|

|

Cueva de los Tayos and the Lost Metal Library, Part 2A closer look at how bad the evidence is that a cave exists filled with golden alien wonders. Skeptoid Podcast #638  by Brian Dunning Last week in Part 1, we discussed the history of the explorers and authors who believe that an ancient advanced civilization, possibly alien, constructed an elaborate high-tech library of metal plates and laser beams inside a cave in Ecuador filled with golden wonders. They've never found it, but the input from authors like Erich von Däniken (Chariots of the Gods) and golden artifacts said to have come from the cave keep interest alive, and keep the television networks producing documentaries promoting the library as actually existing. Today we're going to go through all that evidence, and see whether even a modest amount of genuine research could have spared some of these hopefuls immense amounts of time and money. To recap: early evidence from Cueva de los Tayos started with an oral history from Ecuadorian army officer Petronio Jaramillo, who said he swam into the treasure room when he was a boy, and thus knew its location. A local priest, Father Carlo Crespi, kept a collection of astonishing golden relics from the cave, which he obtained by trading with the indigenous Shuar tribe. These inspired the Hungarian-Argentine amateur explorer Juan Móricz, who conducted expeditions to the cave throughout the 1960s. Móricz's doings reached Erich von Däniken, who wrote of an expedition he took into the cave with Móricz, which formed the centerpiece of his 1972 book Gold of the Gods. These seminal characters laid the groundwork for everything that followed as the cave became a fixture in the "ancient aliens" mythology. In their footsteps, two generations of Irish amateurs, Stan Hall and his daughter Eileen Hall, have conducted large, highly public expeditions to the cave — Stan in the 1970s with astronaut Neil Armstrong, and Eileen in the 2010s with various cable television networks. And, of course, references to the golden marvels and the metal library's galactic wisdom permeate the alternative history literature. Our story finds its fulcrum with von Däniken's book. What we see so often with pseudoscientific claims today is that they make a great public splash, and the science-based debunkings that follow swiftly are ignored by a credulous public hungry for sensationalism. This is precisely what happened with von Däniken. Scarcely had his book come out promoting the wonders in the cave when the German magazine Der Spiegel consulted with an actual scientist in Ecuador, and learned a number of facts:

Then in 1973 Der Spiegel interviewed Móricz to ask about the time he took von Däniken into the cave. Móricz told them:

Von Däniken is quite the colorful character. While he was writing Chariots of the Gods, he wasn't exploring Mesoamerica and studying archaeology; he was mostly busy bouncing between courtrooms in Switzerland and Austria where he had various convictions for theft, fraud, and embezzlement, served at least two different terms in prison, was described by one examining psychiatrist as having a "tendency to lie", and by another as "a liar and a criminal psychopath". Of course this says nothing about the accuracy of his ancient alien claims, but it does tell us something of how he spent his research time, compared to archaeologists who spent those same years actually in South America. Faced with these new charges from Der Spiegel and Móricz that his claims about the cave were factually untrue and that he'd lied about going there (no great surprise), von Däniken was challenged by Playboy magazine in a famous 1974 interview. His explanation for the discrepancy was:

Considering that he has never produced any photographs or evidence that he was ever there, and considering that there are only denials that he ever visited and no corroborations, we can conclude that von Däniken added nothing of value to the story. So we turn to the next person in line: Móricz. Der Spiegel pressured Móricz on why he'd never brought back any evidence at all from the caves, not even a photograph of the alleged metal library — his reason for the lack of photographs was that a flash might have damaged them. Then why not bring back just one of the thousands of plates?

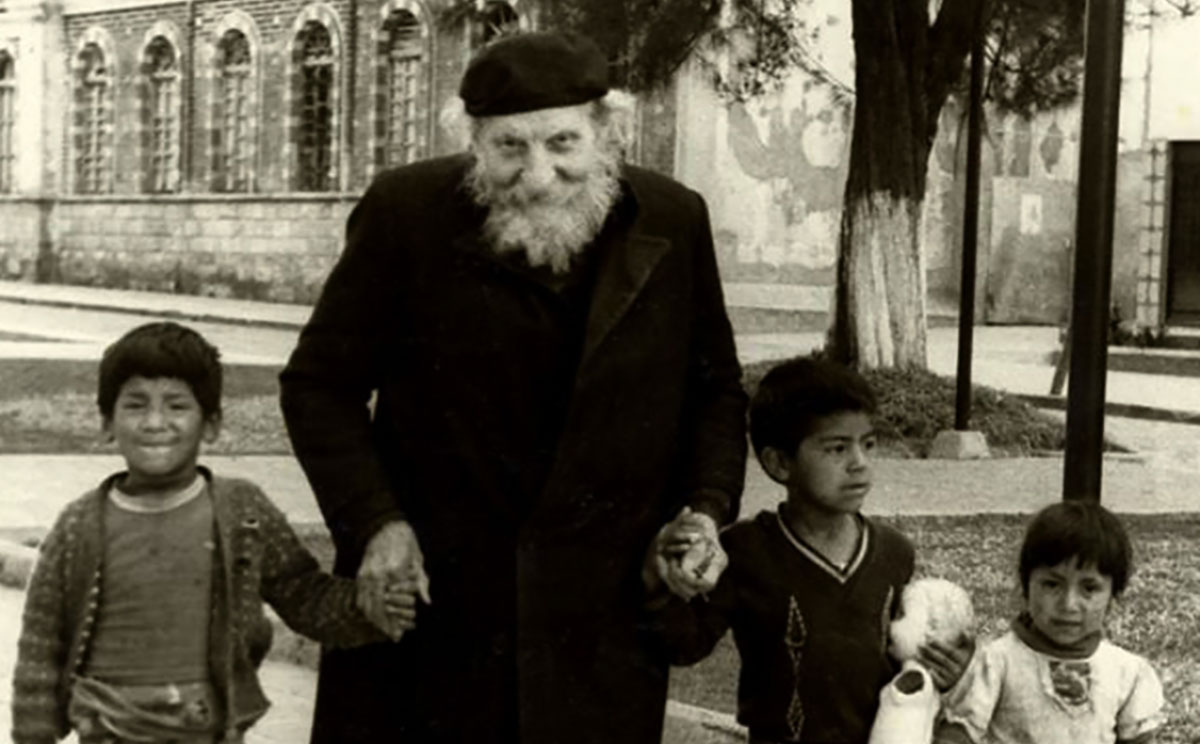

So we can fairly ask Móricz to go sit with von Däniken in the corner of people who just made stuff up as they went, no matter how outlandish; and given that their claims were so clearly at odds with true Ecuadorian history, it seems clear that little credibility is warranted. Which leads us to the physical evidence: that impressive collection of artifacts held by Father Crespi. Carlo Crespi was a universal figure in this tale; everyone visited him and studied his artifacts. Even the legendary magician and debunker James Randi spent time with him in the mid-1960s, before von Däniken's books, after hearing local tales of treasure caves. As did other authors who visited, Randi found Crespi to have abysmal personal hygiene — he was likely mentally ill — and that:

Crespi eagerly conducted Randi through the three rooms of his museum at the church, and Randi described the contents of the "third room" said to be where Crespi kept the most valuable treasures:

As Randi's description is identical to that given by other authors, we can scratch Crespi's artifacts off our list as well. Our story finally comes to its final thread — much like the headwaters at the very source of the Río Coangos — with Petronio Jaramillo, whose story of seeing the gold with his own eyes as a young man inspired all of this. His story was told by Eileen Hall, as she heard it from her father Stan Hall, as it was told to him by Petronio himself many years before. She related it in a 2010 interview. When Petronio was a boy, his uncle Humberto Jaramillo was on his deathbed, and told young Petronio exactly where the cave was, exactly how to enter it, and about the vast riches inside. Petronio told how he then, at the age of seventeen, made his one and only trip inside the cave, accompanied by his native friend Mashutaka. The year was 1946. He had to swim underwater to access the treasure, which prevented him from bringing a camera. Inside, he found the stupendous alien treasures, just as von Däniken described them a quarter of a century later. Journalist Pino Turolla spent many years in Ecuador trying to piece together the bits of the legend of Cueva de los Tayos, and had been after Jaramillo's story for a long time. In 1968, years before Stan Hall met Jaramillo, Turolla met with him at his home in Quito. Jaramillo was then a retired Major in the Ecuadorian army. In a recorded conversation transcribed in Turolla's 1980 book Beyond the Andes, Jaramillo told how he had befriended Mashutaka when they were boys, but that it wasn't until 1956 when he chanced upon Mashutaka again while on a jungle army patrol. It was then that Mashutaka told him about the cave and the two of them went and saw it. It was a completely different story than what Jaramillo had always told Stan Hall — and irreconcilable in all its major details. Turolla spent a long time trying to track down Mashutaka to get his version of the story, and in 1970 he finally caught up with him. Turolla wrote:

I recently got in touch with an explorer in Ecuador named Stan Grist, who also wanted to get to the bottom of Jaramillo's story. Jaramillo himself being dead, Grist was able to track down his ex-wife in 2006. Grist wrote:

In the interview, Sra. Jaramillo said the novel had been inspired by his early days when he'd known Mashutaka as a boy. She said:

And the real kicker is that all of this information had been available to honest researchers before von Däniken wrote Gold of the Gods, before Stan Hall mounted his massive 1976 expedition, and long before today's TV networks began pouring money into programs about sensationalized "ancient aliens" expeditions to nowhere. It's a case of researchers seeing only what they want to see; avoiding information they suspect won't support their preferred belief, and seeking out only whatever confirms it: seeing ancient aliens in von Däniken's fraudulent fiction, and seeing golden wonders in Father Crespi's copper toilet tank floats. Whenever you hear a story like this one, with decades of proponents insisting upon alternative history, you can be assured that if you open your mind to what non-proponents have learned, you will find your skepticism amply rewarded. And perhaps that's where the real treasure lies in wait.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |