|

|

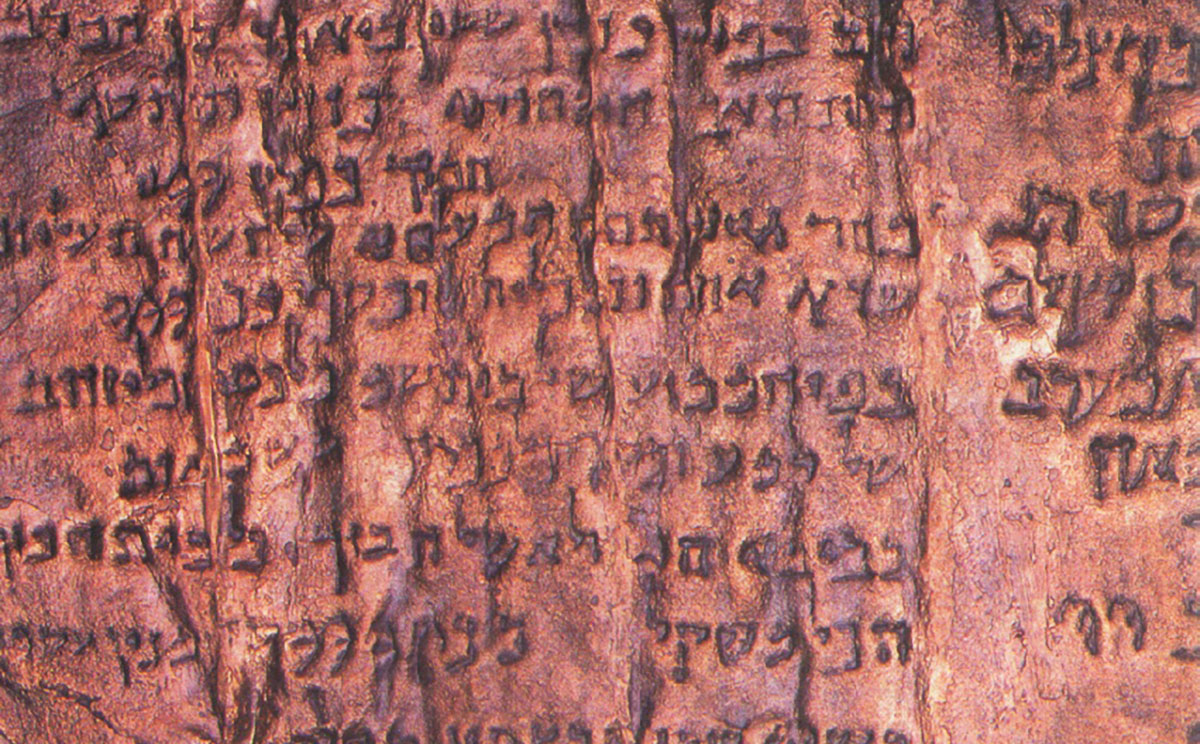

The Treasures of the Copper ScrollThis greatest of all imaginable treasures from the Dead Sea Scrolls probably never existed. Skeptoid Podcast #896  by Brian Dunning For ten years beginning in 1946, archaeologists carefully removed hundreds, and then thousands, of papyrus scrolls from the Qumran Caves in the Judean Desert, on the shores of the Dead Sea. Eventually some 15,000 scrolls and scroll fragments were catalogued, most of them papyrus, and some in parchment. Today we know them as the Dead Sea Scrolls, including the Biblical canons, extra-Biblical texts, and more, dating from some 400 years around the first century. But one particular scroll stands apart from the rest, in every way. It is neither papyrus nor parchment, but a single rolled up sheet of engraved copper — one scroll, out of fifteen thousand. It is not a Biblical canon, nor even a literary work of any kind. It is simply a list. It is a list of 64 places, and in each of those places, a fabulous treasure is described: its value in gold, silver, or other precious commodities; and where exactly to find it. They are the Treasures of the Copper Scroll, and today we're going to do our level Skeptoid best to determine whether or not they are — or have ever been — real. The scroll was corroded and far too delicate to unroll and bend it back flat for reading, so it was actually carefully sliced into 23 strips at Manchester University. The strips have since been photographed and cleaned up, and we can now read it. The dating of the scroll is not known precisely, and comes mainly from the context of other items it was found with. There's no way to directly date engraving on copper, so archaeologists look instead at where it was in the cave, behind other scrolls that can be dated — those others were mainly papyrus and parchment, and can be reliably radiocarbon dated. According to all available lines of evidence, estimates for the date of the Copper Scroll range from 25 to 135 CE, with most archaeologists putting them right about 70 CE. So the alleged treasures would have been hidden prior to that date, so probably sometime early in the first century. No indication in the Copper Scroll is given for what the source of these treasures might have been — or for who might have hidden them or why — but the only realistic source would have been the First or Second Temple of Jerusalem, where almost all regional wealth was concentrated through donations and tithes. One question immediately comes to mind. And the answer is no, none of these treasures has ever been found, at least not that has made it into any known record. One possible reason for this is that the instructions are a bit vague; it's like they're all missing some crucial piece of context. (This probably helps answer your next question, which is whether you can go and find some yourself.) Here is an example entry:

These few locations describe a total of 62 talents of silver. And when we calculate what that comes out to, we hit our first head scratcher. A talent is not an exact measurement; many cultures had various units of weight called talents and they all changed over time; there was little standardization. The units referenced most in the Bible are regarded as being roughly 35 kg or 75 lbs. Those 62 talents would be 2,170 kg of silver — more than two tons worth. That's a crazy, insane amount of silver, and this is just one entry from the scroll. Most of them are amounts in that range, and many of them are not silver, but gold. Two tons is not an implausible amount for men to move and bury, and whether it's plausible that any person knowing about it kept it a secret and never went back and took it is another matter. But if we want to stick to verifiable facts, we can at least look at known quantities, like the amounts of silver and gold referenced compared to what actually existed at the time. If you've heard me discuss legendary treasures on Skeptoid before, this is one thing you know I always like to look at; because one thing we often find in such cases is that it's often not possible for such treasures to have ever existed in the first place. So let's start with this. When you add up all the entries, the Treasures of the Copper Scroll total as follows:

So, clearly, gold is the bulk of the weight. So we'll focus on the gold. Can we figure out how much gold existed in the Mediterranean at the dawn of the first century? We'll start with some general background on gold in the Mediterranean at that time. Most of the gold yet mined in the world was in China; the second biggest source was Egypt. There were myriad smaller sources: Britain, Spain, India, Arabia, Eastern Europe, and others. Mining technology was in its infancy; milling and refining had to be done by hand, and without the benefit of chemicals. Let's have a look at the Chinese gold. Until about 1000 BCE, jade and bronze had been the valuable materials in China, but during the Zhou and Han dynasties which took us up to the first century, gold mining became very popular. In China it was mostly placer mining, which was easy picking of nuggets and gold dust. By the time of the Copper Scroll, China's total gold production had been some 372 metric tons. Our next biggest source is Egypt. Egyptians had been mining gold for thousands of years by this time, but almost all actual production was from the most recent centuries. These were the historical eras in Egypt called the Ptolemaic and Kushitic periods. These mines were in Nubia and the eastern desert of Egypt, near the coast of the Red Sea, forming a minority of some 250 known Egyptian gold mining sites, a total which includes later expanded production during the Roman-Byzantine times. Archaeologists and geologists have surveyed these sites and been able to estimate the production from each based on how much ore was removed, the richness of that ore, and how much of the gold the ancient hand milling techniques could recover from the ore. Based on all available factors, the total amount of gold produced in ancient Egypt by the time of the Scroll was about 7 metric tons. That's right, 7 tons. Compared to 372 in China. The Egyptians had to mill ore by hand, where the Chinese were able to sift it out and pick it up. Production from all those other locations was even less. It began to grow enormously throughout Europe in subsequent centuries as the Romans began large scale mining, but that hadn't happened yet when the Copper Scroll was being engraved. So our next step is to find out how much of that Egyptian and Chinese gold was in the Mediterranean (meaning the rest of the Mediterranean region, outside of Egypt), and we have a very clever way of determining that — and it comes from coins. Most of the precious metal coins at the time were silver shekels, but when it comes to gold, the most predominant was the Roman Aureus coin, plenty of which survive to this day for study. This gold can be analyzed both isotopically and by the content of tracers such as platinum and palladium. When we've done this, we find that the Aureus was made almost entirely of Egyptian gold — with no hint of Chinese gold at all. The reason is that trade with China was still at very small levels. The subsequent centuries would see it grow by leaps and bounds, but in the first century, there simply wasn't very much Chinese gold in the Mediterranean yet. Other gold had been brought into the Mediterranean by Roman military conquests and trade throughout Europe, but it was very little of the total at that early date. The Aureus coins minted by the first century used that 7 tons of Egyptian gold as almost their sole source — and, even more restrictively, only that portion of Egypt's 7 tons that had been traded into the rest of the Mediterranean! We don't have a reliable number for this, but it's something less than 7 tons. Let us consider that number in comparison to the treasures described in the Scroll that were made of gold. One item in the list references 900 talents of gold:

900 talents would be over 31 metric tons — more than at least four times as much gold as existed in that part of the world. And that's a single line item out of 64. So we know for a fact, with little room for provisos or alternate interpretations, that this one line is false; and in fact that most of the document must be false. It is unquestionably false that many tons of gold were buried in or around Biblical lands by the first century. If nearly all of the gold from the entire Mediterranean had suddenly disappeared one day, turning merchants into beggars and emptying the coffers of every temple, one would expect some historical record of the loss. So we're left with two possibilities: The scroll is fictional and does not reference actual treasures, or the amounts are all very, very wrong. This problem was evident even to the very first translators of the Scroll, John Allegro and Józef Milik, both of whom wrote books about it, were very aware of the problem, and proposed solutions. Allegro's solution, made in his 1964 book The Treasure of the Copper Scroll, was that when the local Judeans said talent they actually meant the maneh, the next division down from the talent, and equal to one sixtieth of it. His justification for this?

So he just decided that was the explanation and rolled with it, simple as that. The Copper Scroll was in some crazy, loosey-goosey slang, never seen anywhere else in any other ancient text. For this episode I had to read a lot of all that's been written on the scroll, and I saw half a dozen other explanations for the impossibility of the amounts, and no two agreed. I agree with Allegro that there's one thing we can say for certain, but I disagree with him on what that is. My version — which nearly everyone agrees with — is that we have no idea who wrote the scroll or what its purpose could have been. Why was it written in copper, with permanence in mind, when it has no evident meaning? There are no consistent theories on this either. Beyond the simple fact that the treasures referred to were not and are not real, it is simply a mysterious ancient document, the meaning of which died with whoever hammered its inscriptions into the copper, and secreted it away into a cave for two thousand years.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |