|

|

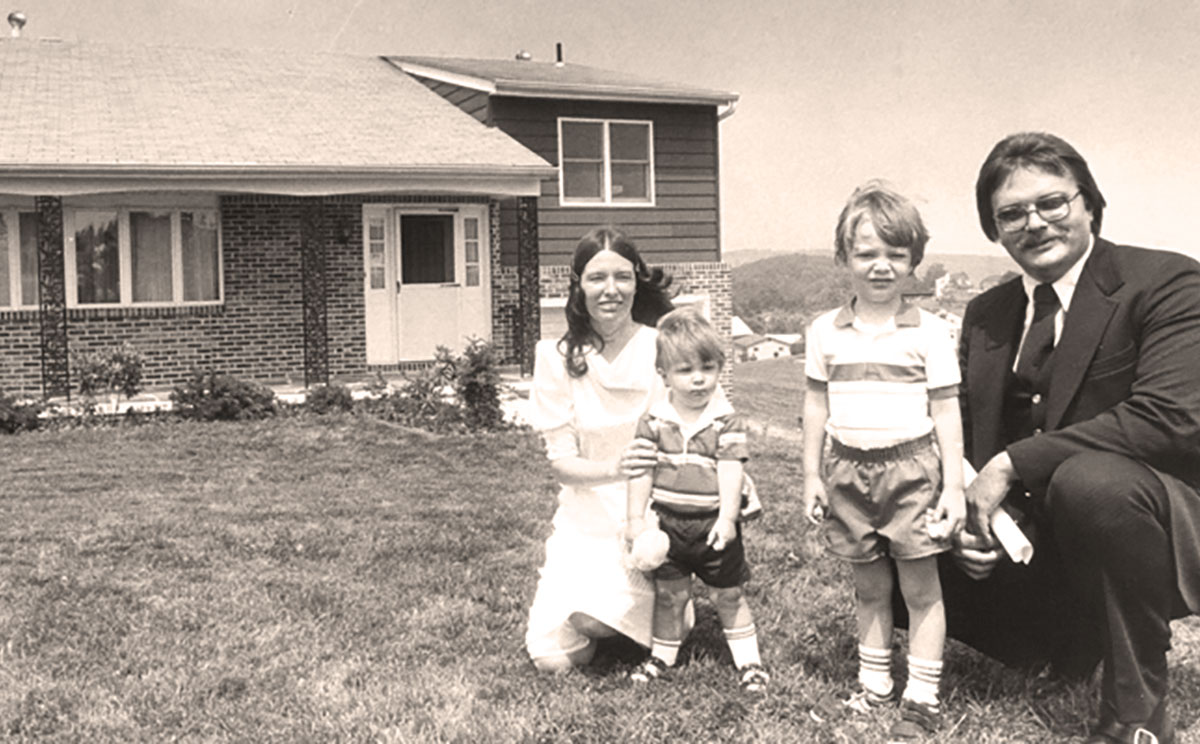

Radon in Your BasementIs this gas a risk you should worry about, or is it just another homeowner scam? Skeptoid Podcast #698  by Brian Dunning We've all seen the advertisements — you need to have your basement checked for radon gas, as it seems to represent some nebulous health threat, and it might be in your house right now. Should we pick up the phone and call the toll-free number? Or, instead, should we skeptically evaluate the advertisement and the warning? The average person on the street can be easily forgiven for not knowing which is the best way to proceed. For this threat of radon gas sounds both complicated and immediate, and it sounds like ignoring it completely might be risky. Today we're going to look at the real threat of radon gas in your home, and see what — if anything — you should probably do about it. Radon is one of the noble gases, just like helium and argon, on that far-right column of the periodic table. At atomic number 86, it is the heaviest of the naturally-occurring noble gases, just about 8 times heavier than air — so if you were to open a flask of it, the invisible substance would fall straight to the floor, or flow downstairs into your basement if you have one. It's also radioactive. It's the most unstable of the noble gases; its most stable isotope, 222Rn, undergoes alpha decay, spitting out a helium nucleus and decaying into polonium, which then decays into other things and so on and so on. Radon does this pretty rapidly, having a half-life of only 3.8 days. With such a short half-life, not a lot of radon exists at any given time, so it's actually very rare. However, as quickly as it goes away, more is being created all the time. Uranium and thorium, among the most abundant of the heavy elements in the Earth's crust, are what decay into radon. And so, seeping up through the ground — worldwide — is a constant, always-on supply of brand-new radon gas. Obviously it doesn't take a genius to realize that a constant source of radioactive gas blowing on all of us all the time might well represent a problem. But then we also have to stop and consider that we spend our entire lives bathed in all kinds of radiation: electromagnetic and energetic particles from the sun, cosmic rays, and all the radioactive elements on Earth permeate every bite of food we take. And that's to say nothing of the manmade sources, most obviously that from coal-fired power plants, plus medical and airport X-rays and everything else. Generally, we can live our lives exposed to this natural background level of radiation and not suffer any health consequences from it. So while radiation from radon fits the pattern of natural background radiation, the idea of its tendency to concentrate inside our homes gives us cause to make a truly skeptical examination of how big a threat that actually is. Alpha emitters like radon are generally not terribly dangerous when they're outside your body. Alpha particles — consisting of two protons and two neutrons — are heavy and use up their energy very quickly. They generally only travel a very short distance from the atom they came from, perhaps a few centimeters. They're also easily stopped and are unable to penetrate either your clothing or your skin. Where you get into trouble is if you inhale or ingest an alpha emitter. When you breathe in radon, you're taking it directly into your lungs where its fast-acting decay fires these short-range alpha particles directly into your lung tissue with no protective barrier at all, sometimes causing severe damage to cells and DNA. The more often this happens to you, the greater your chances become for one of these damaged cells to turn cancerous and develop into a lethal case of lung cancer. This is not the first Skeptoid episode to evaluate the true risks of widely-publicized natural processes that invade our homes. Episode #494 was about black mold, claimed on the Internet and in advertisements to be a tremendous health risk for everyone. It turned out the truth was so much milder that for most people, remediation is not recommended at all, as mold poses little or no danger for almost everyone. The bottom line on black mold is that expensive services to tear apart and rebuild your kitchen by guys in space suits and respirators is usually just a way to sell people unnecessary services. As much as anything else, that skeptical review of black mold is what motivated this episode on radon gas, as well as other popularly trumpeted, non-specific, quasi-scientific notions like "sick building syndrome" and "multiple chemical sensitivity". Is radon an exaggerated bogeyman designed to separate naive homeowners from their money, or is it something we should realistically be concerned about? Nobody had thought much about this until 1984 when Stanley Watras, an engineer at the still-under-construction Limerick nuclear power plant in Pennsylvania, set off alarms on the newly-installed radiation detectors at the plant's entrance. Nobody could figure out why, as the plant hadn't been fueled yet. Investigating, engineers from the plant found that his clothes were contaminated from radiation he appeared to picked up at home; and when they tested at his house, they found levels 20 times higher than in a uranium mine! The Watras home was built right on top of a natural fountain of radon gas. From then on, regulators started thinking about the health effects of radon accumulating inside homes. It turns out that radon represents a real risk for everyone. In the United States, there are about 21,000 deaths annually from lung cancer caused by radon inhalation. To put that in perspective, it's slightly higher than the number of deaths caused by drunk driving, which is about 17,000. So if you consider how much time you spend worrying about drunk driving, you should be just a little more concerned about radon in your house. Calculating your real risk is a bit more complicated. Your risk depends on other things as well: two most significantly. The first is where you live, because natural levels of radon vary a lot; and the second is whether you smoke. Of that 21,000 annual deaths from radon, only 2,000 of them are among people who have never smoked. Smoking is just not good for you, and among its hazards is making your lungs far more vulnerable to the kind of damage done by alpha radiation, though the exact mechanism for this isn't yet clear. Geology is what determines how much radon is seeping up out of the ground where you live, so a wise first step is to search the web for radon map and see what your area looks like. A number of websites provide interactive maps that show you average levels in your town. In the United States, many of the northern states range pretty high, while much of the south and the west coast tend to run lower. But everywhere is affected by local variations — remember Stanley Watras's house — so don't take any generalizations as authoritative. This is a great time to take a moment to talk about radon levels; how we measure them, and what levels are considered too high. Radon radiation levels are measured in picocuries per liter (pCi/L). At 1 pCi/L, there average just over 2 nuclear disintegrations per minute in a liter of air, resulting in 2 alpha particles being emitted. As radon is naturally occurring, even the fresh outdoor air has a reading, averaging about 0.4 pCi/L, and ranging as high as about 0.75pCi/L. So there's really no such thing as 0 pCi/L of radon — it simply isn't possible here on Earth to be completely free of the risk of lung cancer from radon. The trick for regulators has been establishing a target level that we stay below for an indoor dwelling, and this has been done through (among other things) cost/benefit analyses. In 1986, economists with the Environmental Protection Agency undertook to figure this out. They determined that in 95% of the cases, it was possible to reduce radon levels to below 4 pCi/L; and that in 70% of the cases, it was possible to achieve 2 pCi/L. Getting much below that turned out to be either not possible or prohibitively expensive. At the same time, they calculated how many lives would be saved at which levels and at what costs, and what emerged was a point of diminishing returns. At 4 pCi/L, it cost $700,000 to save a life; at 3 pCi/L, that cost went up to $1.7 million; and at 2 pCi/L, it would cost $2.4 million to prevent one death from lung cancer. Furthermore, at 2 pCi/L and below, concentration is low enough that the measurements became unreliable, with false positives and false negatives giving invalid data. So the action level was ultimately established at 4 pCi/L. What this means is that if your home has a reading higher than 4, it is recommended that you take remediation action. But if your level is 4 or less, then it's not worth doing anything. So how should you proceed if it turns out yours is one of the houses which calls for mitigation? There are a number of ways this is done, and every house is different. In the United States, the best first step to take is to locate your state's radon office — every state has one — and check their list of certified or licensed radon contractors. Once they check out your house, there are a variety of different things they might do. Usually the best measure is prevention — find how the radon is getting in and stop it, and this is what the EPA recommends. Sometimes the best mitigation is ventilating the radon to the outside; sometimes it's a combination of both. A certified or licensed radon contractor will figure out the best solution for your particular house structure and the geology upon which it sits. So let's wrap this up with an official Skeptoid recommendation. Natural radon outdoors is indeed a part of the normal background radiation levels that aren't likely to hurt us, but its tendency to concentrate inside our homes sets it apart from all those other sources. Your risk from radon is low but real, and it's very easy and inexpensive to do a test. You don't need to buy a fancy electronic gadget or hire an expensive person. But you do have to test; you can't just sniff for it: remember radon is a noble gas, meaning it has almost no chemical reactivity, thus you won't be able to smell it or taste it. Luckily, at any hardware store or online retailer, you can buy a kit for around $20. You lay the detection strip on the floor for a few days, then you mail it in and get the results by return mail. This is well worth doing for everyone. 1 in 15 homes in the United States comes back at 4 pCi/L or higher. Those are pretty short odds, and $20 is a bargain just to make sure you're not among the unlucky ones. If you've ever smoked your risks are considerably higher, so you should really do it. Either way, it could well turn out to be one of the easiest preventive measures you ever take to protect your family's long-term health. Correction: An earlier version of this said thorium and uranium are among the most abundant elements in the Earth's crust, accidentally omitting the important qualifier heavy elements. —BD

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |