|

|

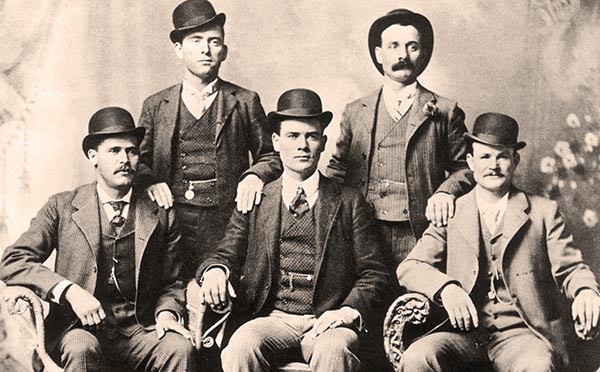

Finding Butch and SundanceSkeptoid Podcast #394  by Brian Dunning It was the most popular movie of 1969, winning an Academy Award for its screenplay by William Goldman. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid told a fictionalized version of the final years of the lives of the two infamous western outlaws, who are popularly (but not universally) believed to have died in a shootout in South America. Finally cornered in a small room in San Vicente, Bolivia, the movie versions of Butch and Sundance faced an entire regiment of Bolivian soldiers. Goldman's screenplay describes their fanciful ending best, though slightly different from what ended up onscreen:

However Butch and Sundance actually came to their end was probably less dramatic than this, but probably no less violent. We say "probably" because 100% firm evidence that the pair died on November 6, 1908, in San Vicente, Bolivia, does not exist. In fact, whole mountains of stories do exist that one or the other, or even both, survived the shootout and even returned to the United States. The Pinkerton Detective Agency, which had been pursuing the two for years, never did close their case, being unconvinced that the reports of their death were sufficiently reliable. Butch and Sundance — whose real names were Robert Parker and Harry Longabaugh — had felt too much heat following all their train robberies in the United States, and after several failed attempts to win amnesty, they fled to South America in 1901 with Sundance's girlfriend Ethel Place. Together the three lived on a ranch they bought in Patagonia. Over a span of seven years they kept their hand in the game, robbing banks and mine payrolls from Chile to Bolivia. Sometimes they were joined by one or more of their former partners from their "Wild Bunch" that had become so notorious in the western United States. Butch used to write letters home to family, and much of what we know of their exploits comes from this documentary evidence. There certainly were other bandits throughout South America, so the history begins to get a bit fuzzy and, to this day, we're still not certain whether a number of robberies were done by Butch and Sundance, or by others. So to find out if Butch and Sundance may have survived, we first have to discover why we think they died. And to do that, we have to go high into the Bolivian Andes. Really high, in fact; well above the treeline, where there's nothing but dry brown sand and rock. At 4500m (15,000 ft), the air is thin, and it's cold and dry all year. The Andean High Plateau stretches for hundreds of kilometers and is exceedingly remote. Beginning in 1820, hardy Bolivian miners found silver veins there, and San Vicente was born. But even nearly a century later, its brutal conditions and nearly inaccessible location had kept San Vicente only a tiny mining camp with a few dozen adobe buildings, well clear of any governmental authority or proper services. Far away, on November 4, 1908, trouble was brewing. Two white men tracked three couriers from the Aramayo mining company, the richest one around, and after a day, they robbed them of 15,000 pesos worth about USD$100,000 today. Trekking home, they stopped to spend a night at San Vicente, but found there were no accommodations for visitors. The camp administrator, Cleto Bellót, put them up in an abode hut adjoining one miner's house. They had some small talk about who they were and where they were going; they gave their names as Brown and Maxwell, and they were heading north. The miner provided them a dinner of canned sardines and beer. Unfortunately for the happily munching outlaws, two hours before, Bellót had also just put up (in another of the town's huts), a posse of four men who were searching for two "yanqui" bandits with a mule bearing the Aramayo brand. So after making sure the newcomers were comfortable, Bellót excused himself, went down the block, and roused the posse. Three of them — two soldiers and a policeman — accompanied Bellót back to the house, guns drawn. The sun had just set and lamps were being lit throughout the town. It was bitterly cold. The clumsy posse stepped into the light from the house's open door just as Maxwell (the smaller of the two men) happened to appear in the doorway. Maxwell immediately drew his gun and shot dead the lead soldier. Everyone scattered for cover and began firing. Soon guns were emptied, and the soldier ran back for more ammunition. The officer roused anyone else he could find to help cover the back of the house to see they didn't escape. What's often described as an action-packed gunfight was really just the posse firing blindly into house, in the twilight, with Brown and Maxwell occasionally firing back. At one point, screams of pain were heard from inside. As the darkness became complete, the guns became silent. The posse watched the house all night. At first light, the posse crept inside, guns at the ready, to find the fight had ended the night before. Brown and Maxwell both lay dead, each wounded in the arm. In addition, from their positions in the room, it was clear that Maxwell had shot Brown in the forehead, from inside the room, and then himself in the temple. The first soldier killed by Maxwell was the only other casualty. The two men were positively identified by the victims of their robbery and by others, and the money from the Aramayo mine was found in their saddlebags. Yet in the lack of any proof of identification, they were buried as "Unknown" in San Vicente's cemetery. So what have Brown and Maxwell got to do with Butch and Sundance? Brown (sometimes Boyd) and Maxwell were the aliases the pair had used when working, and over the span of many years living in South America, they'd accumulated a large circle of friends including many other American expatriates, such as Frank Aller, the American vice-consul in Chile. Word quickly spread that Butch and Sundance had been killed, and nothing further was ever heard from either man. Percy Seibert, who had been their manager when they worked at a Bolivian mine, had grown close with them and said their true identities as Butch and Sundance was something of an open secret. It's the kind of evidence that can't be considered proof, but that would probably sway a court of law. Perhaps most significantly, Aller wrote to his counterpart in Bolivia asking for Brown's death certificate, saying they were needed by a Chilean judge to settle Brown's estate. The reason for this is not known. Some have suggested that Ethel asked him to do it, but there's no evidence for this. Aller had bailed Sundance out of jail previously, and had often helped him in other various run-ins with Chilean authorities. It's not by testable evidence, but rather by a preponderance of testimony and circumstantial evidence that we say with practical certainty that Butch and Sundance were the men killed in San Vicente. And yet stories abound that both men — though the majority of the stories only include Butch — either weren't there or survived the siege, and returned to the States and lived a long happy life. The most noteworthy claim was made by Butch's sister Lula, who said that he visited the family in 1925. But the rest of the family denied it. Lots of letters have appeared over the years allegedly attributed to Butch Cassidy, all written after San Vicente. But so far, those that have been conclusively identified by forensic handwriting analysis have all been proven fakes. Even The History Channel — the world's greatest promoter of sensationalized false history — presented an alternate view in a documentary called History vs. Hollywood in which they claimed that letters written by Butch Cassidy continued after the San Vicente shootout. Whenever we have a story that involves a body and a grave, it's always tempting to ask why not simply go and dig it up and do DNA testing. San Vicente's little cemetery is in the same place now as it was then, so in 1991, a television crew for the series NOVA went down there to check it out. They brought along forensic anthropologist Clyde Snow, famous for doing all sorts of groundbreaking work throughout the world, including Kennedy, Tutankhamun, and Mengele. The crew did their best to exhume skeletons only from where research had shown Brown and Maxwell most likely lay. Armed with genetic material from a surviving relative of Sundance's, the team analyzed the one candidate skeleton who was a potential match for the outlaws. The skeleton was definitely not related to Sundance. Of course, the team appropriately did not tear up the entire cemetery. "We may have been off 5 feet, or maybe 3 feet," Snow said. "Maybe if we could've gone a little further, we would've run into Butch or Sundance." Today, San Vicente is still a tiny, single-employer mining town, a few rows of prefabricated buildings rattling in the thin, dry breeze. It's a lonely and quiet place, which could almost pass for abandoned. There is the walled cemetery, yet another part of San Vicente that has been unchanged all these years. And in that cemetery, you'll find graves from every era, scattered and intermixed, many bearing a splash of color from artificial flowers that can stand the extreme altitude and arid conditions. One marker, a whitewashed block of stone, is surrounded by metal stakes, their white paint flaking, loosely linked with an aging and rusting cable: AQUÍ YACEN LOS RESTOS DE BUTCH CASSIDY Here lie the remains of Butch Cassidy. But they don't, really. All that's under there is dust and history. Almost certainly, Butch and Sundance were buried somewhere within those stone walls, and probably some of that dust is theirs. Like the history from whence they came, they've melted back into the realm of legend and dry wind, all but forgotten by the miners of San Vicente who still toil at the same mountain.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |