|

|

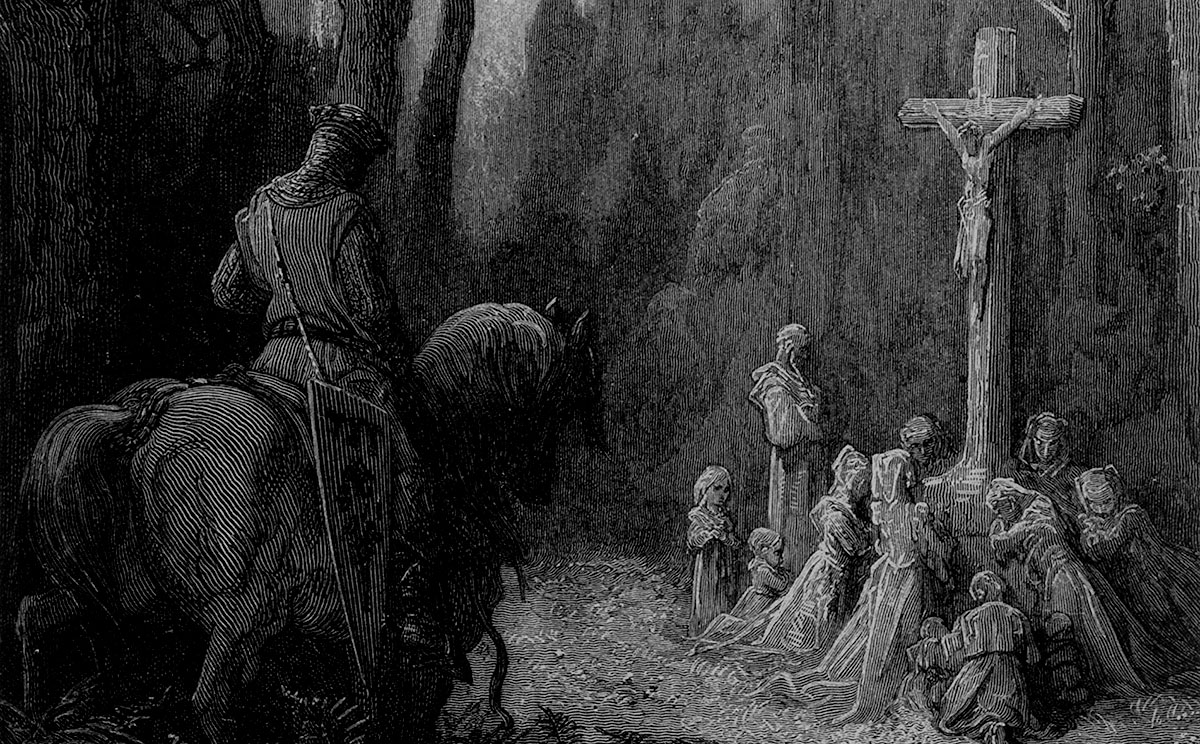

Draining the Holy GrailThe true history of the Holy Grail, the most precious of all artifacts. Skeptoid Podcast #723  by Brian Dunning Regardless of whether they come in the person of Indiana Jones or Monty Python, fictional characters have been pursuing the Holy Grail for centuries. It is, according to tradition, the cup from which Jesus drank at the Last Supper, and that held his blood as he died on the cross; and, consequently, would be the most valuable and extraordinary artifact in the history of Christendom. Does it exist today in the vaults of some great cathedral? Was it used by its first century owners until it crumbled away? What do the scriptures tell us about who had it last, where it was, and where it might be now? Today we're going to see what's actually known about the Holy Grail, and — if we're very lucky — we may conclude where it might be. The first thing we have to do when looking into the Holy Grail is to stop talking about The Da Vinci Code. Dan Brown's 2003 thriller novel was set in a world in which some popular alternative histories of Christianity were all true, and among these was a claim that the Holy Grail referred not to a cup, but to the womb of Mary Magdalene, who bore Jesus' children. These ideas were central to the plot of the book, and controversial as they were, central to its commercial success as well. Brown has always insisted that virtually all of these alternative histories are true; however, as he is its author and very much a partner in his publisher's pursuit of profitable returns, we have little reason to suspect that Brown truly believes much of this. It's marketing for a fiction novel. As has been noted by pretty much everyone who has previously written on this subject, the bulk of The Da Vinci Code's historical background is lifted from the 1982 book The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, written by three British conspiracy theorists and dismissed by virtually all legitimate historians, and which we'll talk more about later. The bottom line is that nothing in The Da Vinci Code has any role to play in a serious examination of the historicity of the Holy Grail. As the Holy Grail's story is that it plays a key role in the final days of Jesus, we might be inclined to turn first to the Bible to learn whatever we can about it. And this is where we hit our first stumbling block, and you either already know this — or if you don't, will likely be very surprised to learn it — the Grail does not appear anywhere in the Bible at all. Nowhere. Not the slightest reference. Some people have tried to shoehorn random Biblical mentions of cups and claim those must have been it, but such efforts are all painfully weak. The fact is that whatever the Grail's origin is, it was unknown at the time the books of the Bible were written. Surely an important plot point like Jesus' blood being collected while he was on the cross would not have been omitted by the authors. The most likely explanation for why it's not in there is because that part of the story did not yet exist. So this answers one of our initial questions, which is where the Grail might have ended up at the conclusion of the Bible stories. That is "nowhere". But the Bible is not the only ancient text that omits any mention of the Holy Grail. In fact, it is not present in any ancient texts from the entire first millennium CE. This tells us that the story of the Holy Grail does not come from Christendom. In 1136, the Welsh cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth published a series of volumes in Latin titled Historia Regum Britanniae ("History of the Kings of Britain"). In it, he introduced a king known only from short snippets of various Celtic and Welsh poems, a king by the name of Arthur. Geoffrey's Arthur was an heroic character with golden armor, whose sword and lance were both named, and who was undefeatable in battle. Geoffrey introduced the characters of Merlin, Guinevere, Uther Pendragon, and Mordred. Geoffrey's Historia was so influential that it became the bed from which all later Arthurian legends germinated. Historia was notably translated into French in 1160 by Robert Wace, who added a few new elements of his own, including the Round Table and a new name for Arthur's sword: Excalibur. And it was this translation into French that yielded the richest parts of the legend we know today. French poets seized upon the story and wrote what we might describe today as "fan fiction," new stories set in the Arthurian world. And so it was in this context — a literary era in which French poets cranked out Arthurian stories like they were comic books — that one of the most influential appeared. In 1190, the poet Chrétien de Troyes conceived the heroic character of a young knight named Perceval, in his poem Le Conte du Graal ("The Story of the Grail"), which he left incomplete, as he died literally mid-sentence. Perceval's tale was the epic of a quest given to Arthur's Knights of the Round Table: to find a lost talisman, the Holy Grail, which might restore the chivalry and honor of Arthur's court. What was it? In De Troyes' work, exactly what the Grail was wasn't clear, but perhaps a bowl of precious jewels. In other authors' works that soon followed, the Grail may have been a magical stone, a platter, even a book. Exactly what it was didn't really matter; as a literary device, it was simply the object of a quest. But the reason you know about King Arthur today has less to do with 12th century French pulp fiction and more to do with the 1485 publication of Le Morte d'Arthur ("The Death of Arthur"), an English language compilation and expansion of all the stories that had come before. Nearly all of these had been in French, so this book was really the first large-scale introduction of King Arthur to English-speaking audiences. It was written by a Sir Thomas Malory, but a number of men bore that name at that time and it's not known for sure which Sir Thomas Malory was the author. This book is the source material for virtually any movie or TV show you might watch today about King Arthur. Most significantly, Le Morte d'Arthur was the first time that crucial elements were added to the Grail part of the story. Malory defined the Grail unambiguously as a golden chalice, and introduced the story elements of it having been the cup used by Jesus at the Last Supper, and also used to collect his blood as he died on the cross. Within literary studies is a field called textual criticism, which is the study of variations of a given story or manuscript over time. And within textual criticism is a specialty called stemmatics, a quantitative approach that plots variations of a story on a sort of family tree, which can be used to illustrate the descent of certain storylines, and such things as the appearance or disappearance of certain characters or other story elements within a canon. Through stemmatics, we can get a reliable sense of when certain story elements (such as a Holy Grail, for example) were first added to an existing canon (such as Arthurian legend). Together with the actual texts themselves, this is what constitutes the empirical evidence that there was no Holy Grail in the days of Jesus, indeed not until nearly 1200 years later; therefore it was never the "Cup of Christ" and never held his blood as he died on the cross, or anyone else's blood anywhere. It was a fictional plot element in Arthurian legend. It was the central talisman of Perceval's quest; no more, and no less. Over the next 800 years, awareness of the Grail story gradually intertwined with Christian beliefs, and the general public came to believe it was an actual Christian relic. By 1543, theologian John Calvin described several of the at least twenty actual vessels throughout Europe, each of which was claimed by its stewards to be the actual Holy Grail of legend. So we can forgive the casual reader of the twentieth century for defaulting to the same assumption. The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail was published in 1982 by a trio of conspiracy theorists: Michael Baigent, Richard Leigh and Henry Lincoln (later editions were republished as Holy Blood, Holy Grail). The book was a followup to three episodes of the BBC documentary series Chronicle which were written and presented by Lincoln. The authors were inspired by a well-known coincidence in the spelling of two terms in Old French, first pointed out in the 15th century: san-gréal (Holy Dish) and sang real (royal blood). It was a classic case of hyperactive pattern spotting that characterizes so many conspiratorial beliefs. This pattern-matching permeated their claims. For example, if the Grail really referred to a royal bloodline, the Grail's cup-like shape could be a metaphor for woman's womb, perhaps in the shape of the letter V. Baigent, Leigh, and Lincoln then pointed out V-like shapes everywhere they could find them, a few of which are dramatized in the book and movie The Da Vinci Code, wherein one of the characters highlights the shape of a V in the center of Da Vinci's painting The Last Supper. Was Da Vinci trying to tell us something? To draw that conclusion, we'd have to start with the assumption that any time two lines meet at an angle in a painting, the artist was conveying a hidden message containing a specific historical account of something; moreover, an important alternate history, the details of which he expected people to simply divine. Do all angles in all paintings mean this same thing? Do all angles in all artworks secretly represent different alternate histories? Or, is another explanation that the pattern-matching of these three conspiracy theorist authors was simply stuck in overdrive? This tendency is called apophenia, the abnormal perception of patterns and meaning where none exists. From the field of logical reasoning errors (discussed in detail in Skeptoid #297), apophenia is a Type I error: a false positive. Much more informally, such false perceptions are sometimes referred to as blobsquatches. The term blobsquatch comes from the world of Bigfoot hunters, some of whom are notorious for presenting an unremarkable photo of a forest scene with numerous circles and arrows drawn on it, each supposedly representing where a Bigfoot is hiding. Virtually the entire book The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail consists of apophenic blobsquatches; instances where these three authors were fooled by the many historical false positives piled onto this narrative over the centuries since the poet De Troyes first conceived of the romantic tale of young Perceval, Knight of the Round Table. And so, while it may seem a disappointing loss to find that it is an historical fact that the Holy Grail never existed, it's important to look beyond this inherently negative part of the process and focus on the positive part. It is interesting and informative to understand how the Arthurian legend was built over the centuries, and how parts of it (like the Grail) bled into the popular culture of the day and were reformed into history that people took for fact. It is equally interesting and informative to trace the process backwards and reveal how we know that the Grail never existed beyond the plot of a romantic 12th-century tale. But, perhaps coolest of all, is that today we have joined the ranks of our favorite adventurers, and pursued this greatest of all historical quarries. And arguably, our success was more complete; because while we may not have found a golden chalice, we have found something infinitely more divine: the truth behind it.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |