|

|

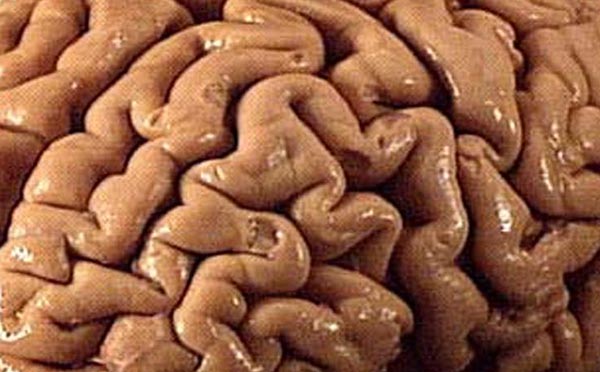

Left Brained, Right Brained, or Hare Brained?Skeptoid Podcast #418  by Brian Dunning Perhaps the most pervasive popular belief that people associate with neuroscience is the idea that we all tend to be either left-brained or right-brained, based on traits like creativity or analytical ability. It's well known that certain brain functions are localized in various parts of the brain, so it would seem to make sense that some of our individual strengths and weaknesses can be quantified based on brain hemisphere dominance. Quite a few companies even sell products intended to analyze your brain sidedness, promising a variety of personal development benefits. But is this belief — so widely held — good science, terrible science, or some mixture of the two? Once in college, I took an Honors Colloquium class that was supposed to expose us to a wide variety of ideas and experiences. It was taught by three professors who were presented to us as being the smartest, most well-rounded guys on campus. One of our exercises was to take a test that was supposed to reveal our brain sidedness. The questions were similar to what you might get in a personality test, asking about whether you prefer math or art, privacy or crowds, planning ahead or working on the fly. Some days later we each received our results: a two-axis radar chart, showing a skewed diamond with its left and right corners representing the levels to which we depended on our left brain or right brain, and the top and bottom corners showing the degree to which we depended on our anterior or posterior parts of our brain. It was explained to us that these results could be used to help us self-assess our aptitudes at various skills. Would we be good at sales, leadership, or education? What areas of ourselves could we work on to improve ourselves? What kind of value could we add to an organization with our particular brain map? Most students had crazily shaped radar charts that showed a strong dependence on one brain area or the other. The horizontal axis had a range of zero to 120 on both sides. We all thought that anyone who had a chart exceeding 100 on either side must be extraordinarily talented according to the popularly believed norms: if you were over 100 on the left you were a math or analytical genius; if you were over 100 on the right you were the next Mozart or Rembrandt. I was very proud that mine was the only one that was symmetrical, 94 on both sides; but after later reflection, I recalled that many of the questions had to do with the classes we were taking. At the time my idea was to double major in computer science and film directing, so I'd given a lot of answers that indicated I was both analytical and creative. I hadn't had much experience in scientific skepticism at that point, but if I had, I might well have realized that the test was grossly unscientific and relied completely on self-reported answers that might have changed from one day to the next, depending on mood, terminology, context, and many other variables. Looking at the same test now, I realize that was only the tip of the iceberg. Brain sidedness as a predictor of either preferences or aptitudes is unscientific for a very good reason: it's virtually entirely wrong. Let's go back to that popular public assumption that the left brain is analytic and the right brain is creative, upon which so many of the questions in my Honors Colloquium test focused, and upon which the whole class based the entirety of their analyses of their test results. The natural inference is that people whose left brains are dominant must be good at analytical skills, and people whose right brains are dominant must be good at creative skills. The reverse would also be true: If you are a mathematician or engineer, we might deduce that you are left-brained; and if you're an artist or poet, that you're right-brained. Where did this idea come from? It appears to have its original roots in the work of Dr. Roger Sperry, who worked with epileptic patients in the 1960s and 1970s. One extreme form of treatment was to sever the corpus callosum, which is the major connection between the two brain hemispheres. He was a co-recipient of the 1981 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine for his split-brain research, which was the seminal work that taught us that certain functions in the brain are lateralized, that is, concentrated in one hemisphere or the other. An interesting part of the work Sperry did with one of his collaborators, Dr. Michael Gazzaniga, was to find out what would happen to patients whose corpus callosums (corpora callosa if you are pedantically inclined) were severed. In short, so long as patients had both eyes and both hands available to perform tasks, they were generally all right. But when only one hand was allowed to feel an object, and only one eye was allowed to read a certain word, a lot of fascinating things happened. Patients reported seeing the word if they saw it with their left eye, but not if they saw it with their right eye. In fact, if shown the name of an object with their left eye (interpreted with their right brain), their left hand could identify and find the object. But then when the patient was asked about it (requiring the left brain), they were unable to say what word they'd been shown and unable to explain why they were holding it. Spoken language, it seemed, was centered in the left side of the brain; while the ability to analyze and comprehend was centered in the right. However, pop-culture psychology decided to misunderstand and exaggerate this. Ever since then, there's been this popular notion that people with strong tendencies toward analytical or artistic pursuits must be dominant in one hemisphere or the other. The idea can be traced back to two facts. The first fact is that, as Sperry and Gazzaniga demonstrated, many brain functions are localized. Just about any given function is centralized in a particular brain region. Two of the most familiar are language, which is localized mainly in the left hemisphere; and facial recognition more in the right hemisphere. Today we can verify these types of observations which technologies such as fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) which shows where blood flow is greatest in the brain at a given moment, a technology that was unavailable in Sperry's day. If someone is working on math problem, we'll see more activity in a different part of the brain than we would if they were looking at a painting. The second fact is that people are either left handed or right handed. For the most part, the left side of the body is controlled by the right side of the brain, and the right side of the body is controlled by the left. A right handed person working a complicated task with his right hand will show more fMRI activity in his left hemisphere, and vice versa. So it stands to reason — apparently — that a leftie will tend to be more skilled at activities that are lateralized in the right part of the brain, such as composing music, and a rightie will tend to be more skilled at things like computer programming. This has largely given rise to the myth that left handed people tend to be more creative: better artists, better musicians. So what's the problem with these two facts? Despite that they're both true, why are they not reasons that people are left brain dominant or right brain dominant? Although brain functions can be lateralized, the brain as a whole is a single unit. The corpus callosum is there for a good reason; the brain hemispheres must be linked to work together, just as your computer's internal components must be linked by cables. The fact that certain functions tend to be lateralized has nothing to do with any "dominance" of one hemisphere or the other in people with particular skills. And although left-handed and right-handed people will tend to show differing levels of activity in their hemispheres when performing certain tasks, it's not necessarily a requirement. An important feature of the brain is an ability we call neuroplasticity, which is its power to relocate certain functions when needed. Sometimes brain injuries can destroy a region. Neuroplasticity means that other parts of the brain can often re-learn abilities (to varying degrees) that used to be localized in the damaged region. A left-handed person need not necessarily become right-handed after suffering an injury in the right hemisphere. A familiar example of neuroplasticity is the ability of stroke victims to regain functions such as speech, agility, and even symmetrical control of facial muscles after losing those abilities to the brain damage caused by their stroke. Notably, the majority of patients who undergo perhaps the most frighteningly-named surgical procedure, the hemispherectomy, are able to live relatively normal lives (at least when the procedure is done earlier in childhood; older patients don't often fare as well). Memory, personality, and aptitudes are usually unchanged after the procedure. Manual dexterity and vision are usually heavily impaired on the side opposite the hemisphere that is removed, but that's the result of the loss of certain anatomical structures. Studies of hemispherectomy patients have shown no correlation between which half was removed and the patients' language abilities, analytical abilities, and other skills we tend to relate to brain sidedness. Neuroplasticity is the basic explanation for why personalities and aptitudes are not correlated with any sort of hemisphere "dominance"; to the neurologist, it's essentially a meaningless term. Nevertheless, you will find that any number of companies sell tests claimed to help you better understand your aptitudes and potential based on determining whether you're left-brained, right-brained, anterior-brained, posterior-brained, or just about anything else. Companies promise to improve your business performance and help you identify areas for improvement. One even provides a 60-page report including an 8-axis radar chart, your ranges of "analysis, expression, drive, and stability", and the word "neuroscience" is peppered throughout the marketing materials and products of these companies. In fact it's supported by no evidence at all, and no legitimate neuroscience pretends to measure these traits. Dr. Steven Novella summed it up aptly in his final sentence of a 2008 article in Neurologica:

Neuroscience is, at once, one of the most complex and nascent fields in current research. Brains are perhaps the most complicated and nuanced structures in nature. Send not thy money to those who claimed to have it all figured out. As a neurologist at the University of Arizona told me after reading a draft of this episode, brain tests such as brain sidedness, Myers-Briggs, etc., are just as "science-based" as the average Which Game of Thrones Character Are You quiz on Buzzfeed.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |