|

|

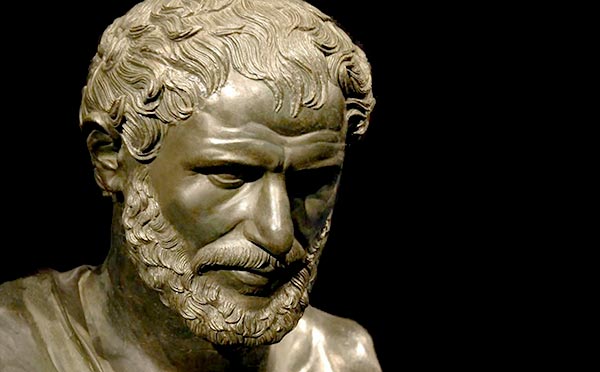

Zeno's ParadoxesGreek philosopher Zeno apparently proved that movement was impossible with a few simple paradoxes. Skeptoid Podcast #267  by Brian Dunning Even if you think you haven't heard of them by name, you'll recognize them. The most familiar of Zeno's paradoxes states that I can't walk over to you because I first have to get halfway there, and once I do, I still have to cover half the remaining distance, and once I get there I have to cover half of that remaining distance, ad infinitum. There are an infinite number of halfway points, and so according to logic, I'll never be able to get there. But it's easy to prove this false by simply doing it, which we can all do. So we have a paradox, a contradiction, something that must be true but which, clearly, is not. Does there exist a solution which adequately addresses the contradicting phenomena? Some say there is; some say there is not. Zeno of Elea was a Greek philosopher, born about 490 BCE, and was a devotee of Parmenides, founder of the Eleatic school of thought in what is now southern Italy. Zeno survives as a character in Plato's dialog titled Parmenides, and from this we know what the Eleatic school was about and where Zeno was coming from with his paradoxes. Parmenides taught (in part) that the physical world as we perceive it is an illusion, and that the only thing that actually exists is a perpeutal, unchanging whole that he called "One Being". What we perceive as movement is not physical movement at all, just different interpretations or appearances of the One Being. Personally, I think they smoked a lot of weed at the Eleatic school, but Zeno was into this and came up with his paradoxes in order to support Parmenides' view of the world. Zeno's paradoxes were intended to prove that movement must be impossible, therefore Parmenides must be right. He is believed to have developed a total of about nine such paradoxes, but they were never published. The most famous and interesting are his three paradoxes of motion:

Zeno's paradoxes are often touted by some people as evidence that physics or science are wrong. If an ancient Greek philosopher can describe a simple situation, which our intuition tells us is obviously correct, it's easy for us to assign it more significance than we do the confusing jumble that is modern science. Why should we listen to Einstein, who gives us a lot of unfathomable equations, when Zeno's elegant fables prove that the physical world is not as science tells us it should be? Given this line of reasoning, it's hardly surprising that Zeno has become something of a darling to some New Age supporters of a spiritual, not a physical, universe. Famously, upon hearing the paradoxes, a fellow philosopher named Diogenes the Cynic simply stood up, walked around, and sat back down again. My kind of guy. His response may have been glib, but it elegantly refuted Zeno's claim. At least, it refuted the physical implications of the claim, it did not address the philosophical aspects; nor did it provide the mathematical solutions. Zeno's paradoxes are an interesting intersection between mathematics and philosophy. Mathematically, it's trivial to calculate exactly when and where Achilles will overtake the tortoise, but the philosophical argument remains (apparently) intractable. Bertrand Russell described the paradoxes as "immeasurably subtle and profound". So philosophers have come up with some pretty interesting efforts to try and resolve this. One such tactic concerns the Planck length, which is the smallest possible unit of length within the Planck system. Planck units are all based on universal physical constants, such as the speed of light and the gravitational constant. Philosophically it's reasonably accurate to describe the Planck length as a quantum of distance, the smallest possible unit. This means that there are a finite number of Planck lengths (albeit a staggeringly large number of them) along the racetrack of Achilles and the tortoise, and between Homer and the bus stop. There cannot be an infinite number of points, and so Homer will eventually be able to arrive. However, while this sounds like it might elegantly solve the paradox, it doesn't. It's not possible to force a quantum solution onto a geometric problem. A simple illustration of why this is so is to imagine a very small right triangle with its two equal sides each of one Planck length. The hypotenuse would have to be √2 Planck lengths, which is not possible. Planck doesn't apply here. Despite efforts to conclude otherwise, we are dealing with infinities here. Or... are we? Intuitively, we understand 0.9 (0.9999999...) to be a value that forever approaches 1 but never quite gets there. This is fine as a concept and a thought experiment, but it is mathematically wrong. 0.9 does in fact equal 1; they are simply two different ways of writing the same value. It's easy to prove this to most people's satisfaction by dividing both values by 3. Both 1 ÷ 3 and 0.9 ÷ 3 equal 0.3, therefore both are equal to each other. Another way of looking at it is to consider the fraction 1/9, which is equal to 0.1. 2/9 is equal to 0.2, and so on, all the way up to 8/9 = 0.8 and 9/9 = 0.9, and we all know that 9/9 = 1. When we divide the number 1 into 9 equal slices, that top slice goes all the way up to exactly 1, a finite and reachable number. If this spins your brain inside your skull, realize that you already accept many other interpretations of the same idea. Consider any other number whose decimal value is an infinite repeating series, say 3/7. It equals 0.428571 and we all accept that it equals 3/7, not "a number approaching 3/7 but that never quite gets there." It's two ways of writing the same thing. It's the same concept when Homer takes his final step and places his foot down, completing his journey to the bus stop. He did not take a journey of infinite length. We can write an equation that describes how his final step consists of an infinitely reiterating series of smaller and smaller fractions, just as Zeno said:

We in the brotherhood call this an absolutely converging series, and contrary to Zeno's understanding, it equals 1. Another popularly proposed solution, particularly for the fletcher's paradox, involves time and speed. Zeno, charges his critics, only considered the distances and geometry involved; and since he left time out of his paradoxes completely, he also excluded speed, since speed is a function of distance and time. When a body is in motion, its position is always changing. Motion is fluid, it is not a ratcheted series of jumping from point to point. Consequently, at any given moment in time, a moving body has no single exact position. Zeno's conjecture, that the arrow is always frozen at some point, cannot be observed, reproduced, or computed, since that's not the way things move. Imagine taking a photograph of a moving object. There will always be some motion blur. No matter how fast is the shutter of your camera, even infinitesimally fast, there will always be some tiny amount of blur. There is no such thing as a moving arrow frozen in time. Similarly, Zeno's computation that Achilles will never catch the tortoise also omits time. Zeno's premise assumes that each segment of the race, wherein Achilles advances to the tortoise's previous position, takes some amount of time; and since there is an infinite number of such segments, it will take Achilles an infinite amount of time. This is also wrong. As the physical length of each segment decreases exponentially, in a converging series, so does the time it takes Achilles to traverse it. Achilles' time to catch the tortoise is represented by a converging series that equals a finite number.

So to summarize Zeno's paradoxes, they're basically word games that play upon an easily misunderstood mathematical concept. There is no paradox, because Zeno's math was wrong.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |