|

|

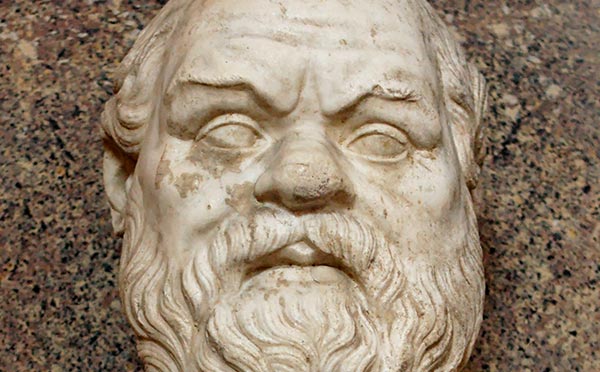

Asking the Socratic QuestionsSkeptoid Podcast #384  by Brian Dunning Of all the possible perspectives, beliefs, theories, ideologies, and conclusions in this world, which of them are beyond question? None of them. And neither should be any person who holds one of those positions. People believe all sorts of strange things, and even though they might be passionate about them, most will still admit that questioning their belief is an appropriate undertaking. Therefore, we — as scientific skeptics — have an available avenue by which we can always encourage believers in the strange to revisit their beliefs. Despite the fact that we may lack professional expertise in the subject at hand, we can still plant the seeds of an uprising of logic within the mind of the believer. One way to do this is through the application of Socratic questioning. Returning to our fake example guys used in the past, Starling and Bombo, we can illustrate this concept. Let us choose an example scenario. If Bombo has seen a UFO and believes that it was an alien spacecraft, it would likely be difficult for Starling to reason him out of the idea by offering alternative suggestions. People are often pretty stubborn when it comes to personal experiences that they've already interpreted for themselves; Bombo saw an alien spacecraft, and telling him it was the planet Venus would probably be a dead end. Indeed, even offering lines of logic for Bombo to follow on his own would probably be refused. So is there any effective way at all of getting someone to consider a different explanation? The answer is yes, and it involves getting Bombo to arrive at alternate explanations on his own. We're all far more prone to accept our own ideas than someone else's. Starling might well able to get Bombo to consider the idea that the UFO might not have been an alien spacecraft by employing Socratic questioning. Named (quite obviously) for Socrates — the ancient Greek philosopher (also quite obviously) — the Socratic questions are primarily teaching tools. Just as Bombo better accepts his own ideas, so do students of all types. Socratic questioning helps people to take a second, closer look at their own beliefs, and to apply critical thinking even when they least expect it. There are six commonly described categories of Socratic questions, and they're all good. You could familiarize yourself with any one of them, and you'd have a pretty good chance at changing Bombo's mind, or that of anyone else who has made a conclusion based on faulty logic. An adept at all six types of questions would be a formidable reformer of popular pseudoscience believers. Let's begin with the first type: 1. Questions of ClarificationIn order to engage Bombo's critical analysis of his own conclusion, we must first make certain that Bombo's conclusion is clear in his own mind. For example:

A great way to start is to make darn sure that Bombo understands the full force of what he's saying, which (assuming his belief is invalid) almost always raises a fatal weakness. Let's see if we can get him to clarify exactly what he's arguing:

That one question might be all it takes. Bombo might reflect for a moment, and then realize that all he can really say is that he saw something that he couldn't identify. Discussion over; Starling 1, Bombo 0; rationality 1, UFOlogy 0. However such an easy and early victory would not make this into much of an episode, so throughout, we're going to proceed as if nothing sways Bombo. Let us continue to clarify, and keep the focus on the invalid part of Bombo's claim.

Keep the crosshairs on the target. If Bombo is going to promote his claim, we want to make sure his only way out is to promote it very specifically and in no uncertain terms. Socratic questions of clarification are a great way to do this. You can even ask something like this:

Of course, in reality, Bombo is likely to blurt out at any time:

He might reasonably say that now, or at any time during the rest of these categories, and it's a perfectly natural response. But if or when he ever does say this, you've got a perfectly rational answer that even Bombo can't disagree with:

Bombo's the one making the outlandish claim; he's always going to agree that questions clarifying his claim are important. We can now move on to the assumptions Bombo has made that have allowed him to make his conclusion. 2. Questions that Probe AssumptionsRemember it's not all about Bombo's specific claim; it's about the faulty assumptions he has made about the world that give his claim a disguise of plausibility. So force Bombo to admit exactly what those assumptions are:

That's one facet of his claim. It has others, so let's look at those as well. One thing that characterizes many false claims is the existence of something that actually doesn't exist, like life force, ghosts, or other things that the claim depends on. Here we can force Bombo to re-examine his ability to have identified an alien spacecraft:

Of course he doesn't know, and of course he agrees it's an important question. So it's always interesting to see where he'll go from here. But, in my experience, sally forth he will. Push him harder.

Remember, when you're putting Bombo in a corner, any direction you push him is going to put him further into the corner (insisting his assumptions be immune to question) or you're successfully getting him to back down (admitting his assumptions should be considered open questions). Next let's see how he got to the conclusion he did. 3. Questions that Probe Reasons and EvidenceGet Bombo to take another look at the quality of his evidence and the reasons he found it convincing.

Of course there's no way he logically could have; but manage to, he did. If he's going to make a specific claim, then he must have some reasoning or evidence behind it that led him there. That reasoning must have allowed him to make this distinction:

Again, he's not going to know, so he either has to paint himself further into his corner, or he has to back off and admit the weakness of his position. Either way, the Socratic questions are making progress. Since the claim Bombo is making is a factual one, it's therefore testable. Most likely Bombo has not done any actual testing that led to his conclusion, and neither has anyone else; but every factual claim must be able to pass this question:

Next let's see if we can get him to question his preconceived notions. 4. Questions about Viewpoints or PerspectivesIs Bombo's fundamental viewpoint logically invalid?

This is not a straw man argument. What Bombo saw was unfamiliar, and he refused to allow the possibility that there might be Earthly things in the sky that he didn't recognize. He did not conclude:

He said:

So it's a fair question. It's also fair to see if he might be simply repeating pop tripe:

Or here's a good one. Get Bombo to honestly acknowledge what people from a different perspective would conclude about his observation:

5. Questions that Probe Implications and ConsequencesPseudoscientific claims often imply facts that, if they were true, would have tremendous impacts on our world. Think what a cure for cancer would do if it existed, or the implications if the government were found to have faked the moon landing. Encourage Bombo to see that his claim would have similar consequences; consequences that have so far failed to materialize:

Or:

Obviously, it would overturn much of what we think we know. Don't you think someone in science or government would have expressed an interest if so much of astrophysics were suddenly proven wrong? Or even the practical implications for the day-to-day guy on the street:

If Bombo's claim were true, the whole world would be in a huge fit. It's not; so what does Bombo have to conclude? 6. Questions about the QuestionAt any time, as mentioned previously, Bombo is likely to attack the questions themselves. Skeptical inquiry is, of course, the greatest enemy of falsehood. If that happens, ask something like this:

Or:

And finally, the most important question, that you probably will have already had to ask by now:

...and it really is the most important question. Nobody in the world wants to admit that their position is so tenuous that it can't withstand any questions, and so when put on the spot, they'll almost always agree that the questions which might lead to their position being found true should be asked. Once in a while you'll get:

...but even though he might say those words, he'll feel disingenuous even as they're coming out of his mouth. And he will reflect to himself, either now or later, that his assumptions and perspectives should be questioned. Because they should. Always. For everyone. On every subject. If your facts are right, you'll breeze through such questions. Everyone should welcome them, no matter what your perspective or your claim. In fact, I'll go out on a limb. If anyone feels that Socratic questioning is unfair to their particular field, one that the mainstream considers to be pseudoscience, email me. I'll be happy to do a specific episode addressing this, and I'll be happy to include your comments.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |