|

|

Probiotics Fact and FictionSome people promote probiotics as a miracle cure for just about anything. What can they really do? Skeptoid Podcast #801  by Brian Dunning "Probiotics" is a word you've probably heard at least ten thousand times over the span of your life. You've heard that it's something you need. You've heard that it will make your body healthier than healthy. You've heard that no living creature could survive without a constant supply of it. One is tempted to wonder how any ancient protohumans, who had no access to a supermarket, could have ever survived without a supply of this supplement that seems so essential. And yet somehow they did survive, as did all the humans who came after them, all the way through history, until the emergence of the health food and fad diet industries in the twentieth century. So right off the bat, we know probiotics — like all supplements — are by no means essential for everyone. So let's turn to the science, and see what they may or may not actually do for us — or to us. We can start by defining exactly what they are, and the UK's National Health Service has a reasonable definition:

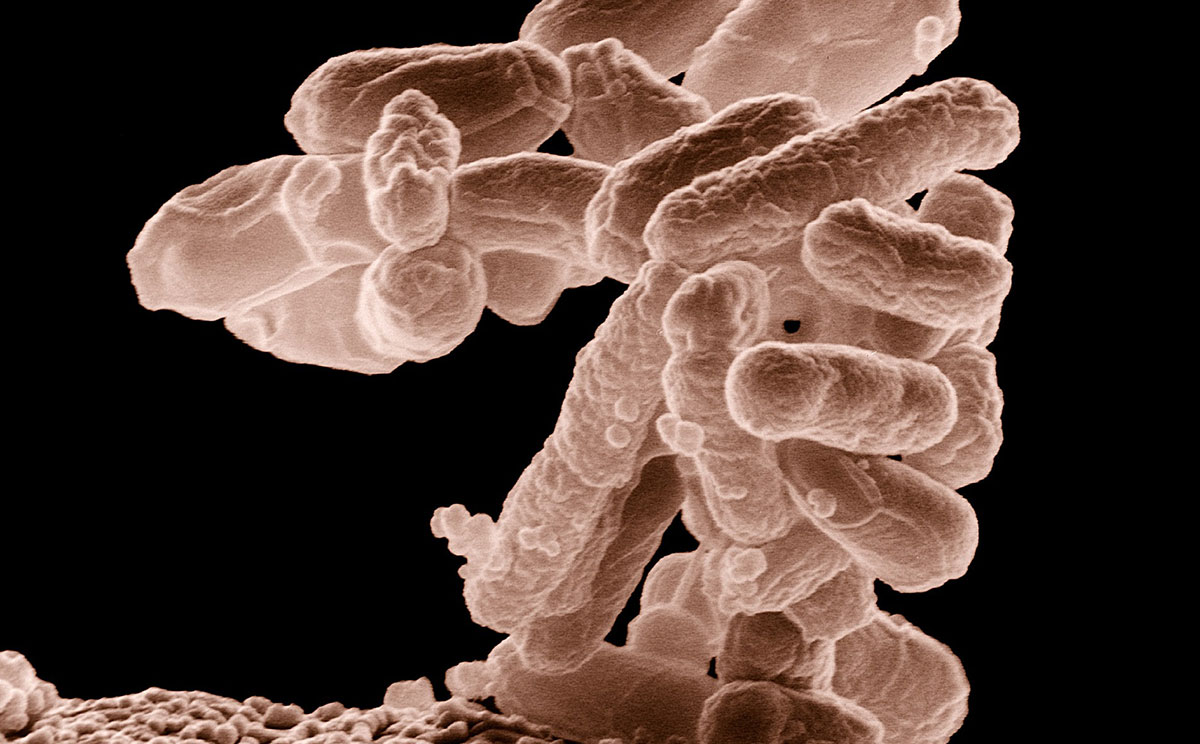

Generally, probiotics are any live microorganisms that are sold as a food additive or supplement intended (or claimed) to provide health benefits. What those health benefits actually are is often vague and not very consistent, but they usually have to do with "improving your gut flora" or "restoring intestinal health," both concepts that presume there's something wrong with your GI tract's bacterial population — which, 99% of the time, means diarrhea or cramping. So what's meant by "microorganism"? Here we don't have to guess, because there's a list. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consists of academics and industry who study and manufacture probiotic products (and prebiotics, which are products intended to stimulate the growth of desirable microorganisms). To them, you can call a product probiotic if a serving contains 1 billion colony forming units of one of five strains of Bifidobacterium, or one of nine strains of Lactobacillus. Those 14 strains of bacteria are the only ones ISAPP feels have a sufficient base of study indicating some contribution to "general benefits." And that, basically, is the entirety of the universe of plausibility around probiotics. There are a couple different types of bacteria that have some experimental support for helping with diarrhea and cramps — but don't jump to the conclusion that chugging down a probiotic yogurt drink will cure either one, because it's not as simple as that. We'll talk more about that in a minute, but first let's dispense with a gigantic constellation of misinformation. And that's that the industry selling you probiotics makes much, much, much larger claims for what their product will do for you. And to sum it all up, the vast majority of it is completely false. In 2020, a group of researchers published a study comparing health benefit claims made by websites against the actual evidence for those benefits, using the Cochrane Reviews as the authority. No great surprise, only 24% of the claims were backed by decent evidence; a further 20% were backed by no evidence at all, basically just stuff the marketers made up; the remaining 56% were backed only by sketchy, low-quality evidence. What does this tell us? If you're playing the percentages, any given thing you might read about what a probiotic can do for you is probably false. That bears repeating: Any given thing you might read about what a probiotic can do for you is probably false. The researchers found that only four conditions — infectious diarrhea, necrotizing enterocolitis, irritable bowel syndrome, and antibiotic-associated diarrhea — are supported by evidence as being treatable with probiotics, although even this is a relatively young science and we don't know everything yet. The list of conditions that are not supported by useful evidence, but for which marketers still promote the use of probiotics, includes ulcerative colitis, pouchitis, Crohn's disease, food intolerance, urinary and vaginal disorders, eczema, obesity and other weight disorders, respiratory disorders, and a whole long list of cancers including colorectal, bladder, liver, lung, stomach, breast, and cervical. It can be very sobering indeed to see just how low some marketers will go to make a buck off of sick people. Particularly insidious are the really vague claims, like "promotes gut health". What does that even mean? First of all, health is the absence of disease. If you don't have a gut disease, you have no reason to be seeking out a treatment. The promise of probiotics is to alter the populations of bacteria in your gut, and if it ain't broke, don't fix it. But let's focus on the positive and see what evidence does show that probiotics can help with. First, we'll look at infectious diarrhea, the usual case of which is acquired by young children at daycare. Its caused by a rotavirus. Acute watery diarrhea can lead to dangerous dehydration. A 2011 review of many studies found that specific strains of probiotic, when administered in specific doses, were generally effective in most trials at reducing the duration of the diarrhea by about one day. Since it's strain and dose dependent, you can't expect to duplicate this success by taking some consumer probiotic product. Second was necrotizing enterocolitis, a very serious condition that affects premature babies. Intestinal tissue gets inflamed and can die, causing a perforation and possibly a fatal infection. The right probiotics can compete against the pathogens and also generate metabolites which the body uses for signaling. This can, in turn, reduce inflammation and regulate the immune cells, among other things. You're not a premature baby so you don't have this, so really, this is one more thing that probiotics cannot do for you. The third condition for which there's some evidence is irritable bowel syndrome, a common condition which leaves you with chronic cramping and gas and inconsistent stools. This evidence is considerably less robust, and from reading the studies and the reviews of multiple studies, it seems clear that there's still no consensus on what works best. A nice thing about consumer probiotic food products and supplements is that they're not going to hurt you when taken as directed; so if you have irritable bowel syndrome, there's no harm in attempting to self-medicate by trying them. You might get lucky, you probably won't, and you'll definitely spend money in the attempt. The fourth and final condition for which there's evidence worth speaking of is antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD). The doctor prescribes you antibiotics for some infection, and a side effect is that most such antibiotics will kill off some percentage of your gut bacteria. And when that population gets thrown out of whack, your bowels' normal processing of waste is interrupted, and diarrhea is often the result. Diarrhea is always something to keep a close eye on because of the potential for dangerous dehydration, so AAD is something prescribing doctors are always aware of. Again, it is noteworthy that zero out of these four are "general gut health", and all four out of four of them are diseases you probably don't have. But let us not leave the hopeful listener empty-handed — or, empty-boweled, as it were. Suppose you have some other issue in your bowels, more of a generic diarrhea, for example. Suppose you have C-diff, more formally a Clostridioides difficile infection. This is a "bad bacteria" that can grow out of control if you don't have enough "good bacteria" keeping it in check. C-diff doesn't just randomly happen, so it's almost certainly not the cause of just an ordinary case of diarrhea you might get after a funky dinner or something. When C-diff does happen, it's most often after AAD, when your gut flora is left a bit out of whack following a course of antibiotics. Do probiotics help in these cases? So far, the answer is no. But what does help — in fact, it appears to help about 90% of the time — is a fecal transplant. This is poo from someone else — a healthy person — transplanted into your intestines, usually with a colonoscopy or enema, or by way of a pill filled with dried-up powdered poo. Far from a probiotic, which is just one type of bacteria, a monoculture if you will, a fecal transplant delivers a full dose of the full spectrum of thousands of species of bacteria from a healthy gut. It doesn't take much to see why this would be so much more effective. It's a full system reset from out-of-whack to healthy, rather than a probiotic which takes you from out-of-whack in one direction to out-of whack in another. But getting even that benefit — if you consider it one — is a roll of the dice. Various types of probiotic supplements are intended to deliver, in each gram, between 1 million and 100 million living cells in order to be effective. And, as we've just discussed, "effective" is a somewhat elusive goal for a probiotic. But it means for the newly introduced strain to take root and flourish, and the reason for the big range of numbers is that those 14 strains of bacteria all have different tendencies to grow. But this number is measured at the time the product is packaged for retail. Then there is the time for transportation, storage, retailing, more transportation and logistics, and finally the time it sits in your cold fridge. This is the big dirty secret of probiotic retail food supplements and products. All hundred million per gram of the little guys may have been alive when it was packaged, but how many of them are still alive when you get around to consuming it, potentially weeks later? It is fewer. It is always fewer. How many fewer is different in every case, but sometimes it's zero. Probiotics begin dying even before the packaging is complete, and they continue dying until you consume them. Every time you consume a probiotic product, it's a game of roulette. The number of living cells in that product is anywhere between zero and what it was originally intended to be. And so in summation, I really can't find any compelling reason to take a probiotic. The only things for which there is any evidence it might help you with are a tiny number of diseases that you almost certainly don't have; and if you do have them, there are better treatments available. But I'm not dismissing probiotics completely. They are biologically plausible as a treatment, as we can see with their effectiveness against child infectious diarrhea and necrotizing enterocolitis — assuming we take the right type in a prescription verified dose. Maybe tomorrow they'll be found to be an effective treatment for something regular people might have; and in the meantime, they aren't going to hurt anyone. So don't get too worked up about probiotics, but also don't flush them out with the poop.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |