|

|

No, You Shouldn't Question EverythingSkeptoid Podcast #530  by Brian Dunning Yes, it's an obvious clickbait headline. It's the kind of statement that, taken by itself without explanation or context, is sure to raise the ire of nearly anyone who considers themselves to be of a skeptical or scientific bent. Clearly, nothing should be above being questioned; but there are also a lot of ideas that just aren't worth questioning. Today I'm going to present my case for why you shouldn't question everything. Speaking from a strictly philosophical perspective, of course you should question everything. This is a fundamental of reasoning schools from luminaries such as Socrates and Descartes. Questioning everything is a moral imperative — stemming from the recognition that nothing is above being questioned — but moreover, it's the way we learn and grow. Consider these basic reasons to question everything:

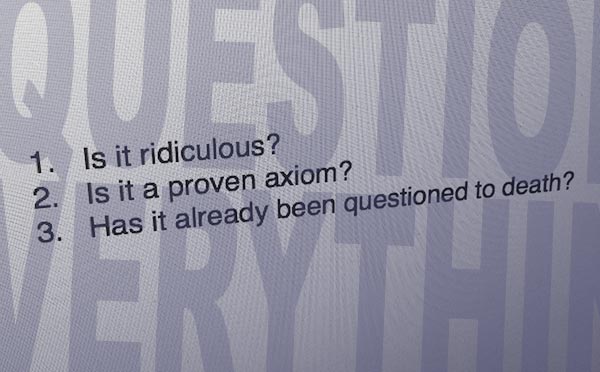

And all of this is to say nothing of scientific inquiry into the unknown — not mere testing of existing knowledge, but the development of new knowledge. Finding the right questions to ask, asking them, and seeking answers is the central process. But investigating these things we don't yet understand is a given; it's the first step in learning about anything. It's when we come to the things we think we do understand where the importance of inquiry can be less obvious, and easier to skip. And it's right here — at this locus between the known and the unknown — where the need to question everything is arguably at its very greatest. So then how could I possibly be asserting that we shouldn't question everything? Have I finally lost my last marble? Is it time to be skeptical of the skeptic? Shouldn't you always? I say this because we live in a world where, in everything we do, we face practical considerations. We must decide where to allocate our resources. Do we spend our energy and attention on this, or on that? By the very necessity of living life and getting through our day, each of us necessarily avoids questioning a million perfectly questionable things. Let's look at an extreme example. OK, extreme example of something we shouldn't question: the basic physical nature of our surroundings. Maybe your desk is a computer simulation. Maybe that next square of concrete on the sidewalk ahead of you is a hologram and you'll fall through it. Maybe there's nothing behind you but emptiness, and as quick as you can whirl around to check, some powerful simulation creates the other half of the room for you to see. Clearly, you would not live a very productive life if you spent every moment doubting the basic nature of everything and contriving clever tests. Your experience living life has taught you that your surroundings are likely to pass every such test, and so you've learned not to bother to question them. And you shouldn't. I'm not claiming they're all real beyond any doubt; I'm simply pointing out that it's generally not worth your time to question. It's ridiculous. Should we question whether the government is spying on our cell phones? Yes, of course we should, because that's a reasonable suspicion for which there is precedent. Should we question whether the government consists of reptilian beings wearing electronic disguises? No, we shouldn't, because that's ridiculous. So let's call this our first test for whether an idea is worthy of inquiry. Is it ridiculous? If it is, then it's not worth questioning, and your energy is better spent on a better problem. Let's take a far more practical example. You're in geometry class, and you're asked to write a proof that one triangle is congruent to another using the side-angle-side postulate. You're expected to assume that this postulate is valid. You're not asked to question the postulate. It's presented to you as a given that you should just accept. Should you? Why? Isn't this exactly the kind of thing we should question, some edict handed down from authority that we are told to embrace without inquiry? A mathematical axiom is something else I would advise that you should not question. Not because it holds some lofty quasi-religious stature, or because it is the dogma handed down from the science cabal; but simply because it's been so thoroughly validated and confirmed that the chances of it being wrong are vanishingly small. It's not worth your time to question. Philosophically, sure, mathematical axioms should all be challenged. Practically? Not so much. And yet this is exactly the pushback I receive so often from so many detractors, who take proven fundamentals and flaunt their questionability as evidence supporting their particular pseudoscience. These people run the gamut, from perpetual motion guys claiming to have overcome the laws of thermodynamics, to Young Earthers whose alternate natural history violates the law of exponential decay. And let's not even get started on the number of fringy cranks who have claimed to have proven Einstein wrong over the years — in most cases it's because Einstein is the only scientist whose name they know, not because mathematical axioms are, in fact, as fragile as houses of cards. Is it possible that our most basic physical laws are wrong? That two plus two does not actually equal four? Certainly it is possible. Are these laws above question for some moral or sacred reason? Certainly they're not. But the chances of them being wrong are so small that your time is probably better spent getting on with the triangle proof than it is trying to prove that the speed of light is not a constant. Let's call this our second test for whether an idea is worthy of inquiry. Is it axiomatic? If it is, then it's not worth questioning, and your energy is better spent on a better problem. But where I hear "Question everything!" the most is in cases where a popular belief runs counter to mainstream science or history. It is the rallying cry of the conspiracy theorist, the revisionist historian, the alternative science crank. They attack science with an ad-hominem against who promotes it rather than what it actually means. 9/11 was an inside job because the government says it wasn't; you can run your car on water because the gasoline companies say you can't; crystals heal cancer because Big Pharma says they don't. And of course, the government, Big Oil, and Big Pharma should all be questioned. Of course they should; they are policy-based organizations. But the questionability of policy-based organizations doesn't mean science findings that happen to work in their favor are wrong. The finding that JFK was killed by a lone gunman has been questioned with a thoroughness that defies description. No worthwhile evidence suggests anything to the contrary. The only remaining support for alternate versions comes from those who are speaking emotionally or ideologically, not factually. Morally; should you question it? Absolutely. Logically; should you question it? Absolutely. The philosophical imperatives of Socrates and Descartes demand that you question it. For every intangible reason that exists, these ideas should be audited and crushed through the wringer of scrutiny, and torn apart and shredded until they've given up every crumb of data. But practically? In the real world? No. You're not going to find anything new. You shouldn't question them, because you're wasting your time. Aspartame is the food product that has been subjected to more testing than any other in history, with never a shred of evidence found supporting the claims that it's poisonous. In theory, a science finding is always open to change and improvement; so in that sense, we should always continue to question the safety of aspartame, as we would bananas or maple syrup. But from a purely practical perspective, the safety of aspartame is as axiomatic as side-angle-side. It has been exhaustively questioned for decades, and further study is — beyond any reasonable doubt — not going to overturn anything. The safety of aspartame is a fine example of something I'd say you shouldn't question; not because there's anything wrong with doing so, but simply because it's a waste of time. It's already been done to death. Is the government covering up alien visitation? Are vaccines harmful? Was the moon landing a hoax? These are questions that have been done to death, and there is nothing new you're likely to learn by questioning them further. Unless your motivation is emotional or ideological, it's time to recognize there's nothing to be gained from continuing to go over our most-trodden ground. Let's call this our third test for whether an idea is worthy of inquiry. Has it already been questioned to death? If it has, then it's not worth questioning, and your energy is better spent on a better problem. So let's recap. We now have three tests you can apply to any concept to see whether you should question it:

If you can answer yes to any of the three, then it's almost certainly not worth questioning. Let the philosophers debate it all day long. But in the real world, questioning everything is neither healthy skepticism nor good science. It's where skepticism crosses the line into paranoia, and where good science turns into grossly inefficient science. If we can all temper our curiosity with reason, we'll find that our inquiry becomes far more productive. And I'll repeat, just so nobody's unclear on my position: No, you should not question everything.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |