|

|

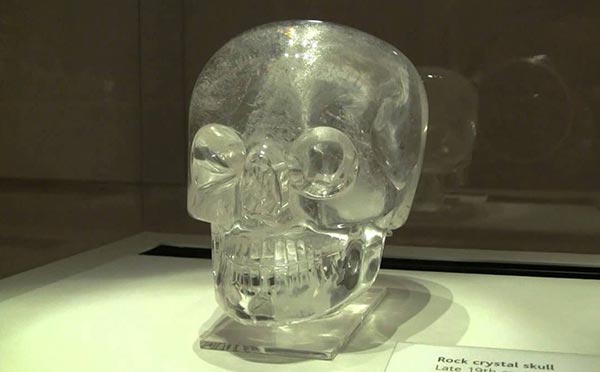

The Crystal Skull: Mystical, or Modern?Despite their reputation for mystical powers, crystal skulls are neither ancient nor mysterious. Skeptoid Podcast #98  by Brian Dunning It was 1926 when Anna Mitchell-Hedges, adoptive daughter of British adventurer and author Frederick Albert Mitchell-Hedges, was something of a real life Lara Croft. She was crawling through an ancient Maya temple in Belize, long ago wrecked by the ages and the ravages of the encroaching jungle. Beneath a crumbled altar, she unearthed perhaps the most curious artifact from the ancient world: A perfectly clear crystal skull, expertly carved, and immaculately preserved, and about two thirds the size of a real skull. For nearly 30 years the Mitchell-Hedges family kept the crystal skull a secret, until F.A. Mitchell-Hedges mentioned it briefly in his book Danger My Ally. In this book he said the skull was 3,600 years old, and was used by Maya priests to strike people dead by the force of their own will. After her father's death, Anna took this so-called "Skull of Doom" on tour throughout the world, and its strange powers became well known. Arthur C. Clarke even used the Mitchell-Hedges skull as the logo for his television series Arthur C. Clarke's Mysterious World. The fourth Indiana Jones movie is about a crystal skull with mystical qualities, and furthers the theme originally proposed by Mitchell-Hedges that crystal skulls are alien in origin, coming from Atlantis or Roswell or some alien world. In fact, practically every reference to a crystal skull over the past 40 years or so has usually been specifically about the Mitchell-Hedges skull. Some believers in mystical energy feel that the crystal skulls have a broad range of powers. They can be used to aid in divination, in healing, and even psychic communication. Others claim that they have refractive properties unlike other crystals. They are said to remain at exactly 70 degrees no matter what temperature they are exposed to. They possess spiritual auras that can be photographed. Some even speculate that when all the crystal skulls are brought together, it will bring about the end of the world. Now, I'm reluctant to burst anyone's bubble, but before going further it's necessary to clear up a few misconceptions. The Mitchell-Hedges skull is not quite 3,600 years old, and Mitchell-Hedges found it a little closer to home than Belize. In fact, he bought it from Sydney Burney, a London art dealer, through a Sotheby's auction on October 15, 1943, as determined in hard black and white by investigator Joe Nickell and others. This explains why neither Mitchell-Hedges nor his daughter ever said anything about it following their alleged 1926 discovery. They had never heard of it, until they bought it 18 years later, and then invented their Maya altar story. So this Sydney Burney character, perhaps he was the one who actually found the skull in a Maya ruin, and traced its history back to the Atlanteans? Well, there is additional hard evidence that Burney owned the skull as far back as 1933, because he wrote a letter about it to the American Museum of Natural History, which they still have. Three years later, the British anthropological journal Man published an article about Burney's skull, and this 1936 article remains the earliest known documentation of any crystal skull. I've since received an 1887 New York Times article in which a paper was presented about a skull — see next paragraph. —BD It seems clear, but has never been never proven, that Burney bought the skull from French collector Eugene Boban. The timing was right; the two men knew each other; and Boban is known to have sold at least two other crystal skulls about the same time Burney acquired his. If Mitchell-Hedges was the real Indiana Jones, Eugene Boban was the real Belloq. He was even French. And, like Belloq, he didn't actually go into the jungle tombs personally to acquire his artifacts. In Boban's case, he simple purchased them in bulk from the manufacturer. This time, the manufacturer was Germany's so-called "capital of the gemstone industry" Idar-Oberstein, a bucolic hamlet where artisans and craftsmen chip away at semi-precious stones in their workshops like so many Gepettos. In the 1870's, craftsmen in Idar-Oberstein made a large purchase of quartz crystals from Brazil, from which to make carvings. Nobody has ever found documented proof, but at about the time the Idar-Oberstein craftsmen were selling their cunningly carved art objects of Brazilian quartz, Eugene Boban left from there with at least three, and possibly as many as thirteen, freshly carved skulls made from Brazilian quartz. Any connection you choose to draw is purely speculative. According to documents found by Jane Walsh, a Smithsonian archivist, Boban sold one of his skulls to Tiffany's in New York City, which in turn sold it to the British Museum in 1897. Boban sold a second skull to a collector who then donated it to the Museum of Man in Paris. An 1887 New York Times article describes the British Museum skull then in the hands of New York collector George H. Sisson, who had bought it from Eugene Boban. After this article, Sisson sold this skull to Tiffany's. —BD For decades, the British Museum and the Museum of Man displayed their crystal skulls with the provenances originally provided by Eugene Boban, which was that the skulls came from pre-Columbian Aztec origin. But then, in separate studies in the 1990's, both the British Museum and the Smithsonian examined a number of crystal skulls, including all of those in museum collections attributed to Eugene Boban. Analysis of the cut and polish marks by electron microscope proved that they were made using 19th century rotary cutting tools, identical to those in use in Idar-Oberstein at that time. The British Museum now lists their skull as "probably European, 19th century," and "not an authentic pre-Columbian artifact." The Paris skull, also from Boban, was subjected to even better tests in 2008, confirming that its polishing was done using modern tools. In addition, particle accelerator tests found traces of water used during the cutting and polishing, occluded within the quartz, that positively dated the carving to between 1867 and 1886. Neither the Mitchell-Hedges nor their skull's current owner, family friend Bill Homann, ever allowed the Mitchell-Hedges skull to be tested with modern equipment; nor have any of the owners of other famous crystal skulls like the one called Max in Texas. The privately owned skulls now confine themselves to touring to mysticism conventions, New Age hotbeds like Sedona, and charging for private viewings and sessions. So far as I've been able to find, no private crystal skull owner has ever allowed controlled tests of their claims of any mystical powers they say their skull has. If they'd like to, this is my personal guarantee to fast-track them to the James Randi Educational Foundation's million dollar prize. There is enough of a gap in the early history of the Mitchell-Hedges skull that we cannot absolutely trace its lineage from the Idar-Oberstein workshops in the 1870's to the hands of Sydney Burney in 1933. Everything known about the skull is consistent with that history, and no evidence has ever been presented that the skull might have any other origin. There is the Mitchell-Hedges' own story of having found the skull in their pulp-fiction Maya tomb adventure, but that story has been conclusively proven to be a fabrication by documentation from Sotheby's and Burney. All of this makes it rather difficult to form an opinion about the mystical powers of crystal skulls. If these powers are attributed to their Maya, Atlantean, or alien origin, then that attribution is conclusively false, but that doesn't mean the mystical power itself doesn't exist. The first thing the claimants would need to do is articulate exactly what the supernatural power is, and then demonstrate it under controlled conditions. Neither of these has ever been done, so a truly critical analysis has nothing to advance it beyond a null hypothesis. And so there we have it: All known crystal skulls are of modern origin, with no unusual properties, and no coherent or testable claims of anything out of the ordinary. Indiana Jones might make great entertainment, but it makes poor archaelogical history.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |