|

|

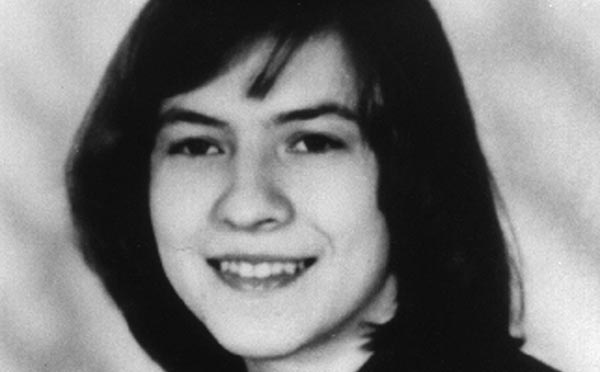

The Exorcism of AnnelieseSkeptoid Podcast #248  by Brian Dunning It doesn't just happen in the movies. Throughout the centuries and in all countries, the faithful have practiced exorcism. It's a religious ritual intended to drive away demons who are possessing a victim's body. Its basic premise — that any such thing as demons or demonic possession even exist — places it outside the bounds of what can be tested or evaluated, let alone proven. But this has not stopped it from being employed in life-or-death situations: Medical emergencies entrusted to prehistoric superstition. Can exorcism truly treat severely disturbed individuals? This was the question with Anneliese Michel, a young Bavarian woman born in 1952. Anneliese was raised in a profoundly devout Catholic home; three of her aunts were nuns and her father had studied to become a priest. But the Michel home had a profane secret: An illegitimate daughter, Martha, born four years before Anneliese. Martha died of kidney trouble when Anneliese was still a child, and compounded with the shame of the illegitimate birth, it rocked the pious family to its core. Anneliese performed constant penance for her sinful mother. The family turned to fringe extremist Catholic groups, forging their own form of deep religious piety. Anneliese's upbringing was one quasi-Catholic rite after another, a constant atonement for the sins of others. At the age of sixteen she began having epileptic seizures. For the next few years, she was in and out of psychiatric hospitals, on and off of a half dozen antipsychotic and antiepileptic drugs, and her behavior spiraled worse and worse. Anneliese became obsessed with atonement and ritual, but it went much further than that. She reported visions of demonic faces and panicked and snarled at sacred images, and the seizures continued and became more bizarre. After exhausting all the medical options, the Michel family turned to the church for help. Over the final year of her life, Anneliese received no medical care (at her own demand) and was put through sixty-seven exorcism sessions, as codified in Roman Ritual. Two priests, Ernst Alt and Arnold Renz, grappled with her demons and recorded forty-two of the sessions on tape: Some half-dozen or more demons within Anneliese spoke, and even identified themselves. The Biblical figures Lucifer, Cain, and Judas were there, as were the historical figures Emperor Nero, Adolf Hitler, and others. Daily she did hundreds of genuflections, dropping to her knees until the ligaments were permanently debilitated. She had open sores all over her body. She scratched herself and bled. Her mouth and nose were raw, her eyes deeply bruised, her hair shredded. She was unbathed and stank horribly. She urinated on the floor and licked it up. Always her voiced growled back at the tormenting priests. She refused food and drink and became a scrawny, wild creature in her own home. Her own family was afraid of her. The thinner and smaller she got, the more like an animal she became. And then, one morning, the house was silent. The demons were gone. Anneliese lay in her bed, dead. She weighed 31 kg, or 68 lbs. She was 23 years old, a ragged, crazed stick-figure caricature of what she had once been. The cause of death was starvation and dehydration. To exorcise (from the Greek exorkizein) means to adjure, to make a formal command, which must be followed by oath of obedience. The exorcist thus commands the possessing entity to take an oath that they will leave the host body. The practice probably predates written history. Songs for charming demons away are recorded in the Book of Psalms and in the Dead Sea Scrolls dated from some two thousand years ago. Various forms of exorcism have been practiced in virtually all cultures for as long as we have history. Today doctors can look at cases like Anneliese, and though we cannot make a reliable diagnosis without an examination, it seems clear that she suffered from a variety of conditions including dissociative identity disorder (formerly called multiple personality disorder). It's usually comorbid with other psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia, from which Anneliese probably suffered as well; and chronic stress is indeed one potential cause of her epileptic seizures. Although the psychiatric profession of the day had not been able to cure her conditions, it probably controlled them to some degree; as she didn't die until she stopped all medical treatment. Belief is a key component of perceived possession and exorcism. If all parties believe that the sufferer is possessed, going through the motions of an exorcism may indeed solve the problem in some cases. And this is a serious problem, because that simple fact can be used to defend the practice; which sometimes results in preventable death. After Anneliese's death, some within the Catholic church made an almost scientific effort to reform church laws governing the use of exorcism. When an exorcist speaks imperatively to the demon, instead of to the patient (to say "I command thee, unclean spirit," or some such thing), it confirms the patient's belief that they are indeed possessed by a demon. This confirmation by an authority makes the psychological problem much worse. Aware of this complication, a commission of conscientious German theologians petitioned the Vatican in 1984 to ban this part of the ritual. It took 15 years for the Vatican to render a decision. When they finally did revise the exorcism formula in 1999 (the first time it had been reviewed since the 17th century), it still allowed for exorcists to directly address the alleged demon. Thus, the Catholic exorcism rite remains contemptuous of basic ethics and any pretense of considering the patient's welfare to be important. The commission had the additional motivation for reform when Anneliese's parents and both Alt and Renz were charged with negligent manslaughter for failing to call a doctor. During her final days, Anneliese's internal organ shutdown was probably irreversible, but a week before she could have been saved by even the simplest medical care. Recognizing that her parents had tried for many years to give every possible type of care for her episodes, the prosecution asked only for a fine for the priests and a guilty verdict but no punishment for the long suffering parents. Before the trial, the parents had their daughter's body exhumed, based on a tip from a nun who claimed that she saw Anneliese's body was incorrupt in a vision. If true, it would confirm the supernatural nature of the case, proving that the exorcism was indeed the proper course of action. When the casket was opened, she was found to be decomposed as expected. The court found all four defendants guilty, but went further than the prosecution asked and gave suspended prison sentences plus three years probation. The Michels remained convinced that they'd done the right thing. Of course, Anneliese was not the only victim of exorcism. The excellent website WhatsTheHarm.net lists over a thousand such cases, most from the recent decade, and most from Western countries. It is not ancient history and it is not limited to developing countries. Hundreds of professional exorcists walk among us, today, seeking critically ill psychiatric patients upon whom they can shout charms and sprinkle water. Many of these cases recount shocking tortures. Drownings, crucifixions, burnings, stabbings, all in the name of exorcism, and most to innocent children or the mentally ill. When The Exorcist came into theaters, just as Anneliese was entering the worst of her final years, "possessed" people joined werewolves and zombies as favorite cinema monsters. It seemed that neither audiences nor filmmakers saw the patients as the victims, but as scary new antagonists to be feared. This perception has almost certainly hampered the efforts of those who want exorcism banned. The exorcism dramatized in the movie was based on a real case. An anonymous young boy, given the pseudonyms Robbie Mannheim or Roland Doe, was exorcised by three priests in 1949. He survived, and went onto to have a successful family and career, but this is largely because his condition and exorcism were far less dramatic than the fictionalized version presented in the book and subsequent movie. One of the priests, Rev. Walter Halloran, gave a 1999 interview to Strange Magazine in which he revealed never having witnessed the bizarre incidents attributed to the boy: speaking Latin in a strange voice, having extraordinary strength, vomiting, markings appearing spontaneously on his skin. He did say the boy spat a lot and he saw the bed move once, but only when he leaned against it (it was on wheels). Nevertheless, the movie character based on this boy is one of cinema history's all-time most infamous monsters. Anneliese had been a pretty young woman with striking black hair. As a child, she often played at her father's sawmill, and by all accounts her childhood was largely normal and happy. Even through the early years of her seizures, she was studying to become an elementary school teacher. Anneliese might be teaching in a Bavarian schoolhouse today, had she not been one of the unlucky few who were unable to make it through a troubled youth. She was a complex and talented person, who had humor and love and flaws and dreams. I've given an example in this episode of exploiting her torture and manslaughter to make a scary sounding podcast. Filmmakers have exploited these victims to make not just The Exorcist, but a slew of other copycat films based on specific individuals, including Anneliese. Every time Linda Blair's head spun around, or she spat green vomit, we laughed and had a riotous old time at the theater. Would the same movies have been made exploiting the victims of other true-life crimes, and would we have laughed at the depictions of those actual victims in their dramatized death throes? For some reason, exorcism seems to have been given a pass, on the mistaken presumption that it is the victim who is the monster. These victims are often critically ill individuals — they may have medical or psychiatric problems that need treatment — they deserve neither to be tortured, killed via negligent manslaughter, nor to have their ordeal glorified as some kind of pop-culture horror story. Exorcism is a brutal, heinous, medieval torture ritual justified only by ignorance. Its roots as a religious rite are irrelevant; a crime is still a crime. In this century, we have the means to actually help sick people. Do not condone the primitive obscenity that is exorcism.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |