|

|

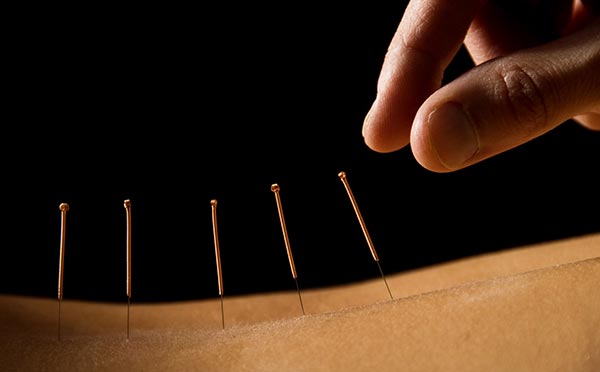

AcupunctureSkeptoid Podcast #431  by Craig Good This ancient Chinese medical tradition stretches back over 3,000 years, the wisdom of the ancients producing medically valid results even today. As in antiquity, slender needles are inserted at precise meridian points on the body and manipulated by a skilled practitioner. Each acupuncture point relates to a specific organ or function in the body, and the practice manipulates the body's energy, or qi to manage pain and treat a host of conditions including allergies, asthma, headaches, sciatica, insomnia, depression, high blood pressure, fibromyalgia, constipation, and even sexual dysfunction. Acupuncture is, in short, a venerable medical miracle. Or is it? Let's cast a skeptical eye at one of the most popular "alternative" medical modalities in the modern world. Exactly how ancient is acupuncture? Not nearly as ancient as you may think. The first clue is right there in the hands of the acupuncturist: Those slender, flexible, stainless steel needles. The technology to make them didn't even exist until about 400 years ago. There are even more historical clues. The Chinese have long kept detailed records. When we examine them we do, indeed, find references to a practice called needling, but the earliest dates to about 90 BCE. The needles from that era were large, and the practice of needling refers to bloodletting and the lancing of abscesses, a treatment nothing like today's acupuncture. Earlier Chinese medical texts, some reaching back to the 3rd century BCE, never even mention it. There's no evidence at all that acupuncture is anywhere near 3,000 years old. No matter. At least acupuncture is Chinese, right? Maybe not. Chinese scholar Paul Unschuld thinks that the practice may have started in ancient Greece, with Hippocrates of Cos, and later spread to China. A fundamental feature of acupuncture, namely the special meridian points where the needles must be placed, can be traced to the medieval Islamic and European ideas of astrology mapped onto the body. This rather obvious link led researcher Ben Kavoussi to call acupuncture "Astrology with needles" He writes: ...for most of China's long medical history, needling, bloodletting and cautery were largely practiced by itinerant and illiterate folk-healers, and frowned upon by the learned physicians who favored the use of pharmacopoeia.Accounts of Chinese medicine first reach Europe in the 13th century. None of them even mentioned acupuncture. Wilhelm Ten Rhijn, writing in 1680, was the first Westerner to reference acupuncture. But what he described bears little resemblance to the acupuncture of today. There was no mention of qi, which is sometimes translated as chi, or any specific points. He spoke of large gold needles that were implanted deep into the skull or womb and left in place for 30 respirations. The first American acupuncture trials were in 1826, when it was seen as a possible method of resuscitating drowning victims. As Dr. Harriet Hall describes it, "They couldn't get it to work and 'gave up in disgust.' I imagine sticking needles in soggy dead bodies was pretty disgusting." Even through the early part of the 20th century nobody spoke of qi or meridians. Practitioners merely inserted needles near the point of pain. In fact, qi used to refer to the vapor arising from food, and the meridians were called channels or vessels, which is part of acupuncture's link to medieval astrology and vitalism. So just when and where did meridians enter the picture, and qi finally become some kind of energy? Enter George Soulié de Morant, who first postulated those ideas in the year 1939. A French diplomat, fluent in Chinese, he became an acupuncture advocate after witnessing its use in a cholera epidemic in China, and later wrote the book Chinese Acupuncture, still considered by many to be a classic work on the subject. He based some of it on histories he translated from the Ming dynasty, which spanned the years 1368 to 1644. Not quite two decades after Morant's book, in 1957, another Frenchman, neurologist Paul Nogier, invented Auricular, or ear, acupuncture, sometimes called Auriculotherapy. Meanwhile, in China, the government attempted to ban the practice by decree in 1822, and in 1929 tried to ban traditional Chinese medicine altogether, because medicine from the West was gaining influence. When Mao Zedong came to power he rescued acupuncture by making it a part of his "barefoot doctor" program. He saw it as a cheap way to provide care to the masses. By the way, Mao didn't believe it worked and would not use it. He preferred doctors. Acupuncture really got popular in America after Nixon's visits to China in the early 70's. Journalist James Reston returned from the trip having famously had an apendectomy while there. Doctors removed it via conventional surgery, and Reston described how acupuncture was used as part of his post-operative pain management. As so often happens, the story eventually morphed into one where acupuncture was the only anesthesia provided during the surgery, even though it wasn't actually used in the operating room at all. His article in the Times was the first most Americans had heard of the so-called "traditional" Chinese medical practice. Of course, the history of acupuncture, while surprising and interesting, has no bearing on its medical effectiveness. The important thing is whether it works or not. While medical science has provided treatments that a mere century ago would have been indistinguishable from magic, it is a messy, imprecise process. Ethical considerations prevent using a treatment on people until it has jumped through several important hoops. Let's view acupuncture through a few of those hoops. PlausibilityWe all commonly apply the idea of plausibility in our lives. If your son tells you that the dog ate his homework, assuming you have a dog, the excuse has at least some plausibility. A dog could actually do that, even if few are known to show that kind of interest in history assignments. If he claims that dinosaurs broke in and stole it, you would likely find that story somewhat less plausible. Consider a mature, well-studied aspect of science-based medicine, such as treating minor pain with aspirin. Even before aspirin was isolated, people had learned that chewing on the right tree bark made their headaches go away. Since aspirin is an actual chemical, and chemicals can have an effect on the body, it is a plausible treatment. Contrast this with acupuncture, which is loosely based on a hodge-podge of historically dubious beliefs. Remember how some believe acupuncture is ancient? Even if it were that old, its age would be a hindrance, not a help. All of the ideas behind it are pre-scientific notions, as outdated as "balancing the humors". The so-called "energy" of qi, so recently coined, is a modern expression of ancient vitalism. The meridians are, as we already saw, tied to astrology, yet another pre-scientific implausibility. What's more, nobody can seem to agree on how many meridians there are or where they should be. At one point acupuncture charts mapped 365 points, based on the number of days in the year, not on anatomy. But today acupuncturists claim to have "discovered" some 2,000 meridian points, pretty much guaranteeing that you could glue a needle to a dart, chuck it at the patient from across the room, and hit one of them. Are there 9, 10, or 11 meridians? Nobody seems to know. It doesn't matter, because no research has found evidence (PDF) for the existence of acupuncture points, meridians, or qi. Acupuncture's plausibility has more holes in it than one of its long-suffering patients. EfficacyPut simply, efficacy answers the question, does it work? This is what we want from our medicine: real results. Acupuncture has been studied perhaps more than its poor plausibility would merit. Supporters point to the studies which show that acupuncture works, and ignore those that don't. When evaluating studies there are all kinds of things to consider. Are the putative "researchers" part of an organization which promotes the modality under test? What's the methodology of the study? Did they use proper blinding and placebo controls? It's a big subject and we don't have time to go into detail right now, but here are some things to consider. First, where was the study done? In 1998 the researchers Vickers, Harland, and Rees performed a systematic review of controlled trials and discovered a pattern. Research conducted in certain countries was uniformly favorable to acupuncture; all trials originating in China, Japan, Hong Kong, and Taiwan were positive, as were 10 out of 11 of those published in Russia/USSR. ...Of trials published in England, 75% gave the test treatment as superior to control. The results for China, Japan, Russia/USSR, and Taiwan were 99%, 89%, 97%, and 95%, respectively. No trial published in China or Russia/USSR found a test treatment to be ineffective. But careful, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trials of acupuncture have been done. Some of them are quite clever. A special sheath can be made that either contains an acupuncture needle that will enter the skin when pressed, or a toothpick that will just lightly poke the skin. Neither the practitioner or the patient knows which is which. The results? It doesn't matter where you stick the needle, and it doesn't even matter if you stick the needle. Acupuncture works no better than not doing acupuncture. Indeed, the higher quality the study, the more acupuncture appears to work no better than placebo. Now, placebo is widely misunderstood. What it really represents is the noise floor of the experiment. Subjectively experienced symptoms such as pain often come and go on their own. Many disease processes, even cancers, can spontaneously remit. This is the background noise that an effect must be judged against. Picture yourself standing at the beach with the roar of the waves in your ears. You are listening to hear if someone is speaking behind you. If the voice isn't loud and clear enough to be understood over the background, or noise floor, of the surf, then you can't conclude that the speaker is even there. When a clinical trial concludes that the modality being tested performs "no better than placebo" that's just science's cautious way of saying it doesn't do anything. Or, if it does, it's too quiet to hear over the sound of the waves. So why do so many people report feeling better after acupuncture? There are many plausible explanations. Contrasted to the rushed, sterile atmosphere of the typical doctor's office, acupuncture is often performed in a comfortable, relaxing atmosphere. Soothing, personal attention is known to lower stress. A nice massage is likely to be just as effective. Some of the positive trials resulted from sessions where, after the needles are inserted, wires are clipped to them and a small electric current is applied. Yes, this can actually reduce muscular pain, but it isn't acupuncture. It's a known treatment called TENS, or Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation. Any efficacy using acupuncture is more plausibly linked to what happens around acupuncture than to the acupuncture itself. SafetyThe ancient Greeks didn't have the science-based medicine we now enjoy, but they could clearly see that a doctor's first duty is to "do no harm". Even if a treatment is plausible and effective, there's not much point if it's going to injure or kill you. One of the biggest issues medical studies need to address, then, is safety. When you and your doctor discuss a proposed treatment you both make some sort of risk/benefit analysis. If you have a life-threatening disease it might be worth trying a higher risk treatment, but for minor conditions you will usually go for lower risk. And there's always some kind of risk. This is just as true for acupuncture. While its overall safety, at least as typically practiced in the United States, is pretty good, any time someone is piercing your skin with sharp tools there can be serious complications. Canadian athlete Kim Ribble-Orr had her lung collapse when the massage therapist treating her for headaches decided to try the acupuncture that he learned on weekends at the local university. Collapsed lungs are considered a "rare but well-documented" side effect of acupuncture. Other documented risks include the the transmission of hepatitis C and hepatitis B. But, as with other so-called "Complementary and Alternative Treatments", the greatest risk may be to those who avoid science-based medicine in favor of an ineffective treatment. On the What's the harm? website you can read of hundreds of cases where patients have been damaged, sickened, or even killed by the decision to embrace alternative therapies like acupuncture rather than real medicine. Medicine is a complex field, and little matters more to us than our health. When it comes to acupuncture, a modern twist on medieval misconceptions with no real benefits, and rare, but serious complications, it pays to remain skeptical and insist on plausibility, efficacy, and safety. By Craig Good

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |