|

|

The Mystery of the Ellen AustinThe true history behind one of the Bermuda Triangle's strangest legends. Skeptoid Podcast #699  by Brian Dunning Today we're going to weigh anchor and have a look at one of the enduring mysteries of the sea. It's the tale of the Ellen Austin, a 19th-century sailing ship that brought emigrants from Liverpool to start a new life in America. The tale has become one of the cornerstones of Bermuda Triangle mythology. In early 1881, the Ellen Austin encountered a phantom derelict adrift in the Sargasso Sea, and the terrifying events of the next few days cost the lives of many of its crew and became the stuff of legend. In this episode, we're going to unravel the story down to its bare facts, and see if we can determine whether it was literally true as reported, or if the story might have perhaps grown a bit over more than a century of retellings. First, let's have a look at the story as it's popularly told. This is what you'll find on most websites and books relating the spooky tale of the Ellen Austin, and the phantom ship that confounded it. Depending where you read it, some of the details (large and small) will be different, but this is the basic plot:

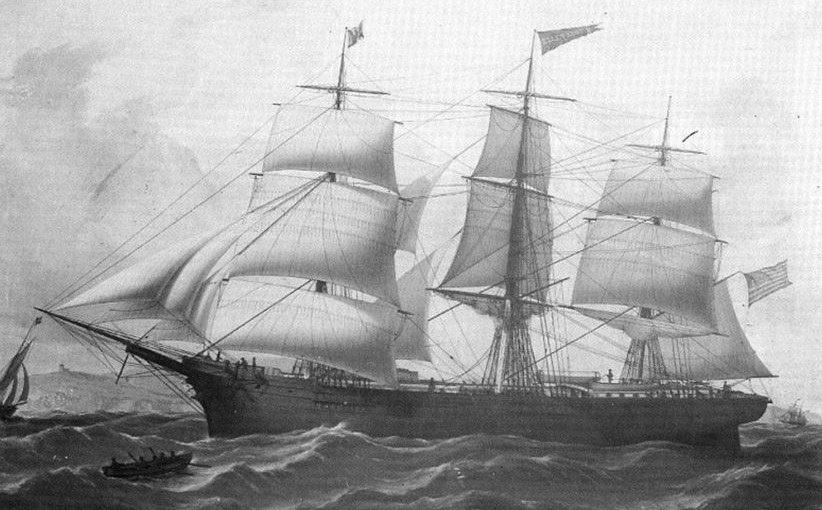

The Ellen Austin did indeed complete its voyage, docking in New York on February 11, 1881. This is according to Lloyd's of London, whose records tell us some of the basics of the voyage. Its captain was A. J. Griffin (wrongly given as Baker or Garrick in some accounts); its destination was New York (wrongly given as either Boston or Newfoundland in others). Other details of the story are not found in any known official record and vary widely depending on where you read the account. Either one or two prize crews were lost; some say the storm came before the fog, or the fog before the storm, or only one or the other; some say this happened in August of 1881 instead. We can eliminate this last variation, as this was the ship's last voyage as the Ellen Austin. After this trip, it was purchased by a German company and renamed Meta. Some accounts describe the Ellen Austin as either a brig or as a schooner; but according to a painting of it that I found, it was neither; it was a full-rigged ship. This is more in line with expectations for such a large vessel: Ellen Austin was 210 feet long and displaced 1,812 tons, even bigger than the huge Star of India in San Diego, if you've ever visited that. Some say it was British owned; it wasn't, it was owned by the American firm Grinnell, Minturn & Co., the same owners of the famous Flying Cloud clipper ship. With such limited hard facts available and so much radical variation in the ghost story-style accounts found on all the Bermuda Triangle websites, one wonders how we can hope to get to the bottom of this one. Fortunately we can follow the sagely guidance of that great barrister, Samuel T. Cogley, attorney at law, who gave us his famous advice: "Books, young man; books!" The first thing we learn when going back into the literature written before the Bermuda Triangle mystery tainted so many tales of the sea is that a fundamental of the Ellen Austin story has a very plausible basis. Although we've all heard stories like this one and that of the Mary Celeste which suggest that a derelict vessel would be a rare and remarkable circumstance, that wasn't the case. In 1894 the US Hydrographic Office published a 25-page report titled Wrecks and Derelicts in the North Atlantic Ocean, 1887 to 1893, Inclusive: Their Location, Publication, Destruction, Etc. In just those seven years — closely after the Ellen Austin story is said to have taken place — the report's author, then Commander (and later Rear Admiral) Charles Dwight Sigsbee, found 482 identified and 1,146 unidentified vessels floating about the North Atlantic. They were in all states of repair; some severely damaged and capsized, and many others had simply become grounded, were abandoned, and later naturally refloated with the tide. Sigsbee noted that groundings on the sand banks off the United States' eastern coast was the most common origin of the derelicts in his report. Some of them would drift thousands of nautical miles; some would circulate in the Atlantic currents for years. With 1,628 derelict ships in the area, it should hardly be surprising to anyone that this most basic story element of the Ellen Austin tale — that of encountering an uncrewed derelict ship — could easily be true. In fact there was even at least one well-publicized precedent for encountering not one, but two abandoned but perfectly seaworthy vessels in a single voyage. In March of 1873, the New York Times published an account of the bark Abd el Kader. Crossing the Atlantic toward Boston, the ship first came upon the Robert C. Winthrop, with water in the bilge but otherwise in sailing condition. Only a few days later they encountered the schooner Kate Brigham in seaworthy condition and still fully laden with a cargo of petroleum. As this story was published in the Times, it's possible that it became well-enough known to have inspired later tall tales. The second thing we learn from actual books is that the Ellen Austin tale's inclusion in Bermuda Triangle mythology really highlights the lack of original research done by so many modern paranormal authors — indeed, even the lack of basic fact checking. Sailing routes from England to New York in the 19th century took the short route west across the north Atlantic. Even though this fought the prevailing westerlies head-on — especially in the winter when the Ellen Austin made its most famous trip — this was still faster than going south to cross over and then taking the long trek north. Ships tacked into the wind and inched their way across; Ellen Austin's two-month crossing was the rule, not an exception requiring a weird diversion with a phantom derelict to explain it. This route was far, far north of either the Bermuda Triangle or the Sargasso Sea. Thus, that the Ellen Austin met a drifting schooner in the Sargasso Sea is certainly false, and the whole tale's inclusion in any Bermuda Triangle mythology is entirely incongruous. The first appearance of the Ellen Austin story in print seems to be one from 1906 in a South Dakota newspaper — oddly enough — the Daily Deadwood Pioneer-Times. The short paragraph gave only the name of the ship, the year (wrongly as 1891), the vanishings of the two prize crews, and no other details. That omission of other details is important, as the most influential telling of this story came from a 1946 book, The Stargazer Talks, summarizing the radio broadcasts of Lt. Commander Rupert Gould, who told a version of the Ellen Austin story in October 1935. We would not be too far off to guess that the Deadwood Pioneer-Times blurb was his only source — for the reason that all other details he gave in his radio broadcast were wrong: the name of the captain, the ship's destination and ownership, etc. The most likely reason they were all wrong is that Gould made all of them up to flesh out the story. It wasn't until later authors began to apply modern research techniques, like microfiche searches of old records, that we began to collect the true details which are mixed in with the wrong details in today's Bermuda Triangle versions of the story. However, we can speculate all we want about this — there is one more fact given in the Lloyd's of London records that tells all we need to know about the Ellen Austin and the phantom derelict and the vanished prize crews. According to Lloyd's, the number of casualties suffered by the Ellen Austin on the 1880-1881 voyage from Liverpool to New York was — wait for it — zero. Everyone who boarded the ship made it safely to New York. There was no first missing prize crew, and certainly no second missing prize crew. Whether the Ellen Austin did encounter a derelict ship on that trip is not recorded in any surviving contemporary documents, but it's certainly perfectly plausible. So far as any of the other details of the story go, they are certainly perfectly fictional — the nameless phantom derelict and its tendency to gobble up prize crews and send them to Davy Jones' Locker is just another astonishing tale of the sea. Correction: An earlier version of this incorrectly described the North Atlantic's prevailing westerlies as trade winds. Trade winds are equatorial east-to-west winds. —BD

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |