|

|

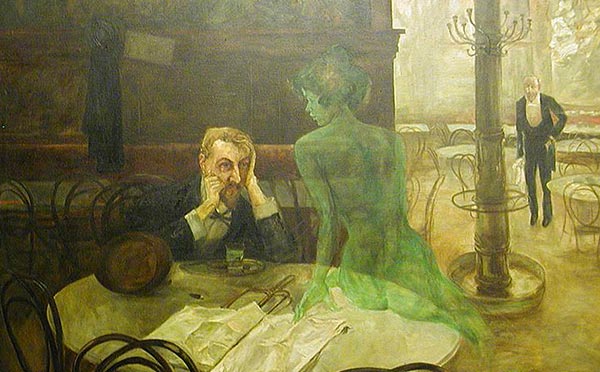

All About AbsintheThis mysterious alcoholic drink is the subject of more urban legends than any other liquor. Skeptoid Podcast #515  by Brian Dunning They call it the Green Fairy, this mysterious licorice-flavored alcoholic drink, subject of more urban legends and mythology than all other liquor types combined. Some say it induces insanity or hallucinations. Some go farther and claim it cause epileptic convulsions and even death. A host of famous artists and writers have used it to enhance their creativity, with evident results; so could it be that some of the myths about this maligned beverage — which has been banned in many countries — have a grain of truth? Absinthe was first developed in Switzerland as a patent remedy, but is most famous for its popularity in Paris where it quickly went from snake-oil cure-all to recreational beverage around 1800. Its popularity grew until the late 1800s when there began to be something of a backlash against it. The health fears began rising, and it became associated with lower social classes, and began to be viewed more like a stigmatized drug than a drink for the people. There arose a belief in a medical condition called absinthism which combined convulsions, tremors, and hallucinations. A famous 1876 painting by the Impressionist artist Degas titled L'Absinthe shows a morose woman, isolated from society, sitting in a drab cafe having a morning glass of absinthe as a hangover cure — and though many who see the painting miss it, Degas hid a hallucination in plain view: the tabletops are floating in mid-air with no legs to hold them up. The painting was considered immoral and was hidden away for a time. Wine and beer were what Parisians considered "hygienic beverages", but absinthe — widely regarded to be addictive and hallucinogenic — was most certainly a breed apart. High profile writers and artists often publicly proclaimed their affinity for absinthe, and many credited it with boosting their creativity. Ernest Hemingway, Vincent Van Gogh, and Oscar Wilde were just a few. Around 1915, anti-absinthe sentiment and the growing temperance movement converged and the drink was banned in many western countries. The vilified ingredient was thujone, a compound that comes from one of absinthe's main ingredients, the grande wormwood. Some urban legends have claimed thujone is similar to THC, but it's not. In fact it has no effect at all at concentrations that could ever be obtained by drinking absinthe. Only in far, far higher amounts can thujone do anything to you, and then its effects are muscle spasms and convulsions, not hallucinations. The United States lifted its ban in 2007, but like most countries that did so, strictly regulated the amount of thujone. In most countries the amount of thujone in absinthe is limited to somewhere around 10 to 35 parts per million. There is no science-based reason for this; the limits are purely bureaucratic. There are oddball rumors that absinthe contained heroin or marijuana other psychoactive drugs, but no evidence has ever surfaced indicating that such a product was ever produced. In fact, lots of people have done gas chromatograph and mass spectrometer analyses comparing modern absinthe with 19th century absinthe (which can still be found), so we do know for a certainty that whatever ingredients used to go into it are the same ones that we put into it today. So to better understand what these mysterious ingredients might be, let's take a quick look at how it's made. We start with alcohol, purchased or acquired from some source. Traditionally, absinthe uses alcohol made from distilling white grapes. Lesser absinthes may use grain alcohol, or alcohol distilled from beets or potatoes. It doesn't really matter. It's put into copper stills along with the principal ingredients: shredded grande wormwood, green anise, and florence fennel. This soaks overnight, a process called maceration. Then steam is pumped into the stills and the absinthe comes out a valve at the top. The first stuff that comes out is way too alcoholic and oily and is discarded, and the last stuff is really weak and is also discarded. But the main part of it is finished white absinthe, with an alcohol content of 78-80%. To make green absinthe, this mixture is then added to another still and steeped in another batch of ingredients in burlap sacks: petite wormwood, hyssop, mint, chamomile, or other herbs according to the individual distillery's recipe. This is where the chlorophyll enters the mix, giving green absinthe its color. Green absinthe is always bottled in dark glass to protect it from the light, which causes it to turn yellow. Very cheap absinthe can be faked by simply soaking the ingredients in alcohol, then adding enough water to dilute it to the desired alcohol content. When finished, most absinthe has an alcohol content of 60-62%; significantly more than most liquors. That's why it's rarely consumed straight. Rather, absinthe is intended to be diluted, with an elaborate traditional method for which it is well known. Enthusiasts will use a special absinthe glass with a bulge at the bottom. You fill the bulged portion with absinthe, then you lay a slotted absinthe spoon across the top of the glass. You place one or more sugar cubes on the spoon, and place this assembly under an absinthe fountain — basically a big carafe with spigots for two or more glasses — which drips ice cold water onto the sugar cube. As the water hits the absinthe, it undergoes what they call the louche, which is a reaction where the absinthe clouds up. By the time the glass is full, the sugar is dissolved, and you have a nice glass of thoroughly cloudy, sweetened, and diluted green happiness. It should be noted that none of the above is necessary; it's purely traditional. Absinthe can also be consumed straight. Adding water or simple syrup produces exactly the same results as the fancy procedure just described. Purists will argue vehemently, but they might as well be arguing vinyl vs digital. There's no difference. Some modern servers will also jazz up the ceremony by lighting alcohol-soaked sugar cubes on fire and dropping them into the high-alcohol mixture. Parisians never did this back in the day, it's strictly a modern invention. But if you want to do this, knock yourself out. It adds to the fun, but not to the drink itself. The turning of popular opinion against absinthe for health reasons was largely the fruit of one man's labor, French psychiatrist Valentin Magnan. He was something of a crusader against alcohol, believing that it was causing a decline in French culture. He was among the first to suggest that absinthe produced effects which exceeded those of other alcoholic drinks, and he focused on the wormwood as the probable cause. He took an essential oil of wormwood — which is, of course, far more concentrated than the plant as used in the preparation of absinthe — and gave it to animals, triggering the seizure effects that we now know to be caused by high exposure to thujone. The dose Magnan gave to the animals was astronomically higher than one could ever get by drinking absinthe; a Parisian would have to die from alcohol poisoning many times over before the first effects of thujone could possibly ever be felt. But it was a great sound bite. Absinthism was born; the scientific data (though deeply flawed) was established that would form the basis for the absinthe bans; and thujone was inappropriately branded as a dangerous ingredient throughout the 20th century. Even today, distilleries have to carefully manage the amount of wormwood going into each batch to match the destination country's maximum allowable thujone content, a precaution which is unnecessary by any stretch of the dose-response curve. What really cemented the fated ban was the Lanfray murders of 1905 in Switzerland. Jean Lanfray, who was said to have consumed two glasses of absinthe, shot his wife and two daughters dead, and failed at the attempt to kill himself. Within days, 82,000 Swiss signed a petition to have absinthe banned, and they were joined by physicians from all over the country citing Magnan's work. At his trial, Lanfray was said to have killed while in an absinthe-induced delirium, and the legislature voted 126-44 to ban absinthe. It is less often reported that Lanfray habitually drank five liters of wine each day; and on the day of the murders, had started with two absinthes before breakfast, followed them up with a creme de menthe and a cognac in a cafe, two or three glasses of homemade red wine with lunch, two more glasses during his afternoon break, a third with a neighbor, a coffee and brandy in another cafe, then a full liter of red wine at home. He finished his day's libations with a coffee and brandy just before the murders. Yet it was his two morning absinthes that were blamed. It turns out that the most interesting thing about absinthe is its louching, the way it clouds up when you add water. This effect is not unique to absinthe; it also happens most notably to ouzo, but also to any other liquor containing a hydrophobic essential oil dissolved in ethanol. In this case, that oil is anethole, which comes from the anise. Chemists call this louching the ouzo effect. The reason it turns cloudy is that the presence of water causes those hydrophobic oils to emulsify, which is where they coalesce into droplets about 1 micron in size. This causes light passing through to scatter, making the liquid appear cloudy. By itself, emulsification is not especially interesting or unusual. The ouzo effect is different in that the emulsification happens spontaneously, requiring no agitation or mixing other than what happens naturally just by dribbling in the water. It also forms an emulsion that is surprisingly stable; it will stay cloudy for months. Awesomely, this spontaneous emulsification is not fully understood, and potentially has significant industrial applications. It's not known who first uttered the author's credo "Write drunk, edit sober," but it's a maxim that has served many writers well over the centuries. Of his own obsession with writing while on absinthe, the poet Oscar Wilde famously said "The first stage is like ordinary drinking, the second when you begin to see monstrous and cruel things, but if you can persevere you will enter in upon the third stage where you see things that you want to see, wonderful curious things." Now that the absinthism hysteria is consigned to the history books, feel free to check into a cafe and see what wonderful and curious things the green fairy will reveal to you. I probably won't join you, because I personally think it's disgusting, but your mileage may vary.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |