|

|

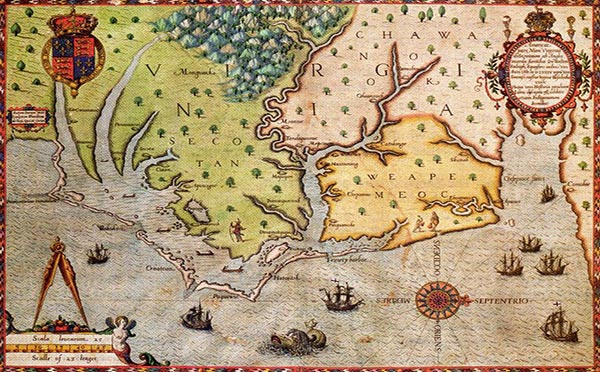

Finding the Lost Colony of RoanokeSkeptoid Podcast #245  by Brian Dunning When a relief party sent from England arrived at the Roanoke Colony on the East coast of the United States in 1590, they found the settlement neatly dismantled, and not a soul to be found. Some 115 men, women, and children had simply disappeared. The only clue was the name of a nearby island, Croatoan, carved into the trunk of a tree. And thus was launched one of history's great mysteries: The Lost Colony of Roanoke. Around 1580, the English mogul, explorer, and all-around famous guy Sir Walter Raleigh made a deal with Queen Elizabeth I to establish an English colony in America. He was given ten years to do it, and the deal was that they'd share in the riches they hoped would be found, and also create a base for English ships fighting Spain. Raleigh did not personally go, but his first expedition sailed in 1584 to find a good location. And find one they did: Roanoke Island, off of North Carolina. It's located inside the outer banks, a long string of narrow sand spit islands that shelter half the coast of North Carolina. Roanoke is fertile, defensible, well wooded, and offers substantial protected anchorage for ships. But Raleigh's expedition made some poor choices. Among the first things they did was to pick a fight with the local natives, charging them for some petty theft, burning their village, and beheading their chief. This was perhaps not the best way to establish friendly relations. Sir Francis Drake happened by during some of his pirating exploits, and finding the men in poor condition, he gave them a lift back to England. Strike 1 for the New World colony. What nobody knew was that Raleigh's second ship was already on its way. The two ships passed each other in the Atlantic, and the new group found an abandoned settlement. They returned to England, but left a small garrison of fifteen men on Roanoke to protect Raleigh's claim. The garrison was unaware of the bad diplomacy they'd inherited, and it should come as no surprise that they were never seen or heard from again. Strike 2 for the New World colony. Raleigh sent a third expedition to Roanoke in 1587, larger and better provisioned than the predecessors, commanded by Roanoke veteran John White, a prolific artist and cartographer who had originally been hired to document the colonization through his artwork. White re-established the Roanoke settlement, but failed to rebuild relations with the natives. They sometimes skirmished, and being vastly outnumbered and completely on their own, feared for their lives. As this was the first colony to include women and children, including White's daughter and her family, he was persuaded to return to England with a skeleton crew to ask Raleigh for help. With relocating the colony as an acknowledged possibility, White left instructions that if the colonists did choose to move in his absence, to carve their destination on a certain tree; and that if they were in trouble, to also carve a maltese cross. Arrived in England, White found that the war with Spain had complicated matters, and it was three long years before he was finally able to return with an armed party and the needed supplies. Unfortunately, there was nobody on Roanoke to receive them. The camp had been tidily dismantled; there had been no sudden massacre. White went to the tree and found a single carved word, Croatoan, and no carved cross. Wherever they'd gone, their departure appeared to have been orderly and planned, and they had not been in any immediate danger. Croatoan was a barrier island on the outer banks, now called Hatteras Island, about 35 nautical miles south of Roanoke. Today its flat dunes are covered with hurricane-hardened vacation homes. Sport fishing boats come and go, and kite boarders take advantage of its strong winds. But in the colonial days, it was one home of the Croatan natives, who were friendly to the English. It would seem to have been a logical destination, had food run out on Roanoke or if there had been some other cause to leave. Unfortunately, the weather had plans for John White that did not include allowing him to make the short hop to Croatoan to find his colony. A storm came in just as they arrived at Roanoke, and White's ship lost its main anchor. The combination of storm waves and wind, and a lost anchor, made it impossible to safely navigate the coastal islands and to land anywhere. The captain of the ship hired by White was anxious to get back to the more profitable business of privateering against Spain, and rather than his risk his vulnerable ship in a dangerous and fruitless coastal search, he opted to return to England. White arrived home empty handed. It was Strike 3, and nobody ever again heard of Sir Walter Raleigh's lost colony of Roanoke. It was the end of their story, and also the beginning of their legend. But colonies ultimately did take root in America, and it seems that those early colonists closest to Roanoke may have learned something of what became of them. The lost colony did eventually have neighbors, but they came some 25 years later and some 125 nautical miles of sailing to the north. It was 1607 when a more permanent colony was finally established in Virginia: Jamestown, named after King James, later famous for Captain John Smith, Pocahontas, and John Rolfe's tobacco. Jamestown struggled badly in its first years, and most of its colonists died from starvation or disease. They had few resources and never mounted an expedition to Croatoan to see what had become of their predecessors. Jamestown was in Powhatan native territory. Shortly before the Jamestown colonists had arrived, or at about the same time, the Powhatan had attacked and exterminated the Chesapeake (yes, the lovely Pocahontas was from a genocidal tribe). If any English or half-English had survived and been living with the Chesapeake, Powhatan killed them too. Relations between the English and the Powhatan were frosty, but the English were able to gain some small amount of information about what had become of the Roanoke colony. According to the Powhatan who were willing to talk, the original colonists had integrated into the mainland Carolina tribes to the west of Croatoan. There were a number of stories that supported this. John Smith was told there was a town where men dressed as he did, and another Englishman, William Strachey, wrote that he was told of:

Copper working was indeed known to the native Americans at that time. Further evidence for these stories was found later by Spanish agents, whose job it was to eliminate evidence of the English occupying and possessing America. They recovered a chart drawn by a Jamestown man, now known as the Zuniga Map, and sent it to Europe in 1608. The chart was inscribed with the place names mentioned by Smith and Strachey, but also mentions "four clothed men from Roonok." There is only one account of the Jamestown colonists actually encountering a person who appeared to be of English descent. He was seen in Powhatan territory in 1607, and was described as:

If this is a true account, and the witnesses were not mistaken in their observation and reporting, then this boy would have been born some seven years after John White found the deserted colony. It seems probable that the boy was a descendant of the Roanoke settlers who had either been spared by the Powhatan or was raised by them. Either way, it would be evidence that some of the Roanoke colonists did seek refuge to the north. Other accounts place the colonists south, either on Croatoan or on the Carolina coast. A century later, surveyor John Lawson wrote that the Hatteras natives on Croatoan:

The late Irish historian David Beers Quinn was probably our most knowledgeable scholar on the Roanoke colony. He devoted his career to the study of the colonization of America. Quinn's theory, developed after decades of studying many such accounts, is that the colonists abandoned Croatoan and separated into two groups. One group peacefully assimilated into the Carolina tribes to the west, and the other group went north to live with the friendly Chesapeake, reasoning that Virginia was the most likely place to which any future English colonists might come. We know that any who went north ultimately died, either naturally or at the hands of the Powhatan, but the fate of those who went to the Carolina mainland is less clear. Quinn's theory is the best available based on historical study, and needs only archaeological and genealogical evidence to back it up. Fortunately, both are forthcoming — sort of. There is archeological evidence that the colonists may have lived for a time on Croatoan, though it's not conclusive. Alongside artifacts of the Croatan natives, a gold ring was found bearing the family crest of the Kendall family, and there was a Master Kimball in the original Roanoke colony. However two English copper farthings were also found on Croatoan, but they were not produced until the 1670's, nearly a century too late to have belonged to anyone who was in the colonies at the time of Roanoke. Update: As eventually happens with nearly all artifacts of the colony promising to shed light, the gold ring was also recently found to be an anticlimax. —BD The DNA evidence supporting Quinn's theory may prove to be more revealing. Several different groups throughout the United States are currently analyzing DNA test results looking for clues to whether the colonists' genes survive today. Native populations at the time were quite small, and so it's more than likely that intermarriage would leave a substantial genetic footprint. In an article published in 2005 in the Journal of Genetic Genealogy, researcher Roberta Estes gave a thorough rundown of what's known so far, and unfortunately, the strongest point made is that there is insufficient data. When I think of the lost colony, I think of John White; of his many beautiful illustrations of native life in the Americas, and of the anguish he felt at sea having left his daughter at Roanoke for more than three years. I think of how helpless he must have felt, being unable to find ships to return. I think of how it must have been to find the word Croatoan carved into the tree, of his doubtless desperation to continue, and the frustration of having to return to England when he was so close to finding them. Where were Eleanor White, her husband, and White's infant granddaughter? Were they living safely with the Croatans, or had they succumbed to disease or starvation? He never knew, and we'll never know either. We may find better evidence of what happened to the colony as a whole, but the small personal tragedies will always remain unaccountable.

Cite this article:

©2025 Skeptoid Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |