|

|

What the Oil Companies Really Knew, Part 1Is it true that the oil companies knew how much harm they were doing as far back as the 1970s? Skeptoid Podcast #876  by Brian Dunning By now, most people have heard of the apparent scandal of internal documents having been discovered at major oil companies, mainly Exxon, showing that they knew all about how their product was resulting in global warming with the potential for catastrophic economic and environmental harm. You can search the web for "what the oil companies knew" and you'll get dozens of articles, mainly saying the same things, mainly quoting the same snippets from the same internal memos. These articles paint a grim picture; a picture in which the oil company executives were unambiguously acting in a way that they knew would cause great harm, and even went so far as to launch gargantuan public disinformation campaigns to cover up what they were doing. Massive lawsuits have been filed on this basis, and continue to be filed. But there is more here than is being presented in these articles, which tend to paint an oversimplified, mustache-twisting caricature of the executives. Make no mistake, there is still plenty of blame to go around; but the way it's usually presented is, in my view (having read the documents), not entirely honest. One cannot claim the high moral ground when one's own claim is itself cherrypicked and misrepresentative. Today I'm going to lay out some of this to show what I mean. Distrust of science — and to a larger degree, ignorance of science — have always existed at many levels throughout the general public. All it takes is a powerful marketing campaign to turn a fringe distrust into a mainstream distrust. As a recent example: Anti-vaccine sentiment, or to use the softer press-friendly term "vaccine hesitancy", used to exist at sort of a fringe background level along with other obviously anti-scientific beliefs. But then the COVID-19 pandemic came along, and the anti-vaccine movement was given rocket fuel. In that case, vaccine disinformation became a political party platform; so half the population was hammered with anti-vaccine messaging around the clock. Powerful cultural messaging caused a fringe belief to explode into the mainstream. This is very similar to what happened with global warming. In the 1970s and 1980s, people had scarcely heard of it. Then we began to get the bad news from the climate science community, and renewable energy burst into the limelight. The fossil fuel industry reacted, and funneled countless millions into think tanks — the Heartland Institute, the Heritage Foundation, the Cato Institute, the American Enterprise Institute, the Competitive Enterprise Institute, and more. They've done their best to carpet-bomb the media with white papers and press releases spreading climate disinformation: falsehoods like not all scientists agree; some warming is a good thing; most of the CO2 is natural from volcanoes and such; attempts to mitigate warming would devastate world economies. And so the public got bad information — that powerful cultural messaging again — and climate denial moved from the fringe to the mainstream. Evidence that this messaging was known to be false is the big question. The majority of articles claim that this is unequivocal. A reading of the industry memos does not concur with such a decisive verdict. There's no scientific doubt that the messaging from these thinks tanks was (and continues to be) false; the issue is whether the people who hired them knew it to be so. Did the oil company executives knowingly set out to profit from selling a harmful product, under the protection of false marketing messages portraying global warming as fake? Given that the fossil fuel companies knew global warming meant their product had a limited lifespan, we're tempted to ask "Gee, wouldn't it have made more sense for them to get out in front of it? If they knew the problem was coming, and they knew the solution would lie in renewables, why didn't they leverage their position to pivot to becoming the world leaders in renewables? Why didn't Shell and Chevron put electric vehicle chargers at every gas station, and corner that market too?" I believe there are two answers to this. The first is that it would have been a terrible business move, because the product they were selling, gasoline, truly is one of the greatest products in history. Gasoline is incredibly energy dense, and therefore wildly efficient. It's inexpensive. It's safe to produce and transport. It just has the one little detail: burning it adds carbon dioxide into Earth's carbon cycle, carbon that had previously been sequestered, thus warming the Earth. By the time this little flaw became widely known outside the science community, the entire world already had an efficient and robust gasoline infrastructure. Fossil fuels made the industrial revolution possible, and we owe them the lifestyle we enjoy today…there's just that one little detail. They are cocaine. Use them long enough, and they'll kill you. Our dependence on fossil fuels today is Al Pacino in Scarface, face-down in a giant heap of nose candy. From a sales perspective, their product's market position, today, is worth keeping in place. The second answer to this goes back to the question of what they actually knew. What were the executives actually being advised? That's what we're going to cover now. The science of humans burning fossil fuels directly causing global warming actually predated the fossil fuel companies themselves. It was as far back as the mid-1800s that scientists first began experimenting with gases and learning how they absorbed infrared radiation. Dozens of scientists made important contributions putting the pieces together. It was 1896 when we finally knew enough to understand exactly how much extra heat carbon dioxide would blanket in, and the first truly seminal publications were made. Plant a mental flag right there, and just keep the fact in mind: Prior to the turn of the 20th century, the science community understood that burning fossil fuels would warm the Earth. How much warmer, and over how long, was still beyond our ability to compute with much accuracy. And of course, in 1896, we didn't yet have any concept of just how much fossil fuels would be burned over the course of the 20th century. The 20th century would feature two world wars, it saw the rise of the aircraft industry, the automobile industry, and electric power in every home. Nevertheless, in 1896 the basics were still well understood. An 1899 book by Thomas Chrowder Chamberlin, founder of the Journal of Geology, nailed it; you could pick it up today and not know that it wasn't written today rather than 125 years ago. He discussed in detail the mechanisms for how increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere would trigger changes in global climate. It was two years later, in 1901, that the eminent Swedish meteorologist Nils Ekholm coined the term "greenhouse effect". Check out this newspaper snippet from 1912, under the headline "Coal Consumption Affecting Climate":

In 1959, there was a petroleum conference called the Energy and Man Symposium. Representatives from all the oil companies were there. There was even a famous speaker, the "Father of the Hydrogen Bomb" Dr. Edward Teller. Teller told the oil executives:

Lest you counter that Teller wasn't part of the oil industry and just because he said so doesn't mean the oil executives knew it, let's hear from one of their own, arguably their highest ranking representative. The American Petroleum Institute is the trade association for the United States fossil fuel industry. In 1965, the president of the API was an oil industry lobbyist (and former Congressman) named Frank Ikard. At their Annual Meeting, he presented a report from the President's Science Advisory Committee. He said:

That's where the popular quotations of Ikard's presentation end, with what appears to be a stark warning to his industry colleagues. But it turns out this is a cherrypicked snippet, for "stark warning" does not remotely characterize the overall tone of his talk. In fact, Ikard continued, in his very next words:

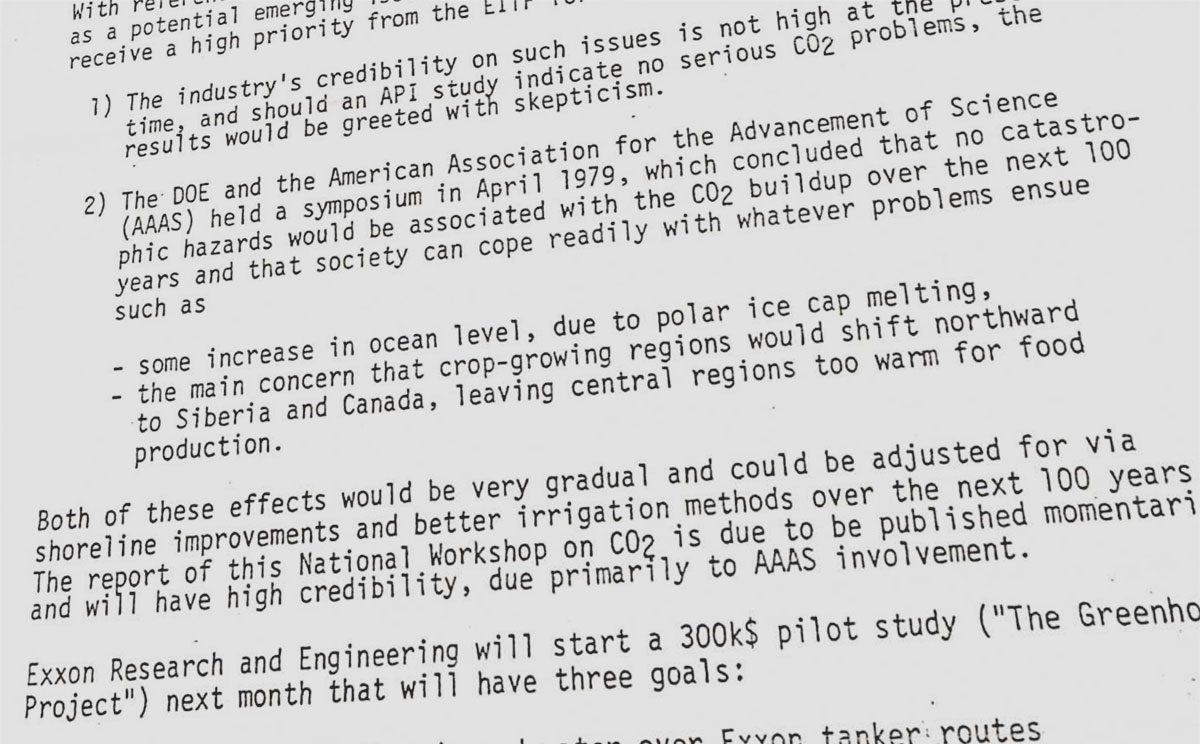

Not only did Ikard completely miss the point of the report he was quoting, thinking it to be about the damage from air pollution to people; he was downplaying it, claiming it's not as bad as cigarettes. Ikard's talk was not, as is popularly reported, evidence that industry knew of the harm their CO2 emissions were doing to the climate. It was evidence that industry — or at least, Ikard himself — was entirely unconscious of the nature of their harm, and saw no reason to change course. If we are going to be intellectually honest, we cannot limit our skepticism to sources that we are inclined to distrust. We must also apply the same level of scrutiny to sources that report the viewpoints we are inclined to embrace. And on that note, this episode is long enough so we're going to break here, and continue next week with Part 2. The real poster child for the scandal of documents proving that the fossil fuel companies knew their product was essentially the only significant driver of global warming, and yet did nothing, was Exxon. Exxon scientists, so the articles say, knew all about it, and gave warnings to their executives that went unheeded. That's the subject of Part 2, and I hope you tune in next week.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |