|

|

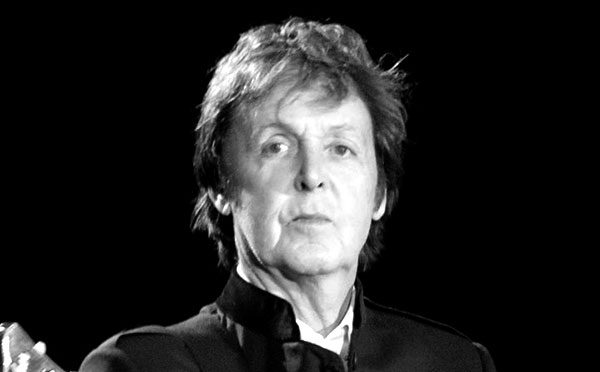

Paul Is DeadThe origins and history of the urban legend that Paul McCartney died and was replaced. Skeptoid Podcast #594  by Brian Dunning Today we're going to stroll across the famous crosswalk outside Abbey Road Studios in London and have a look at an infamous rumor that we've all heard: that Beatle Paul McCartney died mysteriously in the 1960s and was replaced by a lookalike, who now lives and performs as Paul McCartney. Apparently, the Beatles left us many clues to prove that it's true, both in their music and on their albums. We're going to have a look at some of those clues, and also the genesis of the story, and maybe answer a question: Does the way a story came about impact how likely it is to be true? As with a number of other urban legends, the story of Paul McCartney having been killed and replaced with a lookalike had an inauspicious beginning: a phone call into a radio program. It was a student from Eastern Michigan University named Tom Zarski who called into a Detroit radio station on a slow Sunday afternoon on October 12, 1969. The DJ who took the call was Russ Gibb. Little did he know, but that day was to be one of the biggest of his career. So much so, that 45 years later, in 2014, Gibb did an interview with BBC Scotland to talk about how it happened:

When you read about the claim that Paul is dead, it turns out there is a surprisingly specific story for what happened. It was in the wee hours of Wednesday, November 9, 1966. The Beatles were working late at Abbey Road Studios in London and got into some argument. Paul got really mad and stormed out. He took off in his car at 5:00 in the morning. While driving, he was distracted by a pretty meter maid identified as Rita, and missed a red light as a result. He crashed and was killed. Stunned by this turn of events, the surviving Beatles elected not to say anything about it, but instead held a Paul McCartney lookalike contest. It was won by William Campbell, an orphan from Scotland. He was given minor plastic surgery, but since it still wasn't quite right, the Beatles changed their look and all grew facial hair to disguise the remaining differences. From that moment on, William Campbell ceased to exist, and Paul McCartney lived on. One might be inclined to be skeptical of this story. Some guy happening to look a bit like Paul McCartney is one thing, but that he also happened to sing and perform exactly like him, and was his equal as one of the rare musical geniuses of our age, and Paul's family and friends all being fine with this switch as well, and there being no police or medical or news records of the violent death of one of the world's most famous people on a public street -- there are an endless number of red flags suggesting the story might not be true as reported. That's to say nothing of the fact that this story is almost purely an American phenomenon, and was virtually unknown in England where it supposedly happened, and where the Beatles lived and worked. So where did all these specific details come from, if there are no records of the crash? Well, on the Sunday of the Russ Gibb broadcast, another student was also listening. He was Fred LaBour, a journalism student at the University of Michigan (and today, he's the bass player for the successful western swing band Riders in the Sky). Two days after Gibb's radio show, LaBour published a full-page article in the Michigan Daily. It began:

All of the details of Pauls' death come from LaBour's article, and it's also the earliest place most of the popularly-known clues are mentioned. So let's have a look at these clues the Beatles are said to have left us. Many of them are details in the album covers, like Paul being barefoot and out of step with the others in the famous crosswalk photo on the cover of Abbey Road. But since this is an audio show, let's focus on the clues found in the actual music. Most come from three of the Beatles albums that came out after the alleged crash in 1966 and before Gibb's radio show in 1969. They are Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, Magical Mystery Tour, and the White Album. First let's revisit the one that so impressed Russ Gibb. It comes when we play the song "Revolution 9" backward. It seems to say "Turn me on, dead man, turn me on": But let's look at the specifics. At five in the morning on a Wednesday, Paul was driving home. Here's from the song "She's Leaving Home": And from "Good Morning, Good Morning": And then, he saw her: And again from "Good Morning, Good Morning": The distraction caused him to miss the light and crash, as described in the song "A Day in the Life": At the end of "Strawberry Fields Forever" it sounds like "I buried Paul": Then when we play "Im So Tired" backward, it sounds like "Paul is dead now, miss him, miss him, miss him": They also left a hint about William Campbell, the lookalike, assuming Paul's role. In the song "Hello, Goodbye", Campbell, singing as Paul, offered this nod to his predecessor: And reversing part of "I Am the Walrus" we get "Paul is dead, ha ha": The walrus turns out to play a slightly larger role: But according to the record jacket, the song's complete title is "I Am the Walrus, No You're Not! Said Little Nicola". So then, who was the walrus? For this, we turn to the song "Glass Onion": Why all this with the walrus? According to Fred LaBour, the word walrus is Greek for corpse, thus it's clear that the Beatles were trying to reveal the truth about Paul's death. Except for one thing: walrus is not Greek for corpse; or Greek for anything, for that matter. LaBour made the whole thing up, and has said so outright on many occasions. His entire article in the Michigan Daily, except for what he gleaned from Russ Gibb's radio show, came from his own imagination, and a stack of Beatles albums that he looked through for ideas. Nevertheless, his article went viral. It was even mentioned in both of the two most popular magazines of the day, Time and Life. LaBour said:

It grew and grew. He was even asked to appear as a witness on a TV special conducting a mock trial with celebrity attorney F. Lee Bailey. LaBour was going to have to lie on national television!

Even today, decades upon decades later, hoaxers are still coming up with pretend evidence: there's a fake deathbed confession from George Harrison, there's a book available making far-out biometric comparisons of Paul's face before and after the alleged crash, there's even a fake documentary movie called Paul McCartney Really Is Dead that implicates Britain's MI5 as being behind the switcheroo. In short, it goes on, and on, and on. Come up with a wacky death hoax about a famous person, and the Internet pretty much guarantees that your story will not only survive but grow, as all of today's "new evidence" demonstrates. Update: The February 1967 edition of The Beatles Book (number 43) includes a dismissal of a rumor that Paul died on the M1 on January 7th. See the Listener Feedback episode #599 for more info. —BD

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |