|

|

The Fate of Fletcher ChristianSkeptoid Podcast #284  by Brian Dunning The mutiny on the Bounty is perhaps the best known of all stories from the era of wooden ships. Fletcher Christian, the infamous officer responsible for the affair, is believed to have died on Pitcairn Island, where he and the other mutineers took refuge. Yet some say his death was faked, and he did in fact make it back to England. Today we'll point the skeptical eye at these stories, and see if we can learn for certain where Fletcher Christian made his final atonement. The basic story of the Bounty is not only well known, it's well documented and not in any meaningful doubt. In 1789, the small British naval ship left the island of Tahiti with a cargo of breadfruit plants. Three weeks later, its discontented crew, led by sailing master Fletcher Christian, mutineed against Captain William Bligh. Bligh and the loyal crew members were set adrift in the Bounty's open launch, in which they ultimately made it to safety, and made knowledge of the mutiny public. Christian and his crew of 24 — eighteen mutineers, four loyalists who couldn't fit in Bligh's launch, and two neutral men — sought refuge for several months in some of the neighboring islands, but upon finding the natives too unfriendly, they returned briefly to Tahiti. Sixteen of the men remained there, leaving only eight aboard the Bounty; barely enough to sail her. And so, one night when the mutineers' women and some other natives happened to be on board, they set sail unexpectedly, effectively kidnapping the Tahitians. And thus was the founding population of Pitcairn Island established: eight British sailors, six Tahitian men, eleven Tahitian women, and one baby. These events are known from the accounts of the sailors who remained on Tahiti, including the four loyalists, who were either captured by or rejoined the British navy when the ship Pandora was dispatched to find them. From that point onwards, the fate of the Bounty is more thinly documented. Fletcher Christian took his crew to Pitcairn Island because he knew from the British charts that its position was not precisely known, so they'd have a fair chance of evading capture. When they arrived, the Bounty was scuttled, both to avoid advertising their presence and to prevent anyone from leaving the island and possibly raising the alarm. We know for a fact that the Bounty was sunk because its remains have been found. Without any reasonable doubt, Fletcher Christian left Tahiti aboard a ship that went to Pitcairn Island and nowhere else. No other ship of any nation reported encountering them en route. One of the mutineers who elected to remain on Tahiti was Peter Heywood, a close friend of Christian's. Along with the others, Heywood was captured by the Pandora in 1791 and returned to England. He was court martialed and sentenced to hang; but his was a family of wealth and influence, and Heywood received a pardon. Heywood returned to service in the navy, rose through the ranks, and had a successful career as a captain. Heywood was to play a pivotal role in the theories of Christian's alleged return to England. It was reported in 1831 by Sir John Barrow, an acquaintance of Heywood's, who detailed the following account in his book The Mutiny and Piratical Seizure of HMS Bounty:

Although Heywood's is the only reliably documented account of anyone actually encountering Fletcher Christian in England after the mutiny, there was already something of an urban legend at the time. Barrow also wrote:

In 1797, eight years after news of the mutiny reached England, Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote his poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, which in some circles was believed to be loosely based on the life of Fletcher Christian, prompting speculation that Christian must have been available for Coleridge to interview. Coleridge's colleague William Wordsworth had been a childhood classmate of Christian's. When Christian was tried in absentia for the crime of piracy, he was defended by his brother, the lawyer Edward Christian, and Wordsworth joined in his defense. So well known (or at least well believed) was the association of Coleridge and Wordsworth with Christian that at least one author, C.S. Wilkinson, proposed in his book The Wake of the Bounty that the two poets might have collaborated to have somehow brought Christian back to England. No evidence of this has ever been offered, but it remains one of the most popular rumors about Christian's fate. Could the man Peter Heywood chased in Plymouth actually have been Fletcher Christian? For this to be possible, Christian would have had to have found some way of leaving Pitcairn Island after his known arrival there in 1789, and no later than when the island was visited by the American seal hunting ship Topaz in 1808. On that day, three young men who appeared to be Pacific Islanders paddled out to the Topaz in a Tahitian style canoe, and astonished its captain, Mayhew Folger, with their friendliness and perfect English. According to Folger's logbook, the three young men invited him ashore to dine with the man they called their "father", Aleck. Aleck turned out to be an Englishman named Alexander Smith, and was the sole surviving Englishman on the island. Aleck identified himself as one of the crew of the Bounty, and gave Folger the general facts. He also explained that the six Tahitian men, whom they had kept as slaves on the island, rose up and murdered all of other mutineers, including Fletcher Christian. Aleck and the women then managed to put all six of the Tahitians to death, leaving them in the current situation. Folger was ultimately able to deliver this report to the British navy, along with his statement of Aleck's character:

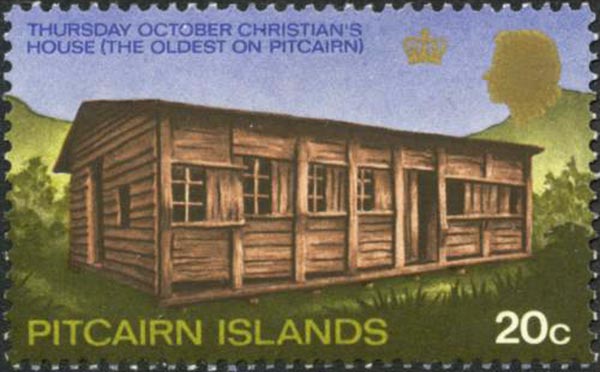

Folger was satisfied that there were indeed no other Englishmen living on the island. Similar circumstances were discovered six years later in 1814 when two British ships, HMS Briton and Tagus, visited. This time the leader of the young men identified himself as Thursday October Christian, the 25-year-old son of Fletcher Christian. By Thursday's own account, his father had indeed been killed on the island. Captain Pipon of the Tagus wrote a detailed account of their days spent on the island, and of what they learned. Alexander Smith, it turned out, was a fake name, and Aleck was actually John Adams, an Able Seaman who denied having had any part in the mutiny (contrary to what had already been learned from Captain Bligh and his loyalists). Perhaps having learned from Folger that there was no longer any great dragnet to catch the mutineers, Adams was much more forthcoming with Pipot than he had been with Folger. He showed the detailed log the islanders had kept all those years, and it included the true fates of the Englishmen and the Tahitians. Disputes over women, authority, and slavery had torn the group apart, with murders having taken place on both sides. Fletcher Christian had been killed by two of the Tahitians on the island's bloodiest day in 1793 on which four of the Englishmen died. Christian was survived by his Tahitian wife Maimiti and three children: Thursday, Charles, and Mary Ann. Thursday, the oldest, was not quite three years old when his father was killed, so Adams (and one other who had died in the interim) were the only Englishmen any of them ever really knew. Maimiti witnessed her husband's death and later recounted it in great detail. This was the true history of Pitcairn Island's colonists according to all of them who were ever asked. For Fletcher Christian to have been the man that Peter Heywood chased, he would have had to survive on the tiny Pitcairn Island undetected by his own family for 15 years, then sneak on board the Topaz, somehow persuade its captain and crew not to reveal his existence, then found his own way back to England (halfway around the world) within the year while the Topaz and its crew were held by Spanish authorites on Juan Fernandez Island for several months on an unrelated matter. Is that string of improbabilities really more likely than Heywood was simply mistaken about the identity of a man whose face he saw only once in a quick glance, and even then only in a secondhand report? The escape of Fletcher Christian, or any other larger-than-life character from history, makes for a fine story, but not necessarily a true one.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |