|

|

Hunting the Graveyard of the ElephantsDoes a mythical place where the elephants go to die actually exist? Skeptoid Podcast #949  by Brian Dunning People have long been fascinated by the idea of a graveyard of the elephants, a hidden place in the jungle where they instinctively all go to die. Such a graveyard would be a veritable golconda for the ivory hunters, who could freely enrich themselves upon countless thousands of elephant tusks; and perhaps the allure of this idea is why the concept can be found in pulp magazines during the era of European ivory imports. Today we're going to dig into the history of the idea of such a graveyard — if it isn't real, then where did the story come from, and why? It's easy enough to start out with the great big spoiler, which is that there is not now, nor ever has been, such a place in reality. Elephant experts have been studying these gentle giants for decades and their lives, travel patterns, and even their end of life behaviors are well understood. Combined with the fact that the world has now been thoroughly both explored and photographed, we can say with a certainty that the idea of an elephants' graveyard is a fictional one — but that's hardly the interesting part of our story today. Rather, we find that in the history of the idea. The place many people of the current generation may have first encountered a graveyard of the elephants was Disney's 1994 film The Lion King, in which the graveyard is a forbidden place of wonder that the young lion cubs yearn to explore. The story was original, developed within Disney by a number of different writers, and not based on any specific book or other work. Thus its inclusion of an elephants' graveyard was drawn from pop culture in a general sense. Prior to The Lion King, perhaps the most exposure such a mythical graveyard had was in Hollywood's early black and white films. In 1931, the movie Trader Horn told the fictionalized adventures of Alfred Horn, who had been an actual ivory trader in central Africa in the late 1800s. Trader Horn was followed the next year by Tarzan the Ape Man (1932) starring Johnny Weissmuller as the title character. The fabled graveyard took a central role in this film, as explorer James Parker, along with his daughter Jane (played by Maureen O'Sullivan), come to Africa specifically in search of the graveyard for its ivory riches. This theme was expanded by the next film in the series, 1934's Tarzan and His Mate, where Tarzan and Jane must deal with a band of ivory hunters who come to plunder the graveyard. (Fun fact: in the Tarzan movies, Indian elephants were used instead of African, because they were more easily available to the filmmakers and were already trained for movie use. But in a surprising nod to accuracy, the producers disguised them as African elephants with prosthetic bigger ears and longer tusks — something few audiences of the era would have known about.) Another example was the 1956 film Dark Venture, later re-released as Curse of the Elephant's Graveyard, which tells the story of a man who goes to Africa in search of the graveyard — by this time a solid fixture in movies. There he encounters John Carradine playing a sort of guardian of the graveyard. So if the idea of a graveyard of the elephants has had a firm workout in Hollywood, that tells us that it almost certainly existed in the literature upon which movies are so often based. Probably 19th century literature would be a good bet; that's the time period in which so much ivory was being brought from Africa by European hunters and traders. The first place I went expecting to find a grand description of the elephants' graveyard was Joseph Conrad's famous novel Heart of Darkness, the story of a man's quest to learn the secrets of Kurtz, an ivory procurement agent in the Congo, who produced more ivory than all the other agents combined (and, obviously, the book upon which the movie Apocalypse Now is loosely based). In the book, ivory takes on an almost religious stature; and yet, to my surprise, there is no mention at all of anything like an elephants' graveyard — a place where Kurtz's men could have picked up ivory as easily as apples fallen from a tree. In fact the word elephant itself appears only once in the entire book! We can find the graveyard mentioned here and there in early 20th century pulp, magazines, and newspapers. In a 1927 issue of Blackwood's Magazine I find an article about the passion elephant hunters have for their craft:

In 1909, The Independent sent a correspondent through British East Africa to report on his adventures:

And in 1922, the Acting Director of the New York Zoological Park submitted an article to The Guide to Nature in which he speculated on the mystery of where elephants go to die as an actual science question and not just a literary device:

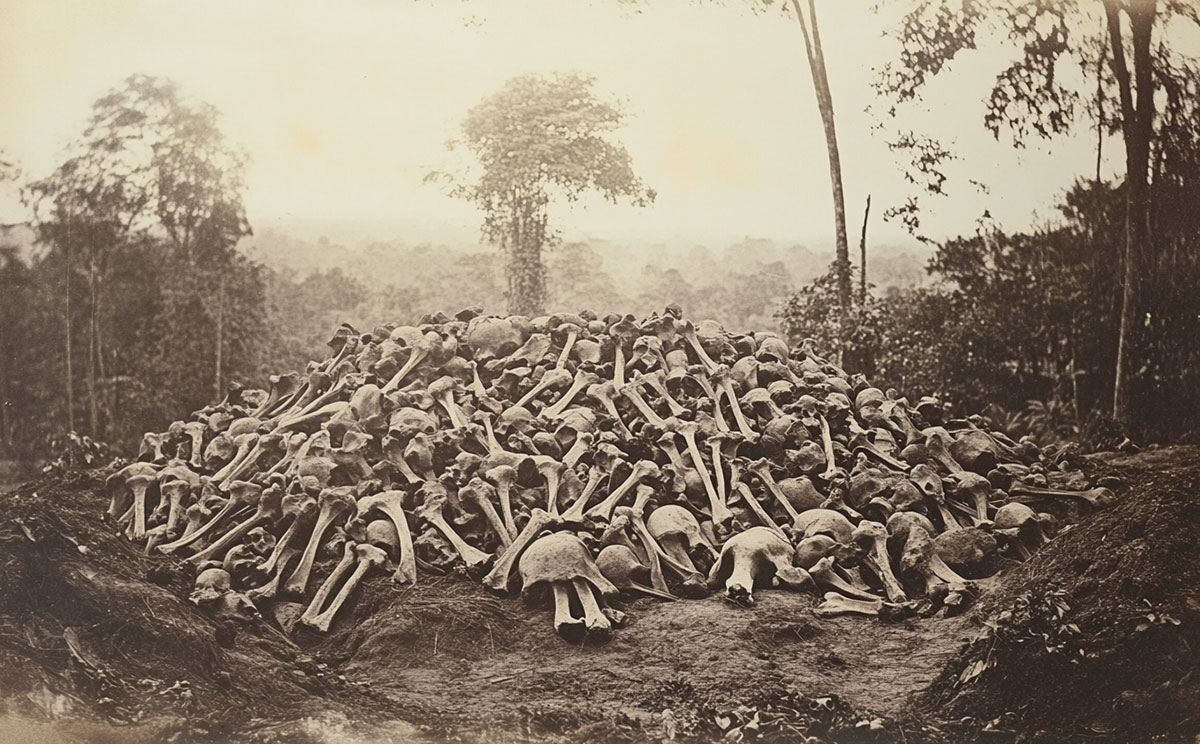

His mention of India suggested that it might be wise to check the Indian literature and not just limit our search to literature concerning Africa. I felt the complete works of Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936) would surely mention it if the concept of an elephants' graveyard existed in Indian fiction. But no; the closest thing found in all his many books is in The Jungle Book (1894), and it's an elephants' ballroom where they would go to dance in a clearing in the jungle. But even this was more of an inside joke among the elephant drivers than it was intended as an actual place. It would appear that the literature of India is not the source of our tales of the graveyard. Turns out we need to go much farther back to find what I think may be the first significant print reference to a graveyard of the elephants, and it's found in later editions of The Book of the One Thousand and One Nights, the famous collection of Middle Eastern folk tales, which included the tales of Sinbad the Sailor. The Calcutta edition, as translated by the polymath Sir Richard Francis Burton, is found in his publication The Supplemental Nights to the Thousand Nights and a Night and features an alternate version of Sinbad's seventh voyage. In this variation, Sinbad is captured and enslaved and forced to hunt elephants with bow and arrow in order to obtain their valuable ivory tusks for his master. Sinbad proves so good at killing the elephants that one day a large group of them ambush the tree he uses as a hiding place. The largest elephant rips the tree down, grabs Sinbad with his trunk and sets him on his back, then carries him off. The elephants finally dump him unconscious, and when he wakes he finds they've taken him to their graveyard where all the elephants come to die, and from where he could now collect all the ivory tusks he wanted without any need to harm any more beasts. Sinbad brings back so much ivory that his master is sufficiently pleased as to set him free, and Sinbad returns to Baghdad a wealthy man. To whatever degree the idea of a graveyard of the elephants may have existed prior to that, it appears that the Thousand and One Nights is the first time it appeared in print. The story itself, like the other tales in the series, are of unknown origin and no date for the story can be established. So the concept went from that, to the early pulp tales of Great White Hunters in Africa, to Tarzan in Hollywood, and finally to The Lion King. And in a connection so remarkable that we would be remiss not to mention it, the Disney animated feature that came out right before The Lion King was Aladdin (1992) — perhaps the most famous tale from the Thousand and One Nights. Finally, there's one more thing that this topic virtually requires us to mention, and it's that today, actual elephant graveyards are all too real — as often as not the result of poachers poisoning waterholes. The tool of choice is cyanide, which is widely and easily available since it's used in mining, and poachers can easily purchase many kilograms of it. Sometimes they leave extra behind, tipping off rangers as to what was used. Obviously it's an indiscriminate way to kill; elephants are never the only victims. Lions, giraffes, hyenas, and any other species that depend on that water hole are also killed, even the vultures feeding off their carcasses. In 2013 alone, 300 elephants, plus many other animals, were killed from cyanide-laced salt pans in Hwange National Park in Zimbabwe. As a herd of elephants would all die in great pain, they would gather together; and rangers would find dozens of elephant carcasses at a time, their heads hastily chainsawed apart to free the ivory tusks. The remains of each herd found would be a real elephant graveyard — one not of mythos, but of horror. This mass poaching with poison presents an enormously complex problem in conservation; not only does it obviously kill the elephants that Zimbabwean conservationists try to protect, it also kills the ones that were slated to be culled because they were old, injured, or aggressive. Had these not also been killed by the poachers, the National Parks and Wildlife Management Authority would have sold hunting permits on these specific elephants, netting them well over six figures apiece, an essential part of their program's funding. It always seems ghoulish to bring up the financial benefits to conservation efforts that legal hunting provides, but the poaching destroys all parts of the elephant conservation ecosystem: the good, the bad, and the ugly. And so we close our historical exploration with a case of fiction unfortunately informing reality in the worst possible way. It inspires us to hope the elephants' graveyard will return to — and permanently remain in — the realm of fiction.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |