|

|

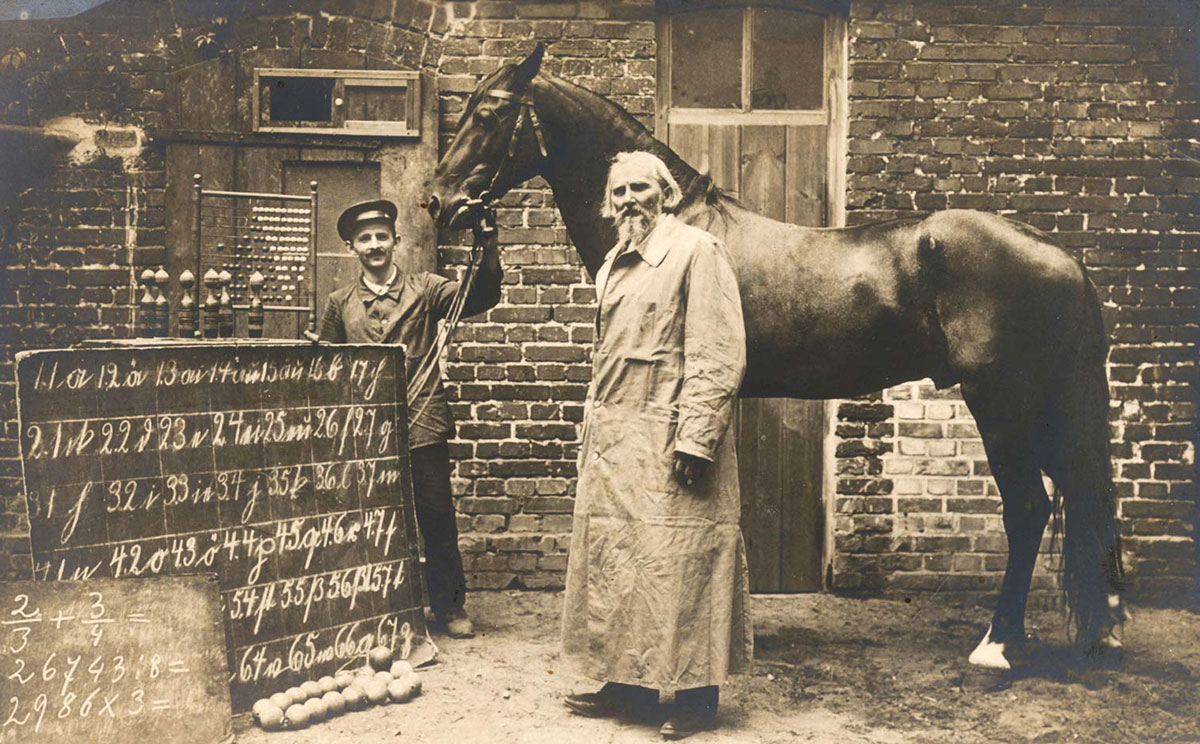

The Horsey History of Clever HansSkeptoid Podcast #633  by Brian Dunning You've almost certainly heard the story of Clever Hans, the horse who, in the early 1900s, amazed Europe with his apparent ability to count, perform mathematical calculations, and demonstrate other even more impressive feats of intellect. You've probably also heard that it was eventually discovered that these abilities were found to be nothing more than the horse reacting to unconscious cues given by the people testing him, a phenomenon that today we call the Clever Hans Effect. But you may not know just how deep was his impact upon the use of experimental controls and a variety of sciences including psychology and communication — even parapsychology. Today we're going to learn about the amazing life of this famous horse, and find out just how he came to be so influential, even more than a century later. To learn about Hans, we must first learn about his owner, Wilhelm von Osten, a retired Prussian schoolmaster in Berlin, Germany — crotchety, foul tempered, slouched and slovenly in appearance. He had bought a carriage horse in 1888 and named it Hans, and had grown impressed with the horse's ability to know its way around and apparently make conscious decisions. Von Osten trained Hans to drive without reins, responding only to commands; and also to stamp its hoof to indicate numbers up to five. Von Osten made public demonstrations of Hans' abilities beginning in 1891. By all accounts, von Osten was a sincere believer in horses' great intelligence, and appears to have been quite skilled at training them. He was not a hoaxer. Unfortunately Hans died at the age of 12, and von Osten sought a replacement. He found a beautiful black Orlov Trotter which he purchased from Russia in the year 1900, about five years old, and also named it Hans. This Hans was the one soon to be known to all of us as Clever Hans, but note that it's a different Hans than was featured in von Osten's earliest public demonstrations. Hans the Second initially seemed to follow in his predecessor's hoof prints, but von Osten was never able to summon interest from the scientific community in his horse. Finally, in 1902, von Osten took out an ad and tried to sell Hans:

It was this ad that launched the career of Clever Hans. Nobody offered to buy him, but some German military horse experts came to see a demonstration. The famous African explorer and naturalist C.G. Schilling also heard about it, and Hans even came to the attention of the Minister of Education. By 1904 a commission from the 6th International Congress of Zoologists in Berlin nominated Professor Carl Stumpf — director of the Psychological Institute at the University of Berlin — to conduct a scientific assessment of Hans' apparent abilities. Stumpf was assisted by his grad student Oskar Pfungst. Hans' talents were many. When an arithmetic question was asked, he stamped out the answer with his hoof. He identified musical notes played on a keyboard by tapping out a corresponding number. When asked to identify a color, he would tap out its number as displayed on a chart. As you've probably heard, Pfungst and the other scientists applied strict controls to see whether Hans was actually thinking abstractly on his own or was reacting to external stimuli. In a test merely seeing whether Hans could identify numbers, he was right 98% of the time when the number was known to the person showing it to him, but was right only 8% of the time when it was not — actually worse than random chance. In a test where he was to read a word written on a blackboard and stamp to indicate which was the matching word on a chart, he was right 100% of the time when the word was known to the questioner, but was wrong 100% of the time when it was not. Hans' most famous trick was to sum two numbers whispered independently to him by two different people. In the test, Hans was right 94% of the time when the questioner knew the answer, but only 10% of the time when he didn't — random chance exactly. Over many such trials, the evidence was clear that Hans could only perform any of his tricks when the face of the questioner was visible to him, and when the questioner knew the answer he was seeking. What was discovered is what we now call ideomotor cueing — the giving of prompts by unconscious, unintentional visual cues. The basic case in the example of Hans was that the questioner would slightly alter his facial expression, perhaps expressing pleasure or surprise, whenever Hans' stamping hoof reached the right number. Having exhaustively studied von Osten's teaching methods with Hans, Pfungst noted that von Osten would start Hans stamping by bending low and lifting his hoof; Hans would continue stamping, and as soon as the right number was reached, von Osten always slightly relaxed into a more comfortable position, whereupon Hans stopped. Hans' whole ability was based on many little cues like this, given innocently by well-meaning experimenters. Pfungst put blinders on Hans for some of the tests which restricted the direction in which he could see. One scientist wrote:

Pfungst even brought himself into the lab and learned to read numbers from people, tapping them out with his hand until he saw changes in their faces. Two out of 25 people he couldn't read at all; one of these was someone whom Hans also could not read. His 1911 book on the case, The Horse of Mr. von Osten, became the seminal work of ideomotor cueing, also known as The Clever Hans Effect. Today it has ramifications throughout cognitive psychology. What followed was to become the second chapter in Clever Han's life as a research subject — a chapter that's rarely told. Not everyone was persuaded by the scientific findings, including von Osten himself. Von Osten wrote that the reason Hans didn't perform when questioners didn't know the answer was that Hans detected their ignorance, lost respect for them, and then refused to participate correctly; it was a classic case of a true believer rationalizing away their failure to pass controlled testing. However, the well-publicized testing had brought Hans to the attention of Karl Krall, a wealthy jeweler by trade but also an amateur animal psychologist and occultist, who believed that Hans' abilities were psychic. Krall and von Osten became friends, and began what they called "silent speaking" experiments with Hans. Von Osten would think of a color or a number, then transmit it to Hans, who would then transmit it to Krall. Krall would do the same back, always with Hans as the intermediary. Upon von Osten's death in 1909, Krall took over ownership of Hans. Krall took Hans to Elberfeld along with a number of other horses, donkeys, ponies, and even an elephant, where he established a research laboratory. His 1912 book Thinking Animals described feats similar to what Hans could do being performed by several of his other "Elberfeld Horses", as they came to be known. Most notable among these were two Arabian stallions, Muhamed and Zarif. Krall improved von Osten's methods with an inclined platform that was easier to stamp on, and using one hoof to represent tens and the other for units. With these tools, Muhamed and Zarif solved great complicated algebra problems, cube roots, fourth roots; and even held lengthy conversations in several languages, tapping out letters to spell. Their abilities seemed to defy all skeptical explanation. However, what's known about the Elberfeld results is known mainly from Krall's own book; and only 13 of its 500 pages discuss the actual experiments, with no mention at all of any protocols or controls. So, at best, glowing reports of Krall's results that appear in many books and journals of the day must be taken with a grain of salt. The Swiss neurologist Édouard Claparède visited and was initially impressed by the horses, but returned for a second visit and repeated his tests with stricter controls, and this time found that the horses' abilities disappeared. In one public display intended to prove that the horses did not need to see a questioner's face, Krall would ask the horses a question over the telephone, being well out of sight, with his assistant standing before the horse and holding the receiver up for them to hear. At least one scientist in attendance noted that Krall's voice coming through the phone was perfectly audible for everyone nearby to hear, including the assistant standing right in front of the horse! Farcical, to say the least; especially when considering that this demonstration was specifically to address criticism that they lacked controls to prevent the horses from reading facial cues. Nevertheless, Clever Hans and the other Elberfeld Horses became a staple of the literature promoting the idea that animals possess psychic abilities. In other very different books, they remain a significant milestone in the history of the cognitive psychological sciences. When World War I broke out in 1914, Germany mobilized almost three quarters of a million horses for the war effort, a ratio of one horse for every three men. Clever Hans, ten years older than he had been in his days of fame, was one of these; his past notoriety held less value for the country than he himself did as a mount. After Hans was drafted into the military, the records of his life end, so we don't know what ultimately became of him. The vast majority of draft horses did not survive the war. A quarter of those who died fell to enemy action; the rest to disease, exhaustion, and untreatable injuries from falling in mud and shell holes. At the conclusion of hostilities, most of those that remained were quarantined due to their likely exposure to disease, and went to the slaughterhouses. By this time Hans would have been a senior horse, and the chances are that his extraordinary story came to an end somewhere along the battlefront. But of the approximately one million anonymous horses he died alongside, the name of Clever Hans is the one that will always be remembered — for all that he taught us about psychology, about experimental controls, and about ourselves.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |