|

|

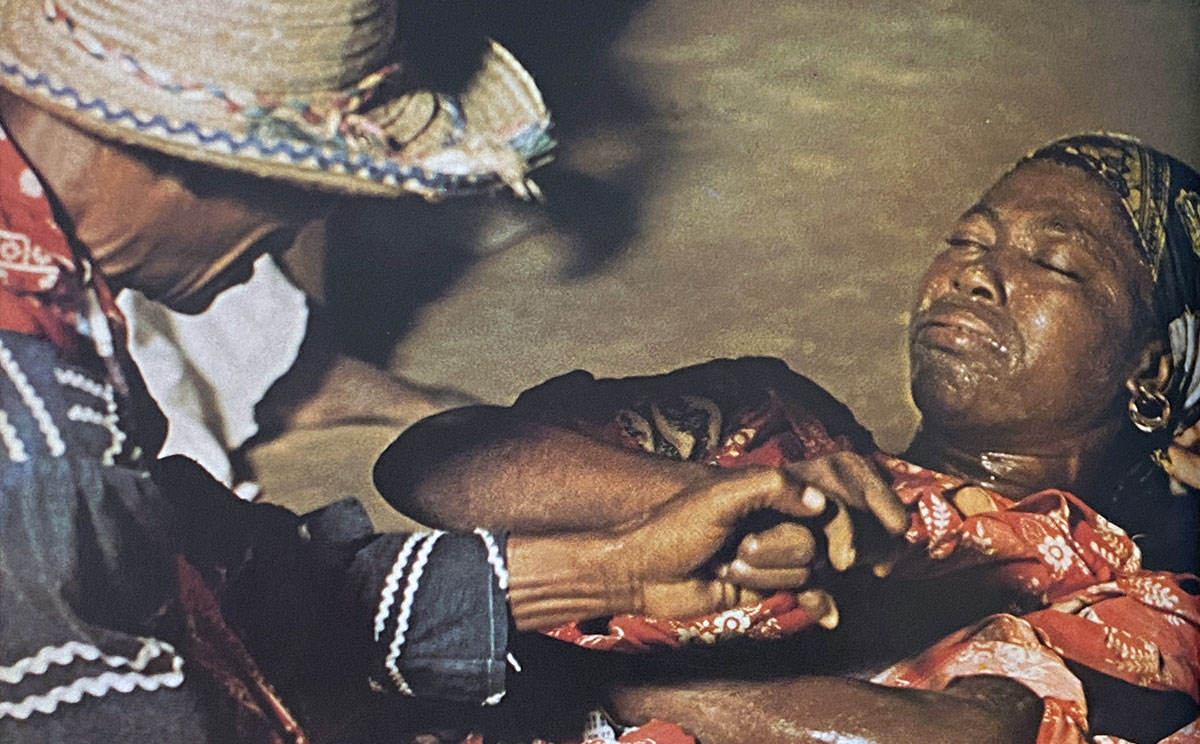

The Haitian ZombiesA look at the possibility that legends of Haitian zombies may have a grain of truth. Skeptoid Podcast #262  by Brian Dunning Should you find yourself in Haiti, beware of the man they call the bokor. Vodou tradition warns that he may secretly sprinkle a powder onto you, causing you to fall ill and quickly die — apparently. Doctors can examine you and find no pulse, no respiration. You'll be buried and your friends and family will attend the funeral. Then, one night, the bokor will come and exhume your body, and administer a mysterious antidote. Your body will wake up, but your consciousness and personality will be gone. Your body will be a dumb slave, eating, breathing, working, following the bokor's commands, perhaps even sold into labor; until it grows old, the joints fail, and not even the bokor's magic can keep it going. The remainder of your life will be as a zombie. To study the phenomenon of zombies, we have to answer a number of questions. We want to know if the Vodou tradition actually does include zombies, or if it's merely a dramatized caricature invented by storytellers to frighten Western audiences. We want to know if this has ever actually happened to anyone, the way it's described. Finally, if these answers are all yes, we want to find out if there is a pharmacologically plausible explanation for what's said to take place. The first question is easily answered. Vodou tradition does include zombies, and belief in zombies is nearly universal among Haitians. 50% of the population self-identify as Vodou, and most of the rest call it Catholicism, though it's really a syncretism of the Afro-diasporic roots along with what the French missionaries taught. It's polytheistic and includes both white magic and black magic, and its ceremonies often involve drug-induced trances believed to be possession by gods. Bokors (Vodou sorcerers) openly practice zombification, and though few Haitians have ever met a zombie, even fewer doubt that it happens. The second question, whether zombification has ever actually taken place, is the most important, and one that's all too often taken for granted in such mysteries. Before trying to explain a strange event, first establish that the strange event ever actually happened. If there's one thing I've learned from Skeptoid, it's that that answer is no more often than you'd think. Are there actually any reliably documented cases of people being raised from the grave and living out their lives as mindless slaves? The most familiar case is that of the man who is the subject of Wade Davis' 1985 book The Serpent and the Rainbow, the Haitian man Clairvius Narcisse. In 1962, Narcisse was about 40 years old when he checked himself into the hospital complaining of pain and difficulty in breathing. Two days later he was dead, and his official death certificate is on file. His body lay in the morgue for 24 hours (in unsurvivable refrigeration) until his family collected his body and buried him in the family plot. 18 years later, Narcisse suddenly identified himself to his sister in the street and told a shocking tale. He'd been conscious but unable to move or breathe during his entire stay in the hospital and subsequent burial. After three days underground, his coffin was suddenly opened. He was beaten, gagged, forced to take a hallucinogenic drug, and dragged away to face two years of slave labor on a sugar plantation, as one of many similarly imprisoned zombies. He reported being in a dream state with no willpower the whole time. Finally another zombie killed a captor with a hoe, and the zombies all escaped. Narcisse wandered for sixteen years, afraid to return home, convinced that his brother had been behind the plot. Then, upon his brother's death, he visited his sister. Narcisse has maintained his story, and even appeared in the 2008 documentary film When the Dead Walk. When Narcisse's story broke in 1982, Dr. Lamarque Douyon, director of Haiti's only modern psychiatric facility, wanted to know if the man was genuine. DNA fingerprinting was not yet available, so he questioned Narcisse, his family, family friends, and neighbors, and established to his satisfaction that today's Clairvius Narcisse was indeed the same person who was born and grew up with that name. It seemed to him that whatever zombification drug Narcisse had been given, if that was indeed the explanation, would be an important discovery. So he consulted with an associate in the United States, Dr. Nathan Kline, who sent the bright young Harvard graduate student Wade Davis to find it and investigate. An ethnobotanist by trade, Davis was convinced that he'd found a satisfactory pharmacological explanation for what happened: the poison tetrodotoxin. He purchased samples of zombie powder from several bokors across Haiti, and though their preparations differed, he found three common ingredients: charred and crushed human bones, various plants with stinging spines, and pufferfish. Pufferfish is famous for being the source of the expensive and risky sushi fugu, which if not properly prepared, can administer a lethal dose of the neurotoxin tetrodotoxin. It comes from a bacteria that grows within pufferfish, newts, toads, and a number of other animals. Although they've built up resistance, for humans and predators it's deadly. Tetrodotoxin blocks a sodium channel in nerve cell membranes, preventing the nerves from being able to fire any muscles. In sufficient doses, which for humans is very small, it stops all muscle activity, including not only the voluntary muscles, but also the heart and muscles that control breathing. The victim is conscious but as there is no pulse or respiration, he loses consciousness and dies within minutes from the lack of blood flow to the brain. There is no antidote or treatment. However the effect is temporary, and a few fugu diners have recovered after their apparent death, having received just barely enough dosage to wear off before the brain was lethally damaged. Davis asked about Narcisse's report of having been beaten and drugged when he was exhumed. The bokors said that zombies are force fed a paste made of sweet potatoes, cane syrup, and a plant called Datura. Along with nightshade and henbane, datura has long been used in many cultures as a hallucinogenic drug. It contains scopolamine, hyoscyamine, and atropine. But as a recreational drug, it's quite dangerous, and would need to be administered by someone experienced in its use, such as a bokor. And so Davis published his book with this thesis: that tetrodotoxin produces a state indistinguishable from death, but that bokors have some way of resuscitating the victims, who have suffered sufficient brain damage from hypoxia that they live out their lives virtually as vegetables. But it received much scientific criticism, which focused on the zombie powder. Authors Takeshi Yasumoto and C.Y. Kao wrote in the British journal Toxicon that although pufferfish was indeed in Davis' powder, only insignificant amounts of tetrodotoxin were; and since tetrodotoxin breaks down quickly in water or in alkaline environments, it was implausible for it to be delivered as a poison in powdered form. However, the bokor preparations were all inconsistent with one another; some might have been stronger. In 1984, Dr. John Hartung at Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn fed Davis' zombie powder to rats, rubbed it on their skin, and even injected it into their abdomens, and observed no effect. From assessing the criticism and responses, my analysis is that a very few zombie powders are likely to deliver a dose of tetrodotoxin, and most are not. If bokors do indeed attempt to poison victims with their powders, the vast majority of such attacks will fail. Either an insufficient dose will be delivered, or the victim will die. Only once in a blue moon is it likely for a zombification to result in both a lucky knockout and a resuscitation, and the level of brain damage will be correspondingly variable. It's plausible, but unlikely; and if it happens at all, successes are probably extremely rare. Skeptical criticism of Davis also pointed out that the entire case of Clairvius Narcisse is based on a flawed presumption. Even with all the documentation and evidence, and all the research done by Dr. Douyon, there is no reason to identify Narcisse as the man who died and was buried. Haiti is not known for its wealth. In 1962, a hospital stay was beyond the means of many residents. The hospital where Narcisse is alleged to have died, the Albert Schweitzer Medical Center, charged $5 a day for local residents, and a higher rate for non-locals. But poor non-locals got sick too, and it was not unheard of for them to check in under the name of a local to qualify for the lower rate. We have no evidence to rule out the likelihood that some unknown man developed a fatal kidney failure (which is what the lab tests showed as the cause of death), checked in using Clairvius Narcisse's name, and subsequently died. It turns out that there is a perfectly plausible reason that the real Narcisse might have been just fine with this. In his younger days, he had been something of the family black sheep. He had a number of illegitimate children whose mothers demanded support, and some other bad debts, and was not well respected. In fact, during Dr. Douyon's interviews, he learned that the family considered Narcisse's sins to be the reason that the bokors had punished him with zombification. It all made sense to them. And, for a man with Narcisse's skeletons in the closet, seeking a change of scenery is hardly unheard of. Perhaps in his later years he had a change of heart and wanted to reconnect with his family. Considering the convenient circumstances, his zombification was a perfect cover story. Obviously this theory is unproven, but consider the alternative: He survived two days, conscious but with no heart or lung function and no oxygen to the brain, 24 hours of which were spent in hypothermic refrigeration in the morgue. He then spent three more days underground, and all of this with failed kidneys that lab tests showed were fatal; then emerged in perfect health and managed hard labor at the sugar plantation for years. Is all of that more plausible than a deadbeat dad simply skipping town? We could go on all day and examine the many stories like that of Narcisse, but the rest lack his documentation and are anecdotal at best, despite their abundance. Vodou practitioners drug themselves regularly and perform zombie rituals, and some probably go for extended periods under the influence of datura. Almost certainly, in Haiti's history, some have been poisoned by tetrodotoxin in zombie powder and survived, though any with sufficient brain damage to be called "zombies" had questionable utility as laborers and certainly would never have recovered. The grain of truth in the zombie mythology is a real one, but its popular portrayal — even within Haiti — is an exaggeration based on tradition and superstition.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |