|

|

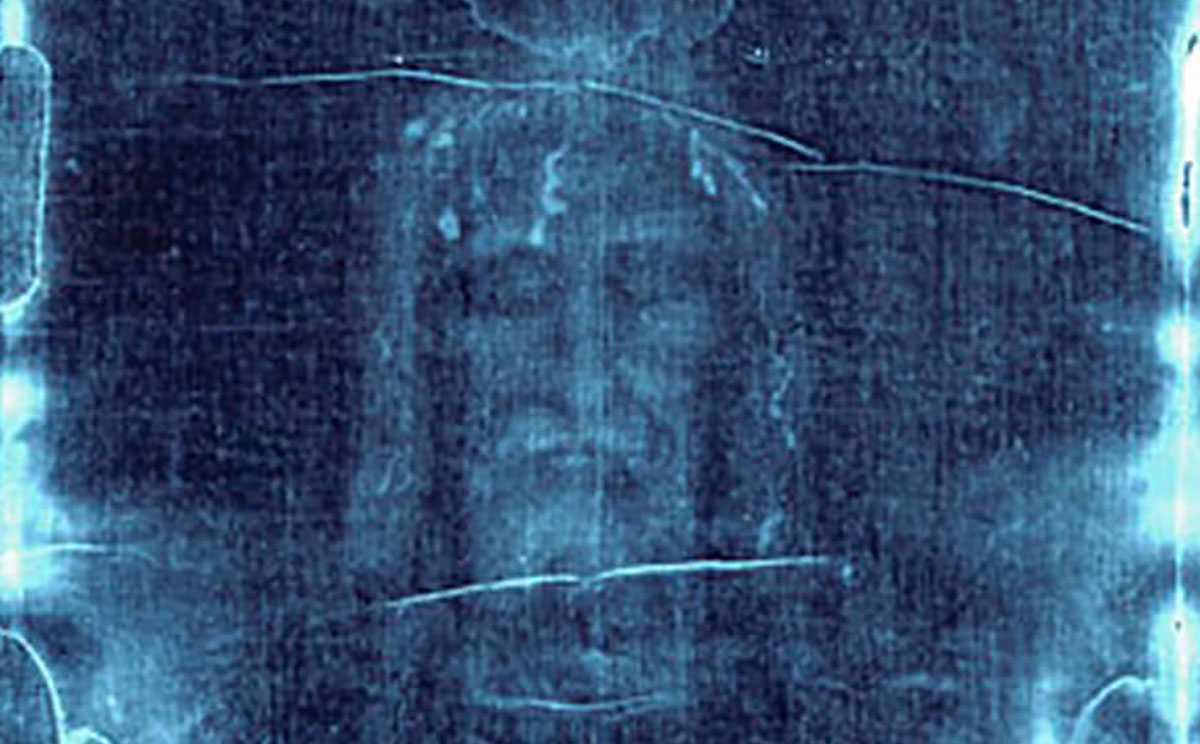

What Made the Shroud of Turin ImmortalSkeptoid Podcast #795  by Brian Dunning Most everyone has heard of the Shroud of Turin, the famous piece of fabric that lay on the face and body of Jesus in the tomb, and that — two thousand years later — is said to still bear his imprinted image. And if you have heard of it, you've almost certainly also heard that simple radiocarbon dating has proven that it cannot possibly be real; it's from the 13th century at the very earliest. So you might wonder why it would even warrant a Skeptoid episode. The reason is that neither of the those two perspectives — that it is real, and that it is fake — come close to telling the full story of the Shroud. For its true history is rich with lessons in how and why we believe — and it is within those deeper parts of the story that we learn why it remains such a profoundly entrenched part of the human experience. The Shroud itself is an actual, physical, extant piece of linen, four and a half meters long and just over one meter wide, stored at the Chapel of the Holy Shroud in Turin, Italy. It is traditionally believed by many Christian denominations to be the actual cloth which, according to the Bible, was used by Joseph of Arimathea to wrap the body of Jesus of Nazareth after his death by crucifixion, with the permission of Pontius Pilate, in accordance with Jewish law that forbids dead bodies from being left exposed overnight. In the gospel of Mark, Joseph — who had been on the council that condemned Jesus, but still wished to follow Jewish law — did the minimum necessary to wrap the body in a new, clean shroud and place in into a tomb carved into the rock. This was the tomb from which Jesus is said to have resurrected himself after three days, and during those three days, it is believed that the image of his face and body became imprinted onto the fabric, and this image is still visible today. The disciple Peter retrieved the shroud after the resurrection. We'll get into the known history of the Shroud now in Turin once we better define the question we're here to answer today. In order to have this conversation, we must first dispense with the enormous boulder that's blocking our doorway; and that's that it's premature to answer the question of whether this shroud really did cover Jesus of Nazareth, without first establishing whether Jesus of Nazareth existed. Woe be unto short-memoried or new listeners; we dove all the way to the bottom of this question in episode #666 — of course — and found that, despite loud contradiction from both the for and against sides, the majority of academic work does not find sufficient evidence to answer this question one way or the other. But it's also a really specific question, because of all the messiahs running around that part of the world at that time, there could easily have been half a dozen who happened to be named Jesus. For the purposes of that episode, our specific question was whether a Jesus of Nazareth was executed by Pontius Pilate, in or about the year 30 CE, as that's a factual question that does have a firm yes or no answer. That answer is just not known. But for the question of the Shroud, we can be less restrictive. If this piece of fabric had lain over anyone's face at all two thousand years ago, that would be a remarkable enough discovery. If it was over the face of someone named Jesus who had been regarded as a messiah, even more so. But to prove it covered the body of Jesus of Nazareth after his execution by Pontius Pilate in or about the year 30 CE... well, this is unprovable. We don't have DNA from Jesus to match with the stains on the cloth said to be blood, and the bloodstains have been chemically identified as tempera paint, and so don't contain any DNA. So, for the purposes of this episode, let's make our litmus test simply the question of whether this is indeed a two thousand year old burial shroud bearing the image of the person it covered. Its first recorded appearance in history was not a promising one. In 1353, six clergymen quite suddenly appeared in Lirey, France where they built a small wooden chapel and began charging admission to see what they advertised as the "Shroud of Christ". Local clergy condemned it from the beginning; for one thing, never before in the history of Christendom had there been any mention of an imprint visible on the burial shroud recovered by Peter; for another, an unnamed artist had freely confessed to having been commissioned to paint the image. Nevertheless this little enterprise was successfully carried on for decades, and some researchers maintain it is the very same Shroud that lies in Turin today. So now let's look at the scientific testing that's been done on the Shroud. To start with, the Catholic Church has long been (understandably) reluctant to allow independent analysis of its relics, as so many have been easily proven to be fake under the scrutiny of modern science. And, when they do permit research, it's almost always done by a special commission of Catholic scholars appointed by the Church itself. And such was the case with the Shroud of Turin as well, with the most infamous iteration being a group called STURP (Shroud of Turin Research Project) which, during the 1970s and 1980s, consisted of dozens of scientists from all around the world, many of whom held important appointments at such labs as Los Alamos and the US military. Nearly all were staunch Catholics and many had been defenders of the Shroud's authenticity for decades. STURP included no experts in relevant fields like ancient fabrics. And, predictably, their research was "inconclusive". Finally, after years of negotiation, the Vatican permitted radiocarbon testing to be done, despite objections from the STURP scientists. Debate over the protocols dragged on for years, with the laboratories demanding scientific autonomy, and the Church and STURP demanding more control. Finally a protocol was agreed, and — to make a long story short — carbon-14 dating at three labs in Oxford, Zurich, and Arizona in August, 1988 all independently proved that the Shroud could not possibly be any older than the 13th century. One of the problems with the protocols was that no authentic fabric could be found to be used as a control. The Shroud of Turin fabric is a herringbone weave, which was unknown in that part of the world until many centuries later (though fragments of herringbone fabric have been found in much older archaeological sites, such as the peat bogs of Ireland). This nonexistence of comparable fabrics was a strike against authenticity even before the testing began. Church scholars have objected to the radiocarbon results ever since, raising essentially the same arguments against the reliability of radiometric dating made by Young Earth Creationists who attempt to prove the Earth is only 6,000 years old. None of these objections has ever withstood any scrutiny. Let us now turn to the earliest recorded account of the Shroud. It comes from a French Crusader Knight named Robert de Clari in Constantinople, during the Fourth Crusade in 1203. He reported that every Friday, a local church displayed the Shroud, showing the figure of Jesus. Until this Crusade, Constantinople had been the capital of the Byzantine Empire, and upon its fall, one of the former emperor's nephews, Theodore Angelos, wrote a letter to Pope Innocent III protesting the Crusaders' attack. In his letter, he included a mention of this same Shroud among all the other treasure the Crusaders had looted from the city. So now it's important to recall the Knights Templar, and we covered this in pretty good detail in Skeptoid episode #508 on the true history of the Templars. They were one of many monastic orders created by the Pope to defend and secure the lands seized in the Crusades, and for funding, these orders all relied on donations from wealthy patrons. Attracting these patrons has been aptly compared to rush night among college fraternities, when they all compete to pull out all the stops to show the desirable candidates how much better their fraternity is than all the others. To do this, the Templars, the Teutonics, the Hospitallers, and all the other such orders touted the vast treasures they'd accumulated and especially the rare holy relics they held. How about something extra special, like the burial shroud of Jesus himself — only this time it's not just a linen cloth; this one has a full image of the Savior imprinted on the very same fabric that touched his skin? Never mind that never before in Christendom had any mention ever been made of such a thing — even the original Biblical account makes no reference to Peter finding any such image when he collected the fabric. That part of the story, which is what made the Shroud immortal in the eyes of Christians worldwide, and is what undoubtedly inspired the six clergymen to paint and charge admission for their own Shroud, is the important part. Because the two earlier parts — Robert de Clari's report of seeing the Shroud in Constantinople, and Theodore Angelos' letter to the Pope complaining of having it added to the Templars' mythical treasure stash — are both fake. Angelos' letter has been conclusively proven to be a modern forgery (and even if it wasn't, he hadn't been born yet when it was purportedly sent); and though historians don't think Robert de Clari was lying, it's generally agreed that he was mistaken, having heard of a different item — an acknowledged painting called the Image of Edessa — and mistakenly reported it as Christ's burial shroud. What survived all of this was a story of a burial shroud miraculously imprinted with Christ's image, a story that no doubt inspired the six clergymen in Lirey, France in 1353 when they hired the local artist to create for them what they essentially displayed as a sideshow curiosity. Whether theirs was the same shroud that eventually made it to Turin in 1578 is dubious, but also unimportant. By any reasonable standard, the Shroud is a medieval story that has no credible connection to to either the cloth in Turin or any of its other manifestations at various places, and certainly no credible connection to anyone in Jerusalem more than a thousand years earlier. The significance and personal import of that story is a matter for every individual according to their beliefs and preferences — but the facts of it are not.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |