|

|

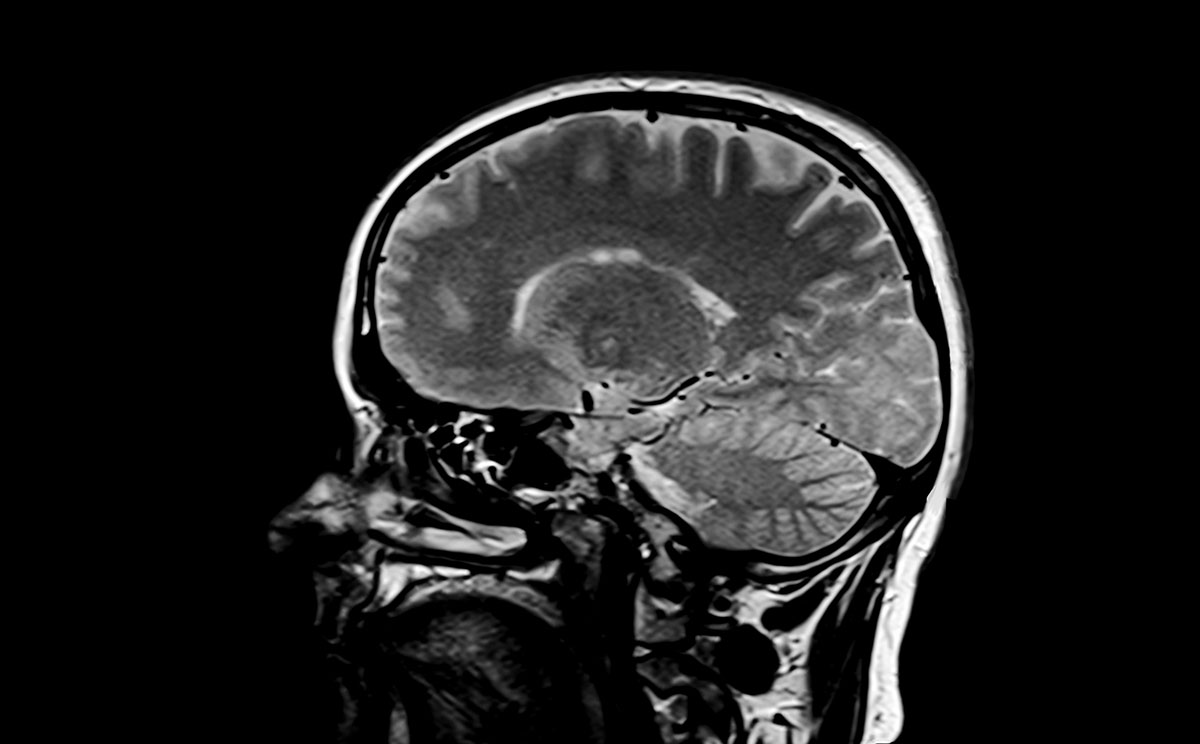

Learning Languages from Brain InjuriesSkeptoid Podcast #716  by Brian Dunning Today we're going to dive into one of those urban legends that we've all heard about many times, and see just how much truth there is to it. It's the claim that some people, upon waking up from a coma or after having a stroke, suddenly speak a whole new language — often one they did not speak before, or perhaps had only been just beginning to learn. It seems unaccountable. Is it possible that we overhear just enough random snippets of foreign languages that our brain stores them away, well enough that it can construct a whole new speaking ability to replace the one lost due to the stroke, or other brain injury? Today we're going to point the skeptical eye at these cases and see exactly what's really going on. One reason we've all heard about these cases is that they're reported in the news all the time. In 2010, a popular news story claimed that a teenaged Croatian girl woke from a coma understanding only Croatian but speaking only German as fluently as a native, despite only having just begun to learn German in school. A German translator had to be brought in so she could communicate with her family. In 2014, it was widely reported that a 25-year-old man who had suffered a head injury and was put into an induced coma awoke with a newfound ability to speak perfect, fluent French. He also thought he was actor Matthew McConaughey. He eventually recovered from his injuries, but retained his fluency in French. In 2016, a teenager in Georgia suffered a severe concussion in a soccer game that put him into a coma for three days. When he awoke, he had lost the English language but had gained another: he was speaking in fluent Spanish, a language it was reported that he'd known only a few words of. Eventually he recovered his English skills. Such cases as these go on, and on, and on. Despite the Internet apparently bursting at the seams with a huge number of these cases, they're actually quite rare; rare enough that there aren't really any large studies published. Instead, what we have are a lot Internet anecdotes from which we can't draw any conclusions, and a much smaller number of individual cases that have been studied in any detail. And for these cases, we have pretty good answers for what's going on. For these instances, we find that the popular reporting of each is typically grossly exaggerated. For example, the reports often say the person suddenly became fluent in a language they had barely studied, when in fact we don't find any cases where people actually knew more of a foreign language than they knew before their injury. Other reports say the person developed a perfect foreign accent for some language, but in fact we don't find any cases where the patient's new accent is actually a good representation of the reported foreign accent. Contrary to the way these stories are usually reported, these cases are not gains of new abilities; but rather losses of old abilities. Allow me to proactively head off some anticipated feedback, which is that some of you have seen articles on the Internet where someone's stroke, injury, or coma caused them to suddenly speak perfectly in a language they had no prior experience with. These stories are being falsely reported. Consider that you're reading them on the Internet, and not in an academic journal on neurology. The verified cases fall into either one of two camps: Foreign Language Syndrome and Foreign Accent Syndrome. They are just as their names suggest. Foreign Language Syndrome is where the patient stops speaking their usual language and instead relies on a secondary one; Foreign Accent Syndrome is when the patient continues speaking their normal language but apparently in a foreign accent. Let's talk about this first. Foreign Accent Syndrome (FAS)Although this is almost always reported in the pop media as someone gaining a foreign accent, in fact what's happening is a deficit or change in the articulation of speech, which is then misinterpreted by unsophisticated listeners as a particular foreign accent. FAS is most often observed in patients who have had a stroke or other brain injury, so what's happening here is an alteration in the way the muscles of the mouth and jaw express speech. Listeners may perceive it as a foreign accent, because the changes are not always simply slurring, like you might expect with a pronunciation deficit. Instead, the changes are usually more nuanced: changes in syllable stress, substitution or deletion of certain consonants, and vowel sound substitutions and additions. These are the same kinds of distortions that distinguish actual foreign accents, so it's understandable why so many family and friends of the patient make this interpretation. The non-verbal characteristics of speech are called prosody, such as rhythm, intonation, and syllabic stress. So when this condition was first described around 1940, it was called dysprosody. In the rare cases that a dysprosody just happens to sound to someone like a particular foreign accent, then we call it FAS. Here are three well-publicized cases where the patients' new speech patterns do strongly sound — to speakers of their native language — distinctly like specific foreign accents. Here is an English woman who sounds French: And here is an Australian woman whom people think sounds Eastern European: And here's another English woman who sounds a lot like a stereotype of a Chinese accent: Lest you suspect these people are faking it, the answer is no, not in these cases; as they're all under the care of neurologists and their brain injuries were real. However there is a variant with a purely psychiatric cause, called Psychogenic Foreign Accent Syndrome. In rare cases of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or related disorders, some patients may speak in a foreign accent over the course of a psychotic episode, which then goes away once the episode is over. Although the patient is doing this deliberately on their own, it's not really accurate to say they're faking it, as it's a symptom of a legitimate psychiatric condition. More common than FAS are brain injuries that hamper speech ability to the point that it sounds slurred and hard to understand, but because that's easily recognized for what it is, people don't tend to make the same "foreign accent" association. These represent the vast majority of speech deficits resulting from a brain injury; it's much rarer for the injury to knock out such specific parts of the brain that the ability to speak is not hampered, but that there are noticeable changes to certain vowel or consonant sounds. In fact, it's so rare that one estimate says there are probably only about 100 people in the whole world who have this. Foreign Language Syndrome (FLS)The fascinating thing about this is how it illustrates the complexity of language in the brain. Think of all the many tasks language requires: comprehending words that we hear or read, calling up needed words when we speak or write a sentence, structuring a sentence properly, deciphering the structure of sentences we hear or read, all the motor skills required to speak or write, the ability to translate back and forth between complex subjects and spoken or written language. Impairments of these abilities are called aphasias, and they come in many, many forms. Any one, or several, of these compartmentalized abilities can be impaired or even lost, and these impairments can be short-term or permanent. Aphasias are caused by brain injuries, which can be a stroke, head trauma, brain tumor, or an infection. Sometimes these conditions can also trigger a coma, which is why media reports of FLS often say the patient awoke from a coma with this new strange foreign language ability. There is still a lot we don't know about how the brain processes language, but one theory that seems to be pretty well supported is that fluent use of a native language involves different parts of the brain than the use of a second language that's not yet fluent. Imagine how effortless it is to speak in your native tongue, then compare it to how you might piecemeal out a sentence in a new language you're just learning, pausing to track down translations of words that you first think of in your native language. But things get a lot more tricky with patients who are fluent in multiple languages and then suffer an aphasia. This is called bilingual aphasia (even when the patient is multilingual, the term bilingual is typically used clinically, because reasons). Sometimes the primary language is affected, sometimes the secondary language is affected, and sometimes both equally. It's about twice as common for multilingual aphasics to lose their abilities equally across all the languages they know than it is for one to be left intact. In rare cases, it's the separation between fluently spoken languages that is lost, leaving the patient involuntarily mixing languages together when speaking. One theory for why these patients are always described as speaking "fluently" in their second language — a language they had not yet developed fluency in — is that the brain's loss of the first language eliminated a slow process that had existed before. Previously, when they had just been learning the second language, they would need to think of the sentence first in their first language then deliberately look up the translation for each word. With the first language gone, this slow process was no longer possible, so the second language would flow more easily than before. However it's important to note that no new words or grammar rules would have materialized out of nowhere; the patients were simply able to speak somewhat faster than they could before. The important detail of Foreign Language Syndrome, at least for our purposes today, is that reports of someone spontaneously learning a new language as the result of a coma — or suddenly knowing more of a language they'd just begun to study or only overheard a little being spoken — are false. The clinical literature is devoid of any verified cases, and none are known to science, despite numerous such claims on the Internet or in the pop media. But can these people recover? The answer is "sometimes". There are a number of factors that influence a patient's ability to recover from an aphasia, including age and language proficiency. People who speak multiple languages tend to have better recovery outcomes than monolinguals, probably because their brains start out already more experienced at learning language functions. When recovery does happen, it can be just as unpredictable as the original injury. Some specific abilities may recover and not others; multilingual patients may recover one language and not the other, or may recover them in succession or in parallel; the languages themselves may recover but not the ability to keep them separate; and there have even been cases where patients can only speak one language or the other, sometimes on alternating days. The brain is a strange and complex place.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |