|

|

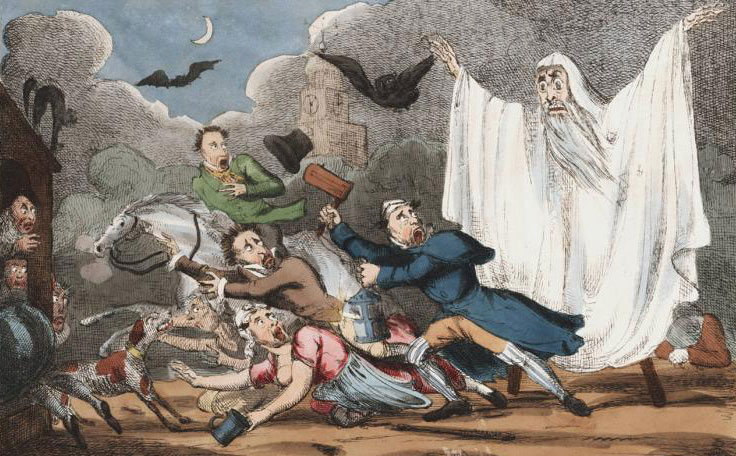

Killing the Hammersmith GhostSome possible explanations for this infamously deadly 19th century haunting near London. Skeptoid Podcast #714  by Brian Dunning This famous historical ghost case from London in 1803 is notable in that it impacted the English criminal justice system, but also in that it involved actual spectres, court testimony, one real death and possibly two more rumored deaths. Most descriptions of the case today put it all down to mistaken identity, but in point of fact, that's about the least interesting aspect of it. Today we're going to examine several possible explanations, and identify the one that best fits the facts, for this tall, white-clad phantom that might rise up and grab you as you pass the cemetery at night. The basic facts of this case, which are the ones you'll find reported most often, is that there was a ghost scare in the Hammersmith district of London. Frightened residents attributed one or more deaths to the ghost, and so a number of vigilante groups went out in pursuit of it. One night, one such vigilante encountered an all-too-human bricklayer walking home wearing his all-white work uniform. He did not respond to hails, and the vigilante shot him dead, believing him to be the ghost. Peripheral to our focus today, but still significant, is that the case ended up becoming somewhat pivotal in establishing English case law: should a person acting in good faith under a mistaken belief still be guilty of murder? The question of whether a mistaken belief can be a valid defense for murder can get quite thorny when you follow all the threads and come to questions like the apparent threat of imminent harm. The United Kingdom finally ironed this out in 2008 — 204 years after the Hammersmith Ghost. Roughly, what it comes down to today is that if the defendant perceives force is necessary to prevent harm due to some mistaken belief of his, and he's relying on that belief honestly and not unreasonably, he's entitled to the defense. But enough of that; back to our story. Addendum: For a more detailed discussion of Hammersmith's impact on English law, see this update. —BD The ghostly rumors had been floating around Hammersmith since December 1803. The area was then quite suburban with lots of farming and gardening. It was said that a man who had committed suicide by cutting his own throat had been buried in the graveyard of St. Paul's chapel of ease. A common belief at the time was that the soul of one who had committed suicide could never be at rest in consecrated ground; thus, it was excusable for many people to suspect that a ghost might be on the loose, perhaps even a belligerent one. One resident, Thomas Groom, told this frightening story:

And afterward, a popular rumor arose that a similar event took place with far more dire consequences. This creepy tale was reported in the book Old and New London (Volume 6):

Whether the culprit was actually a ghost or just a mischievous person was not finally the point though; if this being, whomever or whatever it was, was going around killing people, it needed to be stopped. So a number of vigilante parties formed, there being no organized police force in Hammersmith at the time. One such vigilante, a Mr. Girdler, had previously seen the white-shrouded ghost himself, and even pursued it. During the later court testimony, he described how he lost the ghost when it:

The reports were not all of a white-shrouded being though. During court testimony, Ann Millwood, sister of the deceased bricklayer, said the talk of the ghost she'd heard was that:

The description was mirrored by Girdler's vigilante partner John Locke:

On patrol by himself one evening, Francis Smith, 28 years old, encountered the figure of Thomas Millwood as he stepped out of his father-in-law's house just after 11pm. Millwood was dressed in plasterer's clothes, described as "Linen trowsers entirely white, washed very clean, a waistcoat of flannel, apparently new, very white, and an apron." Smith cried out:

And so he did, a single shot that broke Millwood's jaw and penetrated his spine. Writing for the Charles Fort Institute, historian Mike Dash described what happened next:

But those months were not quiet. As we see often, one highly publicized ghost sighting begets another, and another; and this time, even as Smith's trial was underway, the St. James Park Ghost grabbed the headlines. Near where Buckingham Palace now stands, two sentries of the Coldstream Guards outside the Wellington Barracks — in separate incidents — both reported a horrific sight. One signed the following statement:

Both men were so affected they had to be hospitalized, and publicly declared their belief that it was a ghost. The papers reported that others had seen it too. The Times published a debunking very soon after. Their investigation asserted that a pair of students from nearby Westminster School set up phantasmagoria equipment in an empty house across the street and hoaxed the poor guards. Phantasmagorias were still reasonably new at the time; the classic application used what was called a magic lantern. This was a camera obscura in the form of a box with a projection lens on one side, or even just a pinhole. Inside the box, an image or even a small model of an object was placed, made as bright as possible with a lantern. An image would be projected onto an opposite wall. In the most elaborate phantasmagoric performances, such as those performed on the stage, a light see-through fabric could be hung to make the spectre almost appear to be standing beside the performer. Today this seems like a very poor explanation. With nothing more than a lantern — this was well before the invention of the electric light — it would be extraordinarily difficult to get such a projection bright enough to be visible over anything more than a very short distance. At any distance the image would have been hopelessly big and diffuse. Decent focus would have been nearly impossible to achieve, and without an obvious fabric screen in front of the soldier the image would have only been visible on the flat side of a building; but this was said to have been across the street, facing toward the soldiers, the geometry making this explanation implausible. Phantasmagoria shows had been playing in London since 1801, so they were still new and novel, and some percentage of Hammersmith locals might have seen one. Those who had probably told amazingly exaggerated accounts to their friends — 50% of whom were illiterate in London at that time — and it's no surprise that people may have had an inflated idea of what a magic lantern may have been able to accomplish. In Skeptoid #550, we told the tale of the Mad Gasser of Mattoon, a case of mass hysteria driven by irresponsible news reporting. Mass hysteria doesn't mean people are running around hysterically in the streets. It's much more subtle. People tend to make interpretations based on expectations; and when the newspapers, or other popularly shared information, set specific expectations — in this case, a ghost — it's common and normal for us to err on the side of that expectation when we see anything unusual. It can even be something that we may not even notice in the absence of those expectations. If we can believe the sworn court testimony, there were people in town who had been attacked, and who had seen someone wearing a white sheet. With that kind of information out in the wild among a public for whom belief in ghosts was the norm, the extraordinary outcome would have been one in which there was no Hammersmith ghost, and no headless woman in St. James Park. No phantasmagorias or accursed suicide victims needed. Addendum: It turns out that an actual person dressed up in a sheet has been identified as the one who probably started the Hammersmith ghost episode, and was even arrested for it. See this followup episode for the details. —BD A footnote that may be of interest to some: Most sources say that Smith killed Millwood with a shotgun. There is no contemporary source for this; the only gun described in the court testimony was Girdler's pistol. A medical examiner named Flower stated that there was a single gunshot wound of small shot, "about the size of No. 4." If it was indeed a shotgun pellet, it could have been either 3mm birdshot by the English system (unlikely to have broken a man's jaw) or 6.1mm buckshot, equivalent to about a .24 caliber pistol round, within the scope of error of Flower's estimate. Which one the excitable Mr. Smith actually carried is lost to history. —BD

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |