|

|

Student Questions: Airport X-Rays, Shampoo, and the MoonSkeptoid answers another round of science questions sent in by students all around the world. Skeptoid Podcast #249  by Brian Dunning Put on your thinking caps, because today Skeptoid tackles another round of student questions. I invite students of all ages from all around the world to send in their science questions, and I'll point the skeptical eye at them. Today's questions cover the safety of the new X-ray machines being installed in airports; whether shampoo actually does the things it says it does (besides just washing your hair); the safety of non-stick cookware; whether it's more environmentally friendly to use washable diapers rather than disposable; and what effects the moon truly has on Earth, given all the many myths about it. Let's get started with the X-ray machines:

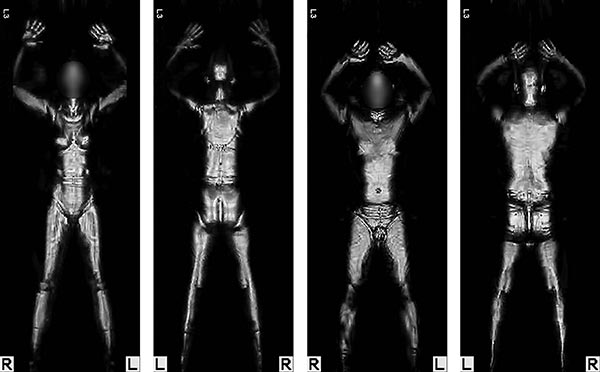

Few people have an adequate understanding of what these machines actually do. The technology you're referring to is backscatter X-ray. Unlike a medical X-ray, which shines X-rays through your body to produce a shadow image on a photographic plate, backscatter X-ray uses far lower intensity that cannot penetrate your body. Instead, it reads the X-rays reflected back off of the person, or "backscattered". The concern is because X-rays are ionizing radiation. Ionizing radiation is that which is at a high enough energy level that it can strip electrons and change chemistry, which is one potential cause of cancer. The dosage of radiation from X-rays is measured in microsieverts. To put a medical X-ray into perspective with an airport backscatter X-ray, a chest X-ray delivers 100 microsieverts; an airport scan delivers .02 microsieverts. You'd have to get scanned 5,000 times to equal the radiation dosage from a single chest X-ray. 10 microsieverts, or about 500 airport scans, is considered a negligible risk. Why negligible? Just existing on the Earth, we're all being exposed to ionizing radiation constantly. You're being hit by cosmic gamma rays right now, and other natural sources, to the tune of some 3,000 microsieverts per year, equivalent to some 150,000 airport scans. Flying in an airplane, you have less atmosphere to protect you, so you're exposed to more; about 20 microsieverts on a coast-to-coast flight. One backscatter X-ray airport scan gives you the same radiation you'd receive by flying in the airplane for four minutes. It is so small it's not even worth counting. But if 1/500th of negligible is still too much for you, try the competing airport scan technology: Millimeter wave scanning. These use radio waves. Radio waves are not ionizing radiation, so they pose no plausible threat to health at all.

This is a great question, because I love calling out deceptive marketing claims. There are some things hair products can do, and some things they can't do. The most important point to understand is that hair is not living tissue. It has no circulatory system and cannot metabolize anything. Some products claim to deliver vitamins or other nutrients to your hair. This is not possible. Hair does reflect what we eat and what we have in our system, so if you want to get vitamins and nutrients into your hair, you have to eat them and wait for new hair to grow. Existing hair cannot metabolize or otherwise absorb nutrients; its makeup comes from your circulatory system, not from anything you put on it topically. But compounds can be applied to the surface of hair. Think of polishing a table or waxing a car. This is what conditioners do to your hair; they add a layer of some coating. Hair strands can split or fray or become otherwise damaged; silicone polymers from conditioner can fill in those gaps and sort of glue it back together, making it appear smooth or shiny. In short, the active ingredients in shampoos are detergents for washing stuff off; and the active ingredients in conditioners are polymers that add a coating back on. They basically do what they say, so long as they don't say they do anything more than that.

This has been a growing question of concern for some time. Almost all non-stick cookware is coated with Teflon, and Teflon does contain potentially hazardous chemicals. Good Housekeeping magazine decided to settle the debate, and they tested a number of different pots and pans, and spoke with the manufacturers and with independent experts. What they found is about what you'd expect. Like most products, it's completely safe if used as intended. The main concern is with temperatures that are too high. Above 260°C/500°F, Teflon starts to break down and releases fluoropolymers. These include fluorine containing compounds, which can be toxic. Thus, it's always recommended to keep temperatures as low as necessary, both to minimize the release of fluoropolymers and to preserve the life of the cookware. Of lesser concern is chipping, where damaged pieces of the Teflon may come off into the food and be consumed. In their bound state they're essentially inert, and will pass right through your system without being absorbed. Like all compounds, including water, air, and puppy dogs, whether the chemicals in Teflon are poisonous or not depends entirely upon the dose. It's virtually impossible that you could ever get a harmful dose of Teflon even as it's breaking down from too-high temperatures. You'd have to eat so much overcooked beef stroganoff that you'd die from that first. Keep the temperatures where they should be, replace pots that start to chip or get damaged, and you've got nothing to worry about.

This is an age-old question that continues to be hotly debated in both the diaper industry and among parents choosing opposing options. The average baby uses about seven thousand diapers before toilet training, and about ten percent of parents use cloth diapers, either exclusively or to some degree. Many of the debates you'll read go into excruciating detail, considering the energy consumed in building manufacturing plants, to the fuel comparisons between laundry trucks and manufacturing trucks, etc. etc. etc. However, all these are minor considerations. It turns out, at the end of the day, that the only truly significant environment impacts of each are landfill space for disposables, and water for laundering cloth. Which effect is worse for the environment depends entirely upon whose research you read. Read any study funded by the companies who make disposables, and you'll learn that they're best. Read any study funded by the companies making washables, and you'll learn that they're best. Read any study that tries to take an objective, unbiased view, and you'll find that the research is unclear, comparing landfill space to water usage is an apples-to-oranges comparison, and that any benefit upon the environment conferred by either product is likely to be pretty insignificant. Some point to a new generation of allegedly biodegradable disposables, and biodegradable liners for cloth. These don't have much effect on the equation. An industry for composting such products has never successfully materialized, so they end up in a landfill. And nothing degrades in a landfill without light and air, biodegradable diapers included. When researching this, keep in mind that the majority of published information is biased one way or the other. Do a thorough survey of both sides, and you'll probably come to the same conclusion I did: Use whichever you prefer, and understand that any claims to significant environmental superiority by either side are probably exaggerated. There's just not that big a difference.

The moon does not have "many" effects on Earth; it really has just two: Gravity and reflected light. The gravitational effects of the moon are most famously responsible for our tides, and even though this has a dramatic observable result as we can watch the water go up and down, notice that the effect is so small that we can't detect it ourselves, at least not without very sensitive instruments. We can stand on a scale at high tide and low tide and read the same weight. It's a very, very small effect, far below the thresshold of living creatures to detect. It's only large cumulatively over the entire planet. There are actually five different answers to the question of "How long does it take the moon to orbit the Earth," based on "Relative to what?" We have a draconic month of 27.2 days, ranging up to a synodic month of 29.5 days. However, the moon passes overhead every 24 hours and 50 1/2 minutes, so this is what governs the tide cycle. It's also what would be read by any biological system that is sensitive to tide cycles. Aquatic animals, for example, that respond cyclically are more likely in sync with the tides, with no need to directly detect the imperceptible gravity changes. As far as plants and wood are concerned, what cycles they have are in sync with the seasons and with daylight. These are the natural cycles that affect plant growth. I'm unaware of any evidence that cut wood could possibly be any different based on the moon phase; there's no facet of plant metabolism (that I know of) that uses this cycle. If there were, it would likely be problematic for the plant, as this cycle is not in phase either with the seasons or with daylight, and would thus disrupt the metabolic system. Students, keep those questions coming in. Just visit Skeptoid.com and click on Student Questions.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |