote:

Sourced from Dugan, the text of Duff's letter has since been included in virtually every nonfiction book that mentions the Great Eastern. I find it in The Golden Age of Steam (1967), Circuits in the Sea (2004), Seven Wonders of the Industrial World (2012), The Mammoth Book of Unexplained Phenomena (2013), The Leviathan (2019), and others. Simultaneously, we find efforts to debunk the story of the two skeletons. It being impossible to prove a negative, these efforts generally center on the implausibility. Most focus on the fact that there were open access hatches, well known to the builders who built them:

Others mention that that's not the way riveters work, that both a riveter and his basher wouldn't both be on the same side of the hull. Good speculation, but certainly not proof. However, in Patrick Beaver's 1969 pictorial history of the Great Eastern called The Big Ship, we get the first indication that such proof may in fact exist:

The author referred to was Lionel Thomas Caswall Rolt, a biographer of prominent English engineers with a reputation for meticulous detail. The research Beaver referred to can be found in Rolt's 1957 book Isambard Kingdom Brunel: A Biography. He devoted one full page to a thorough disproving of the skeleton story:

And sure enough, a review of various published histories of the Great Eastern does indeed corroborate that the spaces between her hulls were thoroughly inspected at least three times and probably more: once after her disastrous 3-month ordeal of being launched, again after an 1858 boiler explosion, again during the 1859 fitting out Rolt referred to, and almost certainly a fourth time during the 1862 repairs of the ruptured outer hull. No skeletons were reported on any of these occasions. The earliest print reference does seem to be Dugan's 1953 book in which he gives the often-repeated quote, the snippet of a letter written to him by a certain David Duff. Who was this mysterious Duff? Although he was later a wartime tug captain, at the time the Great Eastern was being broken up he was a young cabin boy aboard a local tug. Was Duff a mischievous boy who invented the whole thing? Probably not, as the story of workers trapped inside the hull had been around since at least the ship's 1862 grounding. The young Duff could well have heard the skeleton rumor from the same grapevine of maritime gossip referred to by Rolt. And so we have no need to close this episode with a poignant plea for these phantom phantoms to finally take their well-earned rest. The skeletons of the Great Eastern, as illustrious and fun though the idea may be, never existed. It is the ship itself — with its matchless galleries, promenades, and power plants — that was the true wonder; no added fictional elements needed to make it one of our greatest tales of the sea.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |