|

|

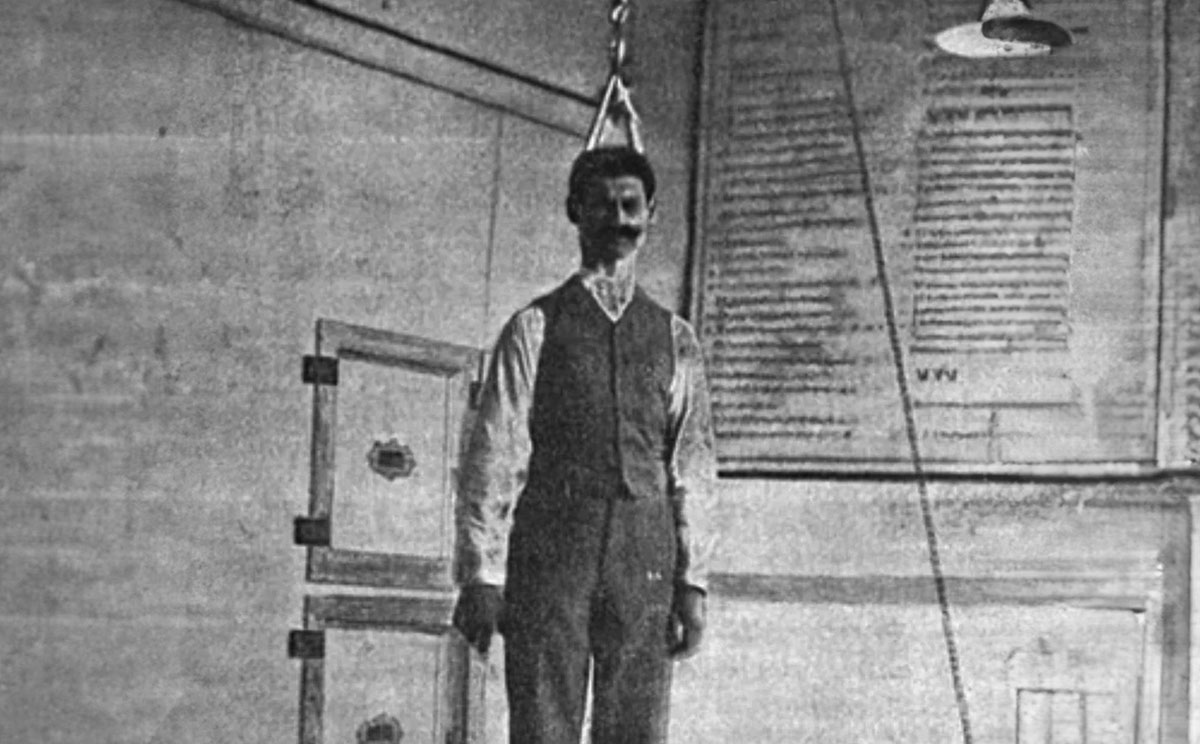

I Can't Believe They Did That: Human Guinea Pigs #3Part 3 in our roundup of scientists who took the ultimate plunge and experimented on themselves. Skeptoid Podcast #927  by Brian Dunning Once again we are going to open our history books and turn to the chapter on scientists who gave it their all by experimenting on themselves, sparing innocent test subjects, and in most cases, willing to subject none but themselves to the worst diseases and torments out there. March 14 is Celebrate Scientists Day, and so today's episode is a chance for us to do just that. It's also Pi Day, 3.14 (for people who write dates the American way), and it's also Albert Einstein's birthday. But today is our third installment of Skeptoid episodes about scientists who really took one for the team (see our two previous episodes on Human Guinea Pigs, episodes #305 and #593). We're going to get started with one from fairly recent history, with a case that is all too relatable for many of us. Stewart Adams (1923-2019)We're going to ease into it today and get started with a case of self-experimentation that is perhaps not the noblest and most courageous, but still an important one. Stewart Adams co-invented ibuprofen, the active ingredient in such pain relievers as Advil and Motrin. In 1971, he was at a conference where he was to present a session about his work. But, as one might do at a conference, he got wildly drunk the night before, and woke up with a hangover that included a splitting headache. What to do? His creation had been found effective for pain relief in clinical trials, and he happened to have a bottle of it with him. What the heck, he figured, and downed a 600-milligram dose. His relief showed that ibuprofen could now take the crown as a miracle hangover cure. Today, conference attendees worldwide owe Stewart Adams their undying thanks for facilitating the nightly post-session partying. Frederick Banting (1891-1941)Canadian doctor Sir Frederick Banting was one of those born overachievers. He discovered insulin, for one thing. He became the youngest recipient to date of the Nobel Prize in Medicine. He was knighted by King George V in 1934. He had seven honorary degrees. And on the side, like, just for grins, he became one of Canada's most important and best known amateur artists, painting and sketching Canadian landscapes. He also served as a doctor in both World Wars. It was during his medical research in WWII that he turned to mustard gas, a chemical warfare agent that causes severe burns to the skin and respiratory tract, in hopes of finding a treatment. Unwilling to subject volunteers to such torture, he administered mustard gas to himself, causing severe burns which he treated himself. The specifics of this do not seem to have ever been recorded in print, but how well he may have recovered doesn't matter much, as he died following a wartime plane crash shortly thereafter. Joseph Barcroft (1872-1947)This Victorian physiologist had an interest in blood oxygenation, and developed quite the reputation for experimenting on himself by pushing his own limits to the max while sealed inside a glass chamber — always dressed in his tweed suit and tie, as any good gentleman scientist adventurer would. Barcroft wanted to test the theory advanced by J.S. Haldane that at high altitudes in low oxygen conditions, the lungs were able to somehow directly secrete supplemental oxygen into the blood. To do this, he spent six days in the chamber with gradually reducing oxygen levels, often riding an exercise bicycle, to simulate a strenuous climb to 5500 meters, often sampling his own blood oxygen levels surgically: exposing an artery in his arm, tying it off, then making an incision directly into it. During World War I, Barcroft ran a similar experiment in a glass chamber with 500 ppm of hydrogen cyanide poison gas, because why not. He and a dog both went inside and sealed themselves in. In just over a minute, the dog fell down unconscious. Barcroft scrambled to get out, bringing the dog's body with him. Barcroft went on a respirator. The dog, now dead, was set aside in the lab while efforts to revive Barcroft were successful; his symptoms lasted only about five minutes. When they came back into the lab the next morning, the dog was walking around perfectly healthy as if nothing had happened. Georg Charles de Hevesy (1885-1966)This Hungarian radiochemist, known as the Father of Nuclear Medicine, had kind of a ridiculously long resume of accomplishments, like winning a Nobel Prize in Chemistry and discovering the element hafnium, but one of the things he's best known for is the development of radioactive tracers: put a radioactive compound into the body, and track the way it spreads to find out where things end up and whether they get excreted. Upon whom did he first try this? Himself, of course. Luckily, Hevesy knew enough about what he was doing that this was not especially dangerous. He took radioactive lead and dissolved it into a solution that he was able to drink. And then, over a period of weeks, he used a Geiger counter to track its dispersal within his body. Today, refined versions of this basic method are used commonly in medicine. He once used this technique to prove to everyone in the house where he boarded that the landlady was collecting uneaten meat from people's plates and recycling it in later meals. On one Sunday, when she served genuinely fresh meat, he spiked his with radioactive lead and left part of it uneaten on his plate. A few days later he brought an electroscope to the table to prove his discovery to all! He did not formally publish this particular experiment. Tim Friede (1968-)Friede is unique on this list in that he was never a trained scientist, just a lover of snakes, especially of the venomous variety. And his snakes loved him back too; so much so that one day his pet Egyptian cobra bit him, injecting him with lethal venom. But he'd been bitten before and had developed a certain amount of resistance to it. That was all well and good, but not even his fortified system was prepared for another bite just an hour later from his monocled cobra. That was too much, and Friede next woke up in the hospital after four days in a coma. And that was all he needed to discover his life's calling. Now the director of herpetology at a vaccination research company, Friede has since allowed himself to be bitten by snakes hundreds of times — nearly all of which have been on purpose, and many of which would kill someone whose system is not prepared for the challenge as his is. Many people around the world live where there are venomous snakes and where lifesaving care isn't exactly around the next corner, and Friede hopes that his work will lead to antivenom treatments that will save countless lives. Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov (1845-1916)Mechnikov was an early giant in the science of immunology. He has been called the Father of Innate Immunity, also the Father of Gerentology; honored with his birthday May 15 being Mechnikov Day, and he shared the 1908 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. He too experimented on himself — though, unlike the others, it was a deliberate suicide; he just hoped that it would benefit others. For him, it was time to check out, and he wanted to do it the right way. It was actually his second suicide attempt; his first, an opium overdose following the death of his first wife, was not successful. For this second attempt, he injected himself with relapsing fever bacteria, and carefully documented his body's responses as he died. But unaccountably, he survived the attempt, only to die later of heart failure, after doing some of his most important work. Nicolae Minovici (1868-1941)This Romanian professor of forensic science first made a splash with a study that found — contrary to popular wisdom — that there was no relationship between a propensity for tattoos and a criminal personality. But it was his self-experimentation with hanging that really swung him into the spotlight. He wanted to know what it was like to die by hanging, and so he hanged himself — quite a few times — until he had a pretty good idea. He tried it with both constricting knots, and unconstricting knots; he tried it by being lifted by his assistants, and by his own hand; and he tried being lifted only partially, all the way up to about two meters off the floor. He described one such experiment:

The longest he ever lasted was 25 seconds. Wisely, he never attempted the version where you drop through a trap door to snap your neck. Justin Schmidt (1947-2023)Justin Schmidt was an entomologist who was best known as the creator of the Schmidt Sting Pain Index, which rates the pain from the stings of various insects on a five-point scale. 0 means it doesn't hurt at all; 4 means the sting feels like — in his own words — "a running hair dryer has just been dropped into your bubble bath." A bee sting is right in the middle, at 2. Schmidt, however, never sought out to be stung — he was strictly an involuntary self-experimenter, despite often being written up as if he set out to do this on purpose, and got himself stung on purpose. As an entomologist catching and handling countless insects, occasionally accidents do happen. He figured he was stung by some 150 different species in his lifetime. Luckily for him never seems to have been allergic. Only three insects occupy the glorified top slot at 4: the warrior wasp, the bullet ant, and the tarantula hawk. But perhaps an equally important question is how long you must endure that agony: with the tarantula hawk, the pain subsides after just a few minutes; but with the bullet ant, it can last for hours. Nicolas Senn (1844-1908)Later the president of the American Medical Association, Dr. Senn made a name for himself by developing a clever test for perforated bowels, often caused by bullets in wartime. This test, which he performed on himself and upon others, was to inflate the bowels with pressurized hydrogen, which could be introduced via a hose inserted into the lower end. If there was indeed a perforation, the hydrogen would bubble out — and that it was indeed hydrogen could be verified by igniting it. Although Senn did not go quite that far on himself, he did describe the inflation experience thusly:

Anatoliy Albertovich Shatkin (1928-1994)This one seems to be the very worst to me, so props to Shatkin for having the guts to do this. Shatkin was a Soviet virologist who specialized in infections of the eye. One of the conditions he worked on was trachoma, a bacterial infection that is the world's leading preventable cause of blindness. It's spread by contact and is caused by the chlamydia bacterium, and is often transmitted by flies. In the early stages it can be treated with antibiotics, but can become very serious, ultimately causing irreversible blindness, if left long enough. Shatkin was determined to find a treatment, as antibiotics were not yet in widespread use in the Soviet Union for trachoma. Not even the mechanism by which it spread was known, so when Shatkin decided to give himself trachoma upon which to experiment, he didn't know that he could have simply rubbed his eye. So he went all-in, filled a syringe with infected fluid, and straight-up injected his eye with it. In order to make sure his case was good and severe, he left it alone for nearly a month before attempting any treatments. How did he fare? Well, records seem to be pretty scarce, so we're going to leave this as an unknown. And so we close this installment of Human Guinea Pigs, and we lift our glasses on Celebrate Scientists Day to those who work the very hardest on our behalf, and go above and beyond the call of duty by experimenting on themselves. Thank you, and cheers!

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |