|

|

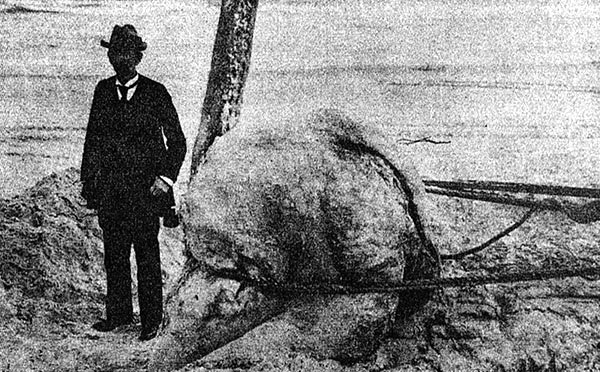

Attack of the Globsters!Skeptoid Podcast #152  by Brian Dunning St. Augustine, Florida, 1896 — It came from the sea, its great bulk suspended in the gentle surf, until it began to drag along the sandy bottom. A final push from a larger wave and it took hold upon the beach. Its mass settled and the water receded. The body of Octopus giganteus, the largest creature ever to swim in the sea, had washed ashore. Tourists and media flocked to see the five ton remains of the fearsome beast. What became known as the St. Augustine Monster had made its mark on history, and established itself as the first in a long line of creatures collectively called globsters: Great globs of unrecognizable tissue washed up on beaches, too large and shapeless to be anything but sea monsters. All too often, the default skeptical position has been to brush these off as misidentified whale parts or some other marine life that has decayed to the point of being unrecognizable. And that explanation is certainly true in many cases, probably in the majority of cases. But to be a responsible skeptic, you can't simply ignore the small number of cases that don't fit that explanation. The fact is that a few of these globsters are not consistent with the usual suspects, like whale blubber or basking shark carcasses, and that's something skeptics should be aware of. Some of these few globsters that genuinely do defy expert explanation do actually appear to be more consistent with the cryptozoologists' preferred interpretation — that of a legendary, gargauntuan, undiscovered cephalopod that they call Octopus giganteus: Too big to be a whale part, too shapeless to be from a giant shark. And it's these few of the strangest globsters that are worth a skeptical examination.

There has been a larger number of specimens washed up that have included recognizable anatomy, such as bones and teeth, that have made positive identifications possible, despite the unrecognizable condition of the carcass. Often all that remains are the strongest structures like the spine and fins, sometimes giving the carcass the look of a long, thin sea serpent. When samples of such carcasses have been preserved and later been able to be tested with modern analysis, they've always turned out to be known animals. Some of the frequent culprits include basking sharks, which leave enormous carcasses of incredibly tough cartilage; and beaked whales, which can be huge but have long reptilian-looking snouts that often baffle observers. A few of the best known cases of such beasts have been the Bermuda Blob of 1988, the Japanese Carcass Catch of 1977, Scotland's famous Stronsay Beast of 1808, and the Newfoundland Blob of 2001. Another important category of globsters are those for which we simply have insufficient data. Many famous globsters have managed to become so without any good evidence: Nobody took a photograph, no samples were preserved, and all we have are verbal descriptions from witnesses. If you do any reading about globsters, one thing you'll learn quickly is that the verbal descriptions vary widely. When the partial carcass of a beaked whale washed up in Santa Cruz, California in 1925, measurements taken by different people placed its length at 20 feet, 35 feet, and 50 feet. Weight is an observation that should be taken with an especially large grain of salt: In all my research I've never once found a case where someone wrangled some enormous scales down onto the beach and actually weighed a globster, yet in virtually every account you'll read claimed weights of 2 tons, 5 tons, even as much as 70 tons in the case of the Suwarrow Island Sea Serpent. When the stories are accompanied by photographs, these weights are often clearly grossly overestimated. Take all the measurements you read with a grain of salt. They are almost always off-the-cuff guesses by random laypeople, usually passed along second or third hand, and obviously often exaggerated. But even in the cases where descriptions are good and photographs are available, it's sometimes impossible to make a definite identification without a sample. There are good photos available of many globsters, including the St. Augustine Monster. A local physician, Dr. Dewitt Webb, was the only scientist to see the creature in person, and though his expertise was in medicine and not in ocean creatures, he felt confident enough to identify it as a giant octopus, believing that some of its shredded appendages were the stumps of huge tentacles. Based on this tentative identification, Webb sent photographs to the nation's leading authority on cephalopods, Professor Addison Emory Verrill. At first Verrill thought it might be Architeuthis, the Giant Squid. In one article he wrote, Verrill changed his mind and concluded that it could be an octopus; but since it was many times larger than any known species, he assigned to it a new name, and the term Octopus giganteus was born. Interesting, that based on an early assumption by Webb, a man with the best of intentions but the wrong background, only the cephalopod explanation was considered. Should he not also have sent samples and photographs to whale experts and shark experts, and allowed alternate theories? Does the lack of a known explanation force us to conclude that there can be no known explanation? There is a clue to the identity of a lot of globsters hidden within the witness descriptions. Often, you'll read that the creature was covered with white fur, or sometimes brown fur. Sometimes stiff, pointed quills are reported. White fur or quills are an immediate tipoff that what you're looking at it is almost certainly deteriorating connective tissue, which is made of collagen. Collagen is the most abundant protein in mammals and most other animals. It's a long, sturdy, triple-helix molecule and is the major component of strong connective tissue like bones, tendons, ligaments, and cartilage. Leather is strong because it's mostly collagen. Those indestructible tendons that get in your way when you carve a turkey are a hassle because they're mostly collagen. Many of the ligaments in your body are strong enough to lift a car because they're mostly collagen. Suffice it to say that if you're looking for durable biological material, look no further than collagen. Collagen is usually the last part of a body to decompose, and marine animals have a lot of it in their skin and in whale blubber. As this collagen-rich soft tissue decomposes, it leaves behind a mat of white fibers, which can have the appearance of dirty, shaggy, white fur. Throw in some tendons and you've got quills too. So keep an eye out for white fur when you read globster accounts; it's a great clue that you're very likely dealing with a big piece of the skin or blubber of a whale or other large animal. So I found the collagen explanation quite satisfying for a number of the so-called "unidentifiable" globsters. But let's go back to what we were saying earlier, about those few cases where that interpretation truly doesn't fit the photographs. I'm speaking most specifically of the 1896 St. Augustine Monster, which was simply too big, thick, and solid of a mass to be a big piece of blubbery whale skin. I would also consider the 1960 Tasmanian Globster, the 1990 Hebrides Blob, and possibly the 1997 Four Mile Globster from Tasmania to fit this category: Well explained as collagen, but of sizes and shapes poorly explained by any known sources of collagen. Indeed, in 2004, amino acid analyses of samples taken from the St. Augustine Monster and five other famous globsters confirmed that they were all whale collagen. Probably most of these globsters were chunks of blubber. But is there something else — something bigger and thicker than blubber — that could give the St. Augustine Monster the shape of the body of a giant octopus? A sperm whale's junk is the lower section of the spermaceti organ in its head. Making up a quarter of a sperm whale's entire mass, the complete spermaceti organ can weigh over ten tons and produces the sperm whale's distinctive head shape. It's encased within a huge, thick, fibrous muscle called the maxillonasalis muscle. Most of the organ consists of a huge sac of spermaceti oil, the stuff most prized by whalers of old. But the bottom third of the organ, weighing up to three tons itself, is the junk. This is a sac with much denser oil, and it was called the junk and discarded because it's filled with extremely tough collagen partitions. Whatever other function the junk might have, sperm whales also use it as a battering ram, having even sunk whaling ships with it, most notably the Essex and the Ann Alexander. This giant mass of tough collagen fibers is one of the hugest and most durable pieces of anatomy in the entire animal kingdom, and yet it's something almost nobody has ever heard of, or certainly would be able to identify if it washed up on a beach. If you found a shapeless three ton mass of collagen on a beach, what would you think it is? Surely nothing recognizable; it's no wonder they went for the Octopus giganteus option. Might the St. Augustine Monster, or even some of the others, have been sperm whale junk? Of course I can only speculate, but Professor Verrill knew a little better. Dr. Webb sent him a sample, and upon examining it, Verrill said that it was definitely not a cephalod, but rather cetacean tissue. He even said "The whole mass represents the upper part of the head of [a sperm whale], detached from the skull and jaw." And yet, cryptozoology websites still uncritically embrace the Octopus giganteus identification. The takeaway should be that there are still perfectly plausible explanations, no matter how alien the globster seems. When you hear people conclude that there is no natural explanation just because they don't know one, you should always be skeptical.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||