|

|

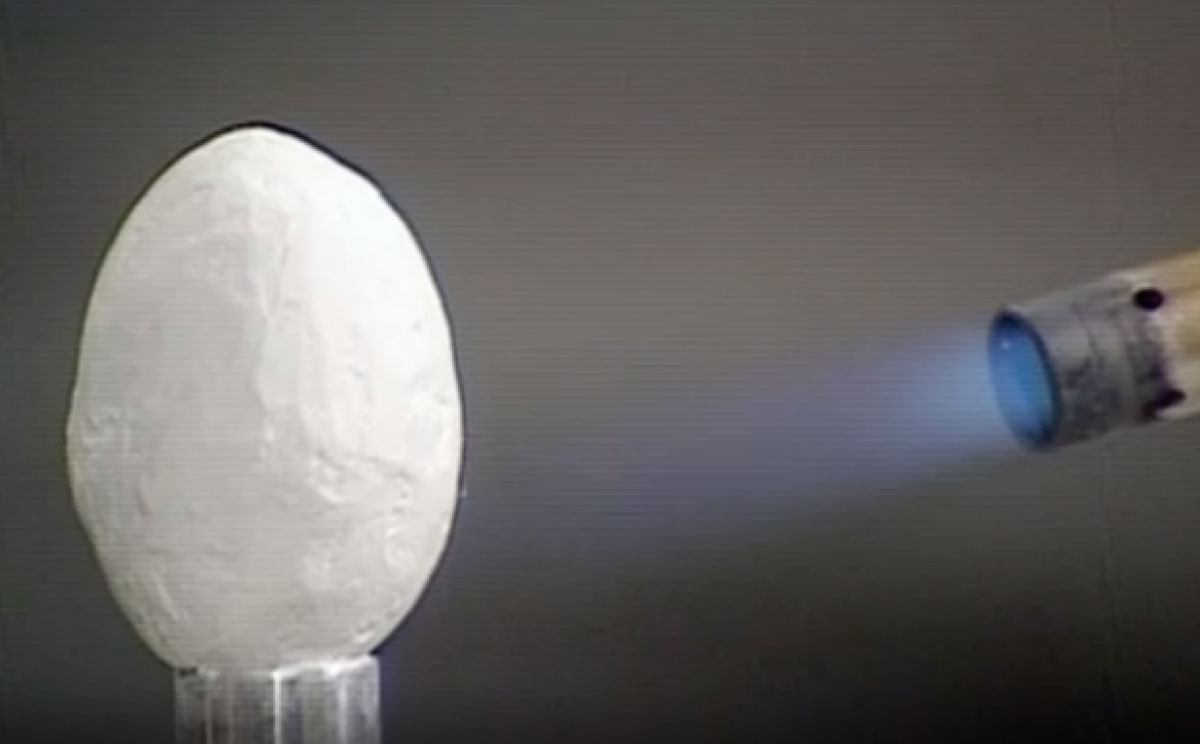

Starlite, the Magical Mystery MaterialSkeptoid Podcast #684  by Brian Dunning It was said to resist nuclear explosions, the most powerful laser beams, and any amount of heat. It was cheap and easy to make, with countless applications throughout both safety and industry, and could have earned billions for its inventor. Yet, this incredible material called Starlite is nowhere to be found today, and Internet pundits charge that it was suppressed or stolen by the biggest corporations. What is the true history of Starlite, and why is its humble inventor not renowned as one of our greatest? Maurice Ward was a hairdresser in North Yorkshire, England. Although he had no training or education in chemistry or material science, he used to like to experiment with new formulations for hair coloring, which he did quite successfully by all accounts. He was also intensely interested in fire protection, and mixed up various compounds until he came upon one that seemed to meet all his goals. Named Starlite by Ward's granddaughter, the compound was a white powder to which PVA glue is added to create a desired consistency. PVA is polyvinyl acetate glue, a common and relatively safe glue similar to familiar Elmer's or wood glue. Ward had a few fits and starts showing it off to people he knew, always with the same demonstration. He took a raw egg, plastered it over with Starlite and pointed a blowtorch at it for several minutes. Then he'd ask someone to pick it up — who found it perfectly cool to the touch — and crack it open, showing that the egg was still raw. It hadn't been cooked at all, being perfectly protected by that thin coating of Starlite. Finally Ward's big break came. In 1990, the BBC television show Tomorrow's World did a segment on Starlite, performing the exact same egg trick and promising that the material would revolutionize everything from the military to commercial and space travel. Sir Ronald Mason, a retired former Chief Scientific Advisor to the Ministry of Defence, saw the show and decided to join Ward in the Starlite project. Through his connections, Mason was able to arrange some tests by the UK's Defence Research Agency. These included hitting it with high-powered lasers at the Atomic Weapons Establishment in Foulness and at the Royal Signals and Radar Establishment in Malvern; plus a trip under NATO auspices to the White Sands Missile Range in the United States where it was subjected to extreme heat simulating that from a nuclear explosion. Ward and Mason reported that Starlite withstood all of these. Glowing reports in hand, they set out to commercialize it as the newest miracle product. A barrage of press releases in 1993 resulted in articles in respected publications such as Business Week and Jane's International Defence Review which trumpeted these positive results. They soon found another champion, a man named Rosendo "Rudy" Naranjo, an engineering manager at NASA. In 1997, Naranjo directed their major subcontractor, Boeing, to perform a series of tests on Starlite to see if it might be useful to NASA. These tests, the results of which are detailed in a 33-page report, were conducted in December 1997 at two Boeing facilities and considered three potential applications, using about 15 various formulations of Starlite. The first test was resistance to lasers, and it was found that most Starlite variants performed as well as other existing materials:

The second was as a fire and thermal barrier, and again, most Starlite formulations performed as well as existing materials:

The third application was as a flameproof liner for airliner cargo bays, and here it stumbled a bit. Only some formulations worked, and then only when applied much more thickly than conventional materials:

Nevertheless, following the Boeing tests, there appeared a four-page memo on NASA stationery — purportedly written by Naranjo — that gives Starlite the highest praise imaginable. This memo is widely available online, and is waved by Starlite's advocates at every turn. However, the NASA memo is where Starlite's story ended. Ward never managed to sell Starlite to Boeing or NASA or anyone else. He never gave away the formula, and when he died in 2011 it's said the secret died with him. Today that secret is with StarliteTechnologies.org, a guy who says Ward shared the formula with him before he died, and he now wants Ward's daughters to "realize the dream of Starlite." His website is a collage of Bible verses, random music videos from YouTube, a completely empty crowdfunding campaign, and ranting conspiracy theories:

Another company, Thermashield, also makes similar claims about having obtained the formula from Ward's family. Their website's a bit cleaner. In fact, throughout YouTube and the rest of the Internet you can find similar conspiratorial claims. Ward is often afforded a sort of mystical superhero status like that given to Nikola Tesla by alternative science believers. The StarliteTechnologies.org guy calls Ward's failed attempts to sell Starlite "the biggest David vs. Goliath story of all time." I'll let you in on where my head was when I began to research the Starlite story. After reading everything, I found Ward's to be a familiar story: A lone amateur inventor, working in isolation with no collaboration from relevant experts, claims an incredible discovery beyond the abilities of all the world's top scientists; but some conspiracy of powerful corporations suppresses it and prevents him from realizing any profit. Most specifically, I was thinking of the old hemp conspiracy theory. The claim here — promoted mainly by marijuana enthusiasts — was that industrial hemp was a superior raw material from which to manufacture virtually any kind of product, so all the big chemical companies conspired to have it banned. The truth, however — as discussed in Skeptoid #401 — is that the tiny amount of industrial hemp grown is due not to any conspiracy but simply to the fact that isn't all that useful of a product; there are better alternatives for every potential application. This guided my expectation of where I thought the Starlite story might lead. If every big chemical company in the world turned down Ward's invention, I expected to find out early on that Starlite simply wasn't very exceptional. That is, of course, exactly what came out in the Boeing report. A few formulations occasionally performed better than conventional materials; most, at best, matched their performance; and others failed. It's noteworthy that in the version of the Boeing report available online at StarliteTechnologies.org, only 23 of its 33 numbered pages are included. What's missing, and why? There are other reasons we shouldn't be surprised that Boeing did not recommend Starlite to NASA for anything, besides its failure to outperform existing materials. Ward was apparently perversely paranoid about Starlite. He never discussed its ingredients; he refused to patent it due to the requirement to list its ingredients; he refused to leave samples with Boeing which would have allowed the required more comprehensive testing. He also insisted on maintaining at least 51% ownership and refused to consider licensing, and is frequently on record saying Starlite was worth multiple billions of dollars. If he was demanding billions of dollars while refusing to let anyone know what it was, it's little surprise his sales went nowhere. Moreover, the basic ingredients were never hard for knowledgeable people to divine. Besides the PVA glue, lots of guys on YouTube have replicated the egg demonstration with ingredients as simple as cornstarch and baking soda, or even just powdered sugar. Mick West, on his website Metabunk, showed video of a number of such tests he did himself, and concluded:

In 2018, Ward's daughters brought a sample to materials scientist Mark Miodownik at University College London for a BBC video. He put their Starlite to the torch and explained how such materials work:

Such paints are called intumescent paint, and they've been around and been used for fire protection for a long time; the first one was patented in 1948. Maurice Ward may have developed a fine one, but by no means was it revolutionary. However, we do have cause for concern that Ward's Starlite may have been even less than that. Recall the NASA memo — the four pages on NASA stationery, addressed to nobody, signed by nobody, but giving the most grandiloquent sales pitch in history — stating that Starlite has "the potential to revolutionize contemporary warfare, modern industry, commercial transportation, even the space program." It turns out the memo is fake. We know this because actual NASA memos do spell "National Aeronautics and Space Administration" correctly on their letterhead (this one's missing an "s"); and they use the actual NASA logo (called the "meatball insignia"), not a slightly-off mocked-up version with a font that's not even close. The actual meatball insignia is so widely available online that it's hard to grasp how someone could have faked this so badly; but the main point is it's fake. This letter did not come from NASA, and whoever created it tried to deceive us into thinking that it did. This gives us cause for grave skepticism about all the other documents used to support the Starlite story, including the Boeing report. Excluding documents that come from the various Starlite websites, I found only a single reference to anyone from Boeing mentioning it. It was a 2002 interview with Allen Atkins, then a vice president at Boeing Phantom Works, published in the Tennessee Tech quarterly Visions — and even it does not mention Starlite by name. Discussing a variety of fireproofing technologies Boeing had looked at, Atkins said:

No lasers, no simulated nuclear blasts, no cargo bay liner tests: just the party trick with the egg. I'm sad that the Starlite story ended in such disappointment. I don't doubt that Ward created a capable intumescent coating, and I don't doubt that at least some of the tests described actually did take place; maybe all of them did. However, after so many red flags, I have grave concerns about the reported results of all of the tests, as it seems all such reports trace back to the Starlite people themselves. There's every reason to believe Ward was absolutely sincere in his desire to protect people from fire, and every reason to believe he had a natural gift for chemistry and materials science. But as for the Starlite product itself, it probably deserves no special mention in the history of fire protection, so much as it does in the annals of urban legendry.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |