|

|

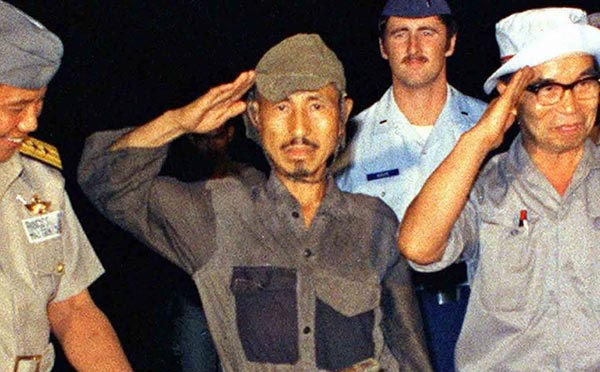

Relict Japanese SoldiersSkeptoid Podcast #585  by Brian Dunning Today we're going to toss the anchor overboard and row ashore to a beautiful South Seas island, and just as we're setting up camp, we hear a shout in Japanese. There, emerging from the jungle, is a World War II soldier, in full battle uniform, pointing his rifle menacingly. It's a scenario that has become popular in fiction: that of the relict Japanese soldier, marooned on an island for decades, who never got the word that the war had ended. Is this merely the fictional invention of imaginative authors, or is it fact? Might there have been Japanese belligerents still tucked away in remote corners of the Pacific all the way through to the end of the twentieth century? The Western stereotype of a relict Japanese soldier is actually pretty well represented by a 1965 episode of Gilligan's Island called "So Sorry, My Island Now". A Japanese soldier, who had been patrolling in his one-man submarine for 20 years, takes the castaways prisoner. He doesn't believe the war is over because his radio is broken and he never got the news. His portrayal is a grossly racist buck-toothed stereotype, based on the war-era propaganda drawings of Japanese. It is strongly reminiscent of Mickey Rooney's infamous performance of Mr. Yunioshi in the 1961 film Breakfast at Tiffany's. When we think of a relict Japanese soldier, we think of a lone, fully uniformed warrior who comes charging out of the jungle with his bayonet affixed, samurai sword at the ready, shouting angrily in Japanese. This lone uber-patriot is a good place to start deconstructing the stereotype of the relict Japanese soldier. In Japan, they are called the zanryū nipponhei, "remaining soldiers". Most Japanese historians estimate that about 10,000 zanryū nipponhei failed to return to Japan after World War II. There were good reasons why many did not want to return. A lot of them were justifiably concerned about prosecution by the occupying forces for war crimes. Many, while stationed throughout the Pacific and Asia, had married local women. Some were afraid of radiation from the atomic bombs that had been dropped in Japan, or had lost their families in those raids and did not want to return. Finally, there are two other reasons that are of the most interest today: Involvement with local independence movements, which is responsible for the largest number of desertions; and then failure to get word that the war had ended, which is really the subject of interest in this episode. First let's find out where the bulk of the Japanese deserters went. To do that, we have to understand what the Japanese military was doing after the surrender. They were still a large force, and there was still trouble brewing throughout the region, so the Allies put them to work. In Mainland China, a civil war had been simmering for decades between Mao Zedong's Soviet-backed Communists and Chiang Kai-shek's Western-backed Republicans. Japanese had been stationed throughout China during the war; and when it ended, thousands were faced with either being captured and sent to Soviet gulags, or being compelled to join the Republican forces. These came to be known as "ant soldiers", most in the Shanxi province. After four years of fighting, their side lost, and many of the survivors assimilated into Chinese culture. Indonesia, which had long been a Dutch colony, had been occupied by Japan during the war, and declared independence two days after the Japanese surrendered. Japan fought the rebels, but it was an extremely unpopular fight among the demoralized Japanese soldiers. Desertions were wholesale, which also transferred arms and equipment to the Indonesian rebels. When the Dutch and other Allied forces regrouped following the war in Europe and were able to come back to attempt to retake Indonesia, many Japanese fought on the Indonesian side. After the revolution ended, those Japanese who remained were treated with great honor and appreciation by the Indonesians. Vietnam had been wrested by the Japanese from joint control with the French during the war. Upon the surrender of Japan, Ho Chi Minh staged the August Revolution to seize power from the Nguyen dynasty. French and British troops responded, conscripting a large Japanese force to fight as well. But the Japanese were not motivated to fight to give Vietnam back to the French. So although they are officially listed as having fought on the Allied side, many deserted to the Vietnamese side and fought for Ho Chi Minh. As in China and Indonesia, most of those elected to remain in the country after the war, due to any combination of the reasons discussed earlier. So now onto this final group, the one with more of a pop-culture mythological element to it: the relict Japanese soldier, hiding out on a jungle island, believing the war to still be going on, even into the 1970s, 1980s, and possibly later. Is there any truth to this? The historical basis is sound. There were countless Japanese scattered throughout the islands of Indonesia, the Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Guam, and the rest of the region. Many had taken heavy poundings and were cut off, disorganized, and often lacking proper command and control. Many of these truly did not get the order to surrender, and of the majority who did, many took it to be an American trick and did not comply. In the first weeks and months after the surrender, there were many such cases of individuals and even whole companies who remained belligerent until being persuaded that the war had in fact ended, so it's impossible to draw any lines between who was a zanryū nipponhei and who wasn't. The most famous case concerned four soldiers on Lubang Island in the Philippines who formed a group after the Allied forces took the island in 1945, a conflict in which all the rest of their comrades were either killed or taken prisoner. They were without any command and control, and their ranking officer, Lt. Hiroo Onoda, was trained in sabotage and demolition. They made wisely infrequent attacks against Philippine soldiers and civilian police officers. Islanders made a number of efforts to communicate with them to advise them of the end of the war (including once writing them a letter affixed to a gift of a slaughtered cow), but they decided all such attempts were tricks. Even letters from family with photos begging them to come out, airdropped all over the island, were determined to be hoaxes. After four years, in 1949, one of the men gave up and surrendered to Philippine police. Another was killed in a shootout in 1954. In 1972, while the two surviving saboteurs were trying to destroy a crop of rice, the third was killed by police. Two years later, Lt. Onoda was the sole survivor, and he was met by Norio Suzuki, a young Japanese adventurer who had sought him out. Onoda agreed only to surrender to his superior officer. Suzuki returned to Japan and Onoda's former superior was actually located, still alive and then working in a bookstore. The two returned to the Philippines, and in a poignant and widely publicized event, Philippine authorities accepted Onoda's surrender in 1974. He was pardoned by President Ferdinand Marcos and allowed to return to Japan. Not all were so dramatic. Shoichi Yokoi was one of the survivors of the garrison on Guam, some of whom scattered into the jungle as guerilla fighters. Yokoi was one of those who never heard the surrender order. Ten of them elected to hide out. Three chose to live in the same area of jungle and kept in touch, but two were lost in a flood in 1964, leaving Yokoi alone. He lived in a dugout shelter braced with bamboo, and survived mainly on trapped river eels. He avoided all contact with Chamorros (people from Guam), but bumped into two hunters unexpectedly in 1972. He tried to fight them but was overpowered and taken into town. He was brought back to Japan as a hero and earned a good living as a public speaker. Yokoi kept a journal of his time on Guam, published in Japanese by his nephew. Only one other relict soldier is known to have lived in isolation later than did Onoda, and that was Teruo Nakamura. He fought on the island of Morotai in Indonesia, and essentially deserted into the jungle along with others after the island fell to the Allies. He lived simply in a secluded hut, meditating and subsistence farming. For decades he had contact with only one person, a villager named Baicoli. Later Baicoli also introduced his son Luther, and they agreed to keep Nakamura's secret. But once Baicoli died, Luther became concerned about Nakamura's failing health, and gave him up to the authorities for his own good. The other known zanryū nipponhei were men who had deserted to live peacefully in other countries, and there are many of these, even who returned to Japan during the intervening decades. Onoda and his group of saboteurs are really the only ones who fit the stereotype of the Gilligan's Island soldier. Their exploits had indeed created a bit of a folklore by the time the Gilligan's Island writers were looking for inspiration, but Onoda himself didn't surrender until seven years after the episode aired. Given that timeline, we find we have a bit of a minor mystery. What inspired the Gilligan's Island writers, could it have been nothing more than the local legend of Onoda? Turns out it was a little bit more. There was one character most influential in creating the legend, even though his own story bears little resemblance to the proverbial relict soldier. Sakae Ōba, called the "Fox of Saipan" by the Americans, was an officer who led 46 soldiers and 200 Japanese civilians into hiding after Saipan fell to the Allies, a year before the end of the war. They successfully evaded capture until three months after the surrender, often conducting successful strikes against the American positions, all the while seeing to the needs of their civilians. Only when presented with official surrender documents by a Japanese Major General did Ōba hand his sword over to an American Lt. Colonel. Many years later, an American soldier who had fought against Ōba successfully brokered the return of this sword to the Ōba family. It was the story of Sakae Ōba that turned the idea of the fiercely patriotic relict Japanese soldier into the kind of urban legend that inspired Western fiction, even though his own campaign lasted a mere three months beyond the surrender. In August 2014, Japanese news services reported that Sakari Ono had died in Indonesia, aged 95. After the surrender in 1945, Ono was one of the deserters who assimilated into Indonesian culture. He fought in the Indonesian National Revolution and remained in the country until his death. So far as has been reliably reported, that I could find, Ono is believed to have been the last of the zanryū nipponhei.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |