|

|

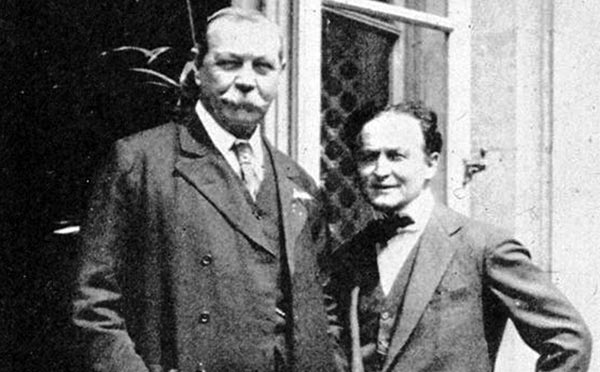

Harry Houdini and Sir Arthur Conan DoyleThe clash between the champions of scientific skepticism and supernaturalism. Skeptoid Podcast #430  by Brian Dunning Harry Houdini (1874-1926) was best known as the world's most famous magician during his lifetime, and also as a tireless debunker of false mediums and dishonest claims of profit-driven supernaturalists. He followed a simple strategy, one that's the fundamental basis of the scientific method: Work hard to falsify all new hypotheses, and maintain a mind open to all new evidence. Sadly for Houdini, this meant testing what could have been one of the most important personal relationships to the history of public understanding of science. Much has been made of the friendship between Houdini and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. As the creator of Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur would seem to have been a man of science and rational thought, but he was a lifelong steadfast believer in the supernatural. In fact, it was something that was at the forefront of his attention much of the time. One of the most telling events in Sir Arthur's career came when he was a member of the Society for Psychical Research, which is often criticized for being composed mainly of true believers in the paranormal, and not all that interested in objective research. In the 1920s, Sir Arthur led a mass resignation of 84 members of the Society, on the grounds that it was too skeptical. The staunchest of the resignees joined the Ghost Club, of which Sir Arthur was a longtime member. The Ghost Club made no apologies for being fully dedicated to the supernatural as an absolute fact. In addition, Sir Arthur's wife, Lady Doyle, was a medium who often conducted séances appearing to be in communication with the dead, and Sir Arthur was absolutely convinced of the reality of her ability. Despite a radical difference of opinion, Houdini and Sir Arthur managed to keep their friendship alive for some years, each often writing to the other of their mutual respect, their agreement to disagree, and the value of honesty and integrity in one's own beliefs — neither man ever doubting the other's sincerity; at least for a while. In the spring of 1922, Houdini invited Sir Arthur to the home of his friend Bernard Ernst, a lawyer in New York, in an effort to show him that even the most amazing feats of mediums could be accomplished by skilled — albeit earthly — trickery. He had good reason to sway Sir Arthur if he could; Sir Arthur was passionately engaged in promoting the supernatural to his vast worldwide audience, a public disservice if there ever was one, as honestly intentioned as it was. Houdini prepared a magic trick, one that's familiar to any practitioner of the art. He had Sir Arthur go outside in private and write a simple note that there's no way Houdini could have seen; and then upon his return to the room, Houdini had a cork ball soaked in white ink magically roll around on a slate and spell out the very note Sir Arthur had written. Sir Arthur was aghast. Houdini wrote him:

Sir Arthur evidently did not. He responded by inviting Houdini to his own home on June 17, 1922 so that his wife, Lady Doyle, could convince Houdini of the reality of the supernatural by giving Houdini a reading from his deceased mother. In the ensuing séance, Lady Doyle, apparently channeling Houdini's mother, wrote the following letter:

A fairly generic letter, if there ever was one. Houdini left unimpressed. So unimpressed, in fact, that in correspondence to the New York Sun answering a $5,000 challenge by the General Assembly of Spiritualists, Houdini wrote:

Sir Arthur could hardly believe what he read, as he'd just personally shown Houdini proof via a letter from Houdini's own mother. His faith in his friend's honesty unsettled, Sir Arthur wrote:

Houdini shot back:

But the hurt was too deep. In 1923, Harry Houdini agreed to join a committee formed by Scientific American magazine at his own urging, to offer a total of $5,000 in prizes for any medium that could pass the committee's tests. Houdini imposed strict conditions under which he would serve, intended to allow no margin for error. Upon his participation in the committee becoming known, Sir Arthur could no longer control his disillusionment with Houdini and wrote:

The friendship dissolved completely into public threats of lawsuits, when Houdini revealed the cheating methods of one applicant for the prize whom Sir Arthur had previously endorsed. Undeterred by the personal loss, Houdini continued challenging and defeating mediums for the rest of his life. Even as his fame increased for his unfathomable escapes and stage acts, so grew the loathing for him among the psychic and medium communities whose cheats he continued to reveal. After Houdini's death in 1926, Sir Arthur published The Edge of the Unknown about his life experiences with spiritualism, and he dedicated an entire chapter to his thesis that Houdini actually had supernatural powers, but knowingly lied about them, pretending all his skills were of earthly origin.

By the time of his death, Houdini had forged a dozen compacts with trusted friends to contact him after they died if they were able, but none ever did; they had arranged secret handshakes which no medium ever reproduced.

His beloved wife, Bess Houdini, had held annual séances, as they'd planned, to reach Harry in the hereafter. None of the attempts were successful. The code word Harry and Bess had agreed upon, Rosabelle believe, never emerged in any of the séances, and after a decade she finally doused the candle that burned beside a picture of Harry in their home. "Ten years is enough to wait for any man," said Bess. Soon her own health failed her, and in 1943 she boarded the Santa Fe Chief train in Los Angeles to head home to New York, but died on board the train only a few hours into the journey. The newspaper ink was still drying in the final interview she gave, in which she declared:

PS: Before you email and tell me that spiritualist Arthur Ford did receive the Rosabelle believe message in 1929 and that Bess confirmed it was from Harry, it should be noted that the message was never secret. It was from a song that Harry and Bess had sung during their performances together and was engraved in Bess' wedding ring. From what we know of Bess, it seems clear that she never took the ten years of séances seriously and only did them for publicity purposes; the final one was actually on the rooftop of the Knickerbocker Hotel in Los Angeles and was widely attended by the media, and the blowing out of the candle was a central moment. The 1929 stunt with Arthur Ford was probably to gain notoriety for a lecture tour.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |