|

|

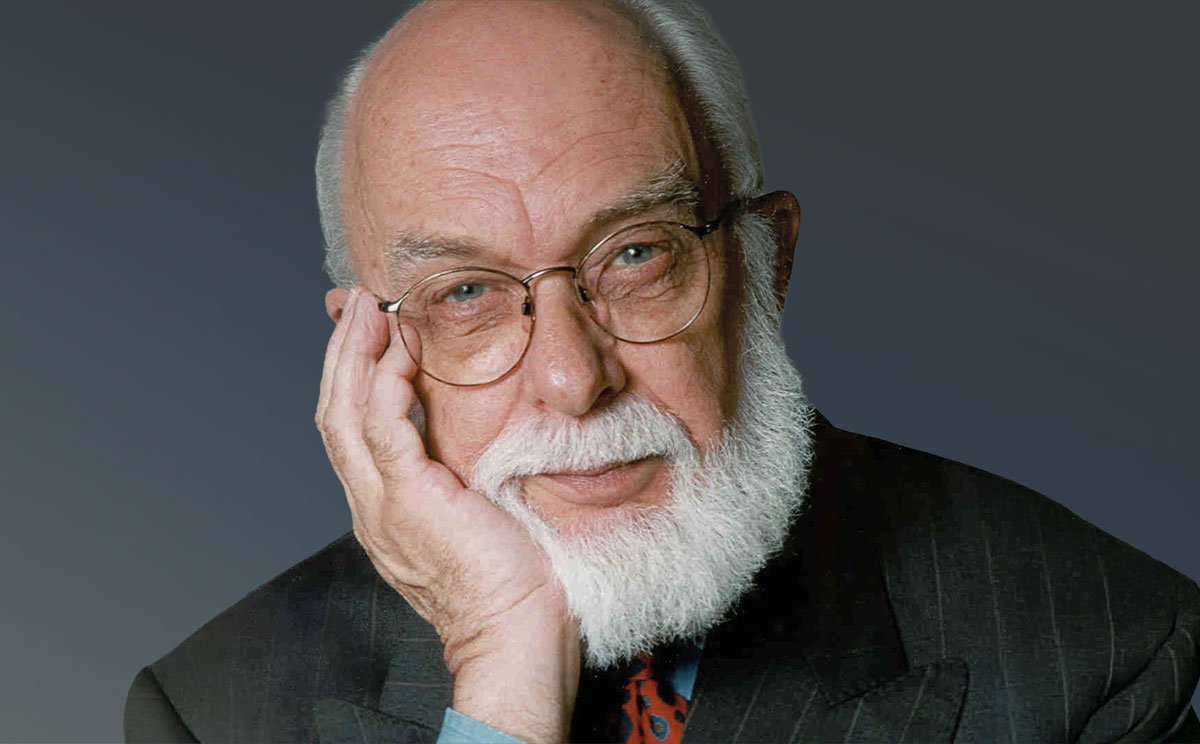

Are $1,000,000 Paranormal Challenges Effective?Skeptoid Podcast #989  by Jeff Wagg I worked for the James Randi Educational Foundation from 2005 until 2010. Those were exciting times, and one of my roles was to administer the $1,000,000 Paranormal Challenge, which promised that sum to anyone who could demonstrate a supernatural or paranormal ability under agreed-upon scientific testing criteria. While this challenge is the most well-known in recent memory, it wasn't the first. The first paranormal challenge was offered by none other than performer Erich Weiss, more commonly known as Houdini. By 1913, Houdini was a world-renowned magician and escape artist. Stricken with grief at his mother's death that year, Houdini turned to spiritualism, hoping for one last conversation with his most ardent supporter. He visited with several well-known mediums, including Margery Crandon, William Hope, and Eusapia Palladino, only to see through the parlour tricks they passed off as a door to the spirit world. This enraged him, and he dedicated his life to exposing those who would use his art form, the art of illusion, to perpetrate fraud on unsuspecting victims. Those who tried to deceive him were soon exposed, publicly. In the early 1920s, Houdini offered a substantial sum of $10,000 to anyone who could demonstrate a supernatural or paranormal ability under controlled conditions. As you might have guessed, none were successful. In the following decades, a young man by the name of Randall James Hamilton Zwinge was growing up in Toronto. He became enthralled with magical arts, and after seeing a performance by the legendary Blackstone, and he decided to become a professional magician known as James "The Amazing" Randi. In practice, however, he followed in the footsteps of not Blackstone, but Houdini, becoming a magician and escape artist who performed some of the same feats that stunned Houdini's audiences. And, like Houdini, he became enraged by those who would bilk people out of their money and dignity by performing things he recognized as simple illusions. Randi spoke out publicly about these charlatans, and it was when he found himself on a radio panel in 1964 that his own challenge burst forth — although he wasn't the one to issue it, it was issued to him. Randi claimed to not be able to remember exactly who it was who said it, but a parapsychologist on the panel told him "Put your money where your mouth is." And so he did. And in increasing amounts. Over the years, the challenge amount grew from $1,000 to $10,000 to $100,000, which was funded by 2,000 supporters who agreed to each pay $50 should the challenge be won. Finally, in 1996, a wealthy man who'd just received a windfall during the dot com boom offered him $1,000,000 cash, which Randi accepted, as he would say, rather quickly. This money was set aside and the James Randi Educational Foundation was created to administer the challenge and to support Randi's efforts to educate the public about an evidence-based worldview. For the challenge, strict terms were drawn up, which included an important clause that both parties, the JREF and the claimant, had to agree completely on the protocol. There was nothing secret, and there was no judging allowed — the results would be plainly obvious to everyone. Either a coin is heads or tails, or the correct envelope is identified. Nothing resembling "that kinda looks like a house, and that's what I was thinking" would be allowed. Having been intimately involved with the details of several challenges, I will state that the challenge was absolutely honest, the money was real, and that if someone really had these abilities, they would have won easily. Randi once said "he always had an out." That out, he would later explain, was that he was right. But what is the purpose of these challenges such that we can deem them effective or not? For Randi, it was, as he would say, "a street fight." Randi wanted the same as Houdini: to expose those who would try to defraud people with sometimes very simple tricks. This included psychics, mediums, astrologers, medical quacks such as homeopaths and energy healers, Kirlian photographers, cloud busters, dowsers, and so on. Folks who claim these abilities fall into three categories: those trying to defraud, those that truly believe they have powers, and a subgroup with mental health challenges. Those three categories require more analysis to determine the challenge's effectiveness. Randi's main target was famous fraudsters. His hope of TV "psychics" such as James Van Pragh, John Edward, and Sylvia Browne taking the challenge and being exposed, did not materialize. He would publicly offer the challenge to them whenever he could, but they would either ignore him, or fail to follow through. Sylvia Browne did agree to take the challenge on the Larry King Show, but then claimed she couldn't find a way to get in touch with him, despite a website with his name and a common tool of the time: the phone book. Some psychic. But Randi had formed an educational foundation, not simply an organization to administer the challenge. As such, one of the uses of the challenge was to serve as an educational tool and rhetorical device to demonstrate that the people having these powers should be doubted. The challenge was open to everyone. A claimant simply had to state three things: what they could do, under what conditions they could do it, and to what degree of accuracy. Hundreds of applications poured in. So many came in that it became a burden on the meager staff, especially when most of the applicants couldn't provide those three simple things. Rules were set in place such that only serious claimants could start the lengthy process of establishing a testing protocol. At first, they merely had to get the application notarized. When that didn't reduce incomplete claims enough, the JREF hired staff just to deal with the applications, and new rules were put in place. Since the challenge was designed to expose people with some public presence, a claimant now had to have a mention in a newspaper, magazine, or on a TV show, and the reporter or other responsible party would have to sign an affidavit saying that they actually witnessed the person perform the feat. In later years, as the JREF changed focus somewhat, this was changed to a scientist rather than a media entity. Despite the lack of complete fulfillment of that goal, the challenge did have a use against famous charlatans: if they really had the powers they claimed, why not take the $1,000,000 away from Randi? The money was real, the challenges were agreed to by both parties, and that $1,000,000 would have easily been theirs if they had only bothered to collect it. Some said "they didn't need the money," but would any reasonable person turn down $1,000,000, even if they were to simply turn it over to a charity of their choosing? These arguments, while not evidence against a claim, do cast doubt and that can be effective on its own. When claims were made and challenges were agreed upon, and this happened dozens of times, they were all brought, to the best of our knowledge, by the second category of claimant: sincere people who believed they had the abilities they claimed. Not one of them came close to winning the challenge, despite it being designed to their exact standards. The results were always what chance predicted. Did they learn anything? Some did, but very few. The most common reaction was confusion, a level of acceptance, and then an excuse perhaps a week later. "It was sunspots" or "Randi's psychic ability dampened my own." But while this may render the challenge ineffective against these particular claimants, the entire exercise was witnessed by many, and the events were well documented. The JREF then had a large set of examples where people could be shown that they too could be fooled. As an educational tool, I believe the challenges are effective. They provide data that can be examined, and examples of people who sincerely believed they had a special ability — one they may have demonstrated under informal conditions — but when tested under controlled scientific observation, the effect disappeared, revealing it as self-deception. And that takes us to the third category: the mentally unstable. I am in no way qualified to judge someone's suspected disorder. That aside, it was plainly obvious that many of the folks who submitted claims to the JREF were suffering greatly. Some were merely grief-stricken as Doyle had been, others seemed to be experiencing some form of narcissistic delusion, where they believed they had special favor with some deity or other, or actually were that deity. One of them actually sued the JREF because they claimed that "Randi had stolen his powers from God," and yes, they were God. Hypergraphia, a condition in which people can't stop writing, was very common, with claims containing dozens of pages of hastily handwritten details, which we did not ask for, which would often continue on the outside of the envelope, as though the person simply couldn't stop. This is a known symptom of schizophrenia, but again, diagnoses should be left to professionals. I truly wish the JREF had the resources to have a psychologist on staff or perhaps a partnership with a mental health institution who could have reached out to these folks, but nothing like that was possible with our limited budget. In this regard, the challenge, in my opinion, was capable of doing harm. The JREF staff were in a dilemma where, if they took these folks seriously, they'd be feeding into their struggle. And if they didn't take them seriously, they could be accused of ignoring "the real psychics," which was a frequent criticism. In the end, such folks were filtered out by the more restrictive rules, but I still think of the desperation in those letters and phone calls and it leaves me uneasy. So I think paranormal challenges can be effective in a number of ways, but they're not going to take down the big names, and they have to be managed carefully and with compassion. The endeavor of exposing fraud rarely has the cooperation of the fraudster, but both Randi and Houdini were able to expose the cons in other ways. The good news is, there are still a number of Paranormal Challenges active around the world. First, the JREF challenge still exists, but it's by invitation only. There's also the Center for Inquiry Investigations Group Paranormal Challenge of $500,000. The Australian Skeptics have a $100,000 challenge, South African Skeptics have a prize of R100,000, and the Indian Rationalist Association, while it does not have a prize, does offer public challenges, some of which get world-wide attention. In Germany the GWUP (no, I'm not going to try to pronounce that in German) offers €10,000, and in the UK, Merseyside Skeptics Society has been conducting public demonstrations for many years. The Czech Skeptics Club and Norwegian Skeptics have also offered prizes and collaborations with other organizations. If you happen to be the one person who actually has a paranormal, supernatural, or occult ability, I invite you to contact one of these organizations and get tested. At worst, you'll learn something and help educate others. At best, you'll win some money. But not only that, you'll be changing the scientific view of the world, forever. The truth is that we at the JREF often talked about what would happen if someone won the challenge, as unlikely as that might be. Everyone hoped it would be awarded. If we could demonstrate a phenomenon that science could learn from, that would be a major contribution to the world, and something that was easily worth $1,000,000. By Jeff Wagg

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |