|

|

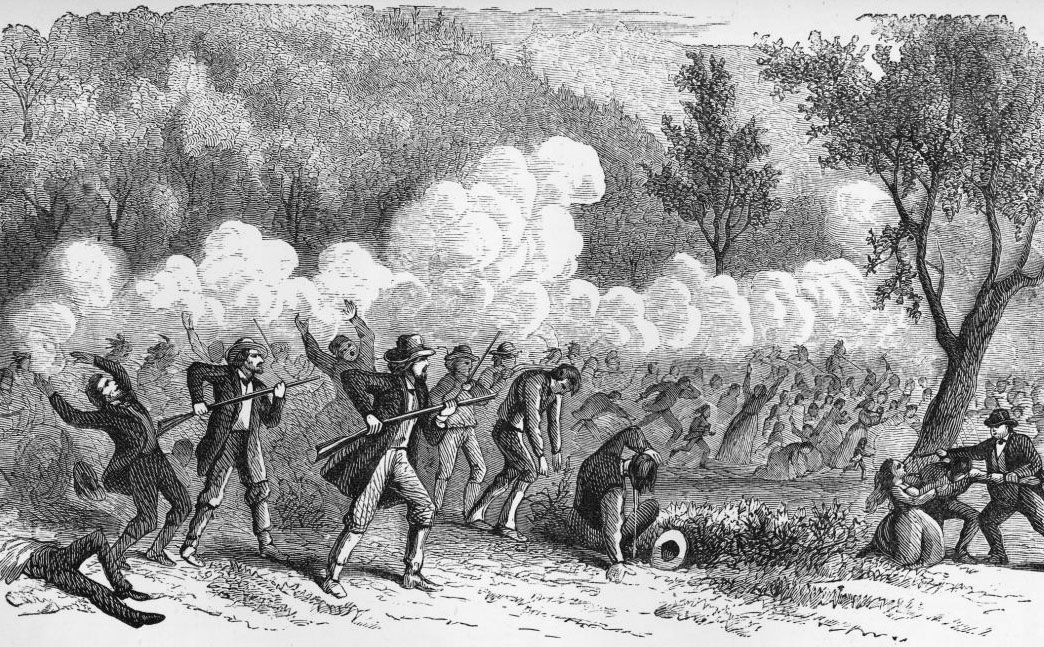

Inside the Mountain Meadows MassacreMyths, conspiracies, and coverups cloak this 1857 massacre of American emigrants. Skeptoid Podcast #768  by Brian Dunning When a wagon train of emigrants met its bloody end in Utah in 1857, it launched over a century of lies, coverups, conspiracy theories, and inquiries. Today, when you hear the Mountain Meadows Massacre mentioned, it's likely to be in the context of the Mormon Church exterminating non-Mormons from its territory; or perhaps a colorful story of white men disguised as Native Americans to conceal their mass murder; or perhaps a cloak and dagger tale of anti-Mormon terrorists sneaking into Utah to poison the wells and cattle of the faithful. There's hardly any possible version of this story that hasn't been told at some time by someone. But regardless of the details, September 11, 1857 ended with some 120-140 emigrants dead, their bodies literally left to the scavengers on the open meadow. Today we're going to have a look at what's known and what's not known, and hopefully dispel some of the myths around this horrible historical massacre. It's best to start out with appropriate modern context and acknowledge that the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (aka the Mormons) issued a "statement of profound regret" — if not an apology — for the massacre, in 2007 — 150 years to the day after it happened. In it, they fully and frankly recognized that it was committed by Mormons:

These facts as stated do conform the mainstream secular historical view, so there is no longer any doubt or dispute over who committed the massacre — though it took a century and a half for that to be acknowledged. Yet while that largest question is now finally at rest, other questions — including who is ultimately responsible — do not have such a clear answer. In 1857 the Utah Territory was, for all practical purposes, a theocracy. While it had all the official trappings of a United States Territory, its civic, judicial, law enforcement, and militia leaders were almost all church officials. The laws and courts of the United States existed, but the only law that anyone paid attention to was that of Brigham Young: Prophet and President of the Mormon Church, Governor of the Utah Territory, and by all accounts, probably one of the most capable and commanding personalities the world has ever known (in addition to being a serial rapist of multiple underage wives*). And squarely upon his shoulders rests the biggest question we need to answer today: Did Brigham Young know about, or perhaps even order, the Mountain Meadows Massacre? Or, was it the action of a few rogue individuals? The best way to make this determination — or more accurately, to determine whether we'll be able to make such a determination — is to start by looking at the sociopolitical context in which the massacre happened. It's well known that the Mormons had an uneasy relationship with the "Americans" — the Mormons' term for everyone else. The history between the two had been bloody. 22 people had died, including Mormon apostle David Patten, in the 1838 Mormon War between Mormons and the people and militia of Missouri, and there had been any number of small skirmishes and acts of violence as the Mormons emigrated from Missouri to Illinois. There, church founder Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum were lynched. Next, in Arkansas, church apostle Parley Pratt was murdered. Indeed, Pratt's death came just a few months before the massacre, and hatred for the people of Arkansas simmered hot in the collective Mormon heart. It was not at all insignificant that the victims of the massacre, the 120+ members of the Baker-Fancher Party, were from Arkansas. But the single greatest boiling point was the specter of impending war with the United States. What's now known as the Utah War was just getting underway. This was a mostly cold, tactical standoff between Mormon militia and a number of US Army regiments. In a nutshell, the Army had come to squash the Mormons' contempt for American laws. Polygamy, practiced by the Mormons, was a major issue. So was the Mormons' increasing belief that they were a sovereign state, and their general ignoring of federal statutes in favor of their own theocratic system. One month before Mountain Meadows, Brigham Young declared a state of martial law. Its provisions declared:

In short, tensions were as high as they could possibly get. When this declaration was issued, the Baker-Fancher Party had already arrived in Salt Lake City for their planned restocking — though only by a day or two. They found the Mormons unwilling to sell them grain. They were lucky to make it out of town; many Mormons considered it their religious duty to exact revenge for the Arkansas murder of Pratt just weeks before. They left quickly, hoping to buy the needed supplies at Cedar City, 250 miles south. But upon arriving there, they found their welcome was even worse. Rumors about the Baker-Fancher Party had arisen. Among these was that certain members had, while in Salt Lake City, boastfully flaunted the actual gun that had killed Joseph Smith. Another was that among the party were militia who had fought the Mormons in the Haun's Mill Massacre during the Missouri Mormon War. One story was that Pratt's wife had been in Salt Lake City and had recognized her husband's murderers among the emigrants. Yet another rumor, reported as fact, was that on the way from Salt Lake the party had poisoned a water supply at a place called Corn Creek, killing a number of cattle and a few Mormons who ate their meat. Historians regard all these rumors, and others, as false. Yet they had the intended effect. Church leaders in Cedar City and nearby Parowan — who also happened to be the militia leaders — gathered to discuss how to deal with the Baker-Fancher Party; by Brigham Young's declaration, it was there illegally. The prevailing view was to have Paiute natives slaughter the party. The Mormons and Paiutes were allied in their resistance to the approaching American army, and it would be easy enough to persuade the Paiutes that the Baker-Fancher Party was an American advance. However support for this plan was not universal, so a rider was sent to Salt Lake City to get definitive orders from Brigham Young. There was no telegraph and it was a six-day round trip ride. Having escaped from Cedar City, the Baker-Fancher Party stopped at an area of fine grassy pasture, suitable for camping for several days while their cattle could graze, called Mountain Meadows. History records nine Mormon leaders as being most responsible for the massacre. One of these didn't want to wait six days. He took a party consisting of an unknown number of Paiutes plus an unknown number of militia disguised as natives, and besieged the wagon train. The gunfight lasted five days, during which seven emigrants were killed. The tipping point came when two of them tried to make a break to get fresh water. One was killed; the other made it back, but not before seeing that his attackers were white men. When news made it back to Cedar City that their disguise had been blown, the Mormon leaders concluded they had no choice but to leave no witnesses. At that point, the Paiute ruse was dropped, and undisguised militia finished the job. The murders were singularly cold-blooded executions. The emigrants were divided into three groups, each of which was marched away from the camp on foot separately. One group consisted of all the adult men, and each was guarded one-on-one with a militiaman. At the shout of an order, each militiaman leveled his gun and executed his man, all at once, and the bodies were left where they fell. There was no battle or siege or fight. In all, as many as 140 were murdered, leaving only seventeen children alive, all under the age of seven. Several days later, the rider returned from Salt Lake City with Brigham Young's reply, devastatingly dated September 10, only one day before the massacre was concluded, and thus at least two days by horseback too late. Brigham's orders read, in part:

Taken together with the other evidence, this letter informs the prevailing opinion among historians that neither Brigham Young nor any of the most senior church officials either knew about or condoned the Mountain Meadows Massacre. It's also generally accepted that Brigham would have stopped it if he could have. Quite a few massacre participants were excommunicated from the church. Nine were criminally indicted for murder or conspiracy — not insignificant since the church and Utah's legal system were essentially one and the same. However only one man was convicted; and though he was the one most directly responsible and was executed, the lack of additional convictions seems a clear dereliction of duty by the church. There are some theories that Brigham's original letter — which does not survive — may have also contained other instructions that perhaps did give more license to the murderers than is known. Another theory, as asserted by the man who was executed, was that Brigham had given standing orders for any such parties to be wiped out. Both theories are without evidence. Nevertheless, most historians still lay the ultimate blame for the massacre on the church itself, and on Brigham Young, for having created the conditions which drove the men of Cedar City. This much larger question of judgement is one that this podcast does not take a hand in, but rather, these are the basic historical facts for the philosophers to do what they will with. * Addendum: I did anticipate that there would be negative blowback, mostly from Latter Day Saint listeners, to my apparently-gratuitous comment about Brigham's underage wives. I prepared a response to such feedback here. —BD

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |