|

|

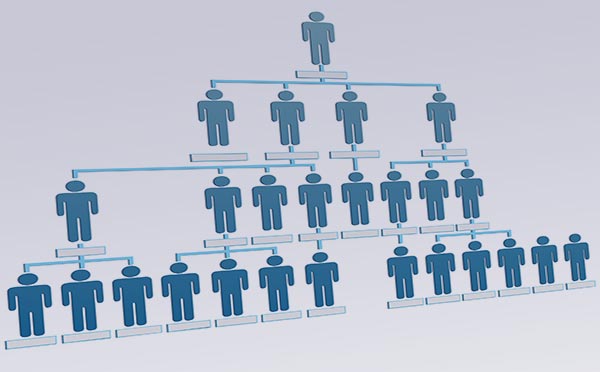

Network MarketingSkeptoid Podcast #176  by Brian Dunning Today we're going to point our skeptical eye at network marketing plans, formerly known as multilevel marketing or MLM (name changed to escape the stigma). They say that when there's a gold rush, the way to make money is to sell shovels. Network marketing companies sell shovels, along with dreams of gold: All you have to do is go out there and dig, dig, dig, and buy more shovels, and get your friends to buy shovels too. Levi Strauss and other suppliers became millionaires, and hundreds of thousands of miners went broke. Network marketing plans are started by a company selling some product — fruit juice, soap, vitamin pills, water filters; anything, it doesn't matter — through a network of independent distributors who are promised exponential commissions by recruiting multiple levels of other distributors beneath them. The company is guaranteed sales because the distributors are required to make minimum purchases, on which commissions trickle upward. There's little need to actually go out and try to sell the product to anyone; money is made by building your network of distributors beneath you, and their distributors beneath them. Soon the commissions trickling up from all those monthly purchases combine into a raging torrent of cash. And if you just buy a few more shovels, you're sure to strike gold. Network marketing plans differ from illegal pyramid schemes only by one subtle point: Commissions can only legally be paid on sales of a physical product. If commissions are offered upon recruitment of new distributors, then it's defined as an illegal pyramid scheme. Pyramids are illegal because they necessarily collapse when nobody else can be recruited. However the illegal plans are pretty rare; most companies are smart enough to stay on the right side of the law. But the problem of community saturation, and inevitable collapse, remains. A tipoff that should clue you into the wisdom of network marketing is that the companies themselves, who manufacture and sell the product, don't even eat their own dog food. They are making money the old fashioned way, by selling an expensive product. It's you whom they recruit to start a network marketing business. When an existing distributor pitches you and gets you to become a distributor yourself, you are required to make your initial purchase of "inventory" of whatever the product is. You either consume that product yourself or sell it to others. Your principal sales tool is the pitch that if your customers become distributors beneath you, they can buy the product at a discounted wholesale price. In most plans, in order to retain your distributor status and qualify for the wholesale discount, regular monthly purchases have to be made. But even this discounted wholesale price is usually far higher than the market value of comparable products available from the supermarket. Participants nearly always find themselves in the unenviable position of having invested a lot of money in their own required inventory purchases, and desperately trying to recruit new distributors in an effort to earn commissions on their inventory purchases, and hopefully recover their own investment. So this raises the question: How often does it work out that way? How many MLM participants ever recover their own investments?

So if network marketing plans don't work, why do people buy into them? Network marketing plans are easily sold by simply laying out some compelling mathematics on a whiteboard. A typical program sets five downline members as the goal for each participant: To be successful, you need only recruit enough people to end up with just five who actively participate. Below those five are their five apiece, totaling 25. This is your network. Each downline of five are qualified by participating at the minimum required level, so this model already excludes everyone who is flakey or only half-hearted, leaving only the five good ones in each downline. Your commissions based on those minimum participation levels — where all five below you dutifully make their minimum monthly inventory purchases — guarantees you an impressive income. The mathematics are black and white, and it's so simple that nothing can go wrong. You'd have to be stupid not to do it. But here is the problem that these whiteboard presentations always manage to omit. Of all the thousands of network marketing plans available now or in the past, if only one of them had ever had even a single line active to only 14 levels deep, that alone would have required the participation of more human beings than exist. That math is black and white, too. Level 14 is populated by 514, or about 6.1 billion people, the entire population of the planet, in addition to level 13 with 1.2 billion, all the way up to you and your original five. You can answer "Oh sure, but a lot of the people don't get all five or they flake somehow," but you forget that the entire premise has already eliminated those who flake or who don't get all five. The unfortunate conclusion is that a fully invested network, upon which the whiteboard presentations are dependent, has never actually happened. A fundamental reason that such networks fail is that they depend upon recruiting people to compete with you. If you own a shoe store, and you pitch every customer on opening their own shoe store instead of being your customer, very soon you're going to have a neighborhood full of shoe stores, with everybody trying to sell and nobody left to buy. It doesn't take an MBA to see that this is pretty much the polar opposite of a sound business strategy. Let's say you tried to make it sound, and said "Forget the multilevel recruiting, I'm going to focus on selling the product." Is anyone doing that successfully? It would not appear so. During yet another lawsuit in the UK, the government found that less than one in ten participants ever sold even a single product to another person. Since the company has its distributors as a captive audience required to make regular purchases, the products are typically grossly overpriced compared to similar products available in supermarkets. This makes their sale a dubious prospect for those few distributors who ever do attempt retail sales to customers. Surveys show that nearly all products purchased by network marketers are consumed by the distributors themselves. This fact is rarely mentioned in the sales pitches. Instead, they typically promote the merchandise (referred to as "lotions & potions" by MLM critics) as wonderous super products that will be in high demand. But, you should always beware of success stories coming from MLM distributors. Most MLM companies pay shills who lie about having had multimillion dollar success with the scheme. These are typically the ones who travel around giving seminars, pitching motivational materials, and putting on recruiting extravaganzas that have been criticized by the Federal Trade Commission for promoting an almost cult-like religious mania as a substitute for sound business practices. I've spoken with enough friends and other people who are into network marketing to know that the default response to this is "Oh, but this plan is different." Sure, every plan has different tweaks and details, but fundamentally they are all the same. The company is going to make tons of money selling an outrageously overpriced product every month to their captive audience buyers: You, and any friends you recruit. Not one of you has any realistic hope of coming out ahead. My advice to everyone involved in network marketing: Simply stop now. Stop convincing yourself that profits are just around the corner if you just buy a few more cases of expensive product. Just stop now, walk away, consider it a lesson well learned, and don't give them another dollar. One final tidbit I'll leave you with. On average, 99.95% of network marketers lose money. However, only 97.14% of Las Vegas gamblers lose money by placing everything on a single number at roulette. So if you're thinking about joining a network marketing plan, and aren't dissuaded by the facts I've presented, consider instead going to Vegas and placing all your money in a single pile on number 13. Sooner or later you're going to have to take my advice and just stop now.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |